|

|

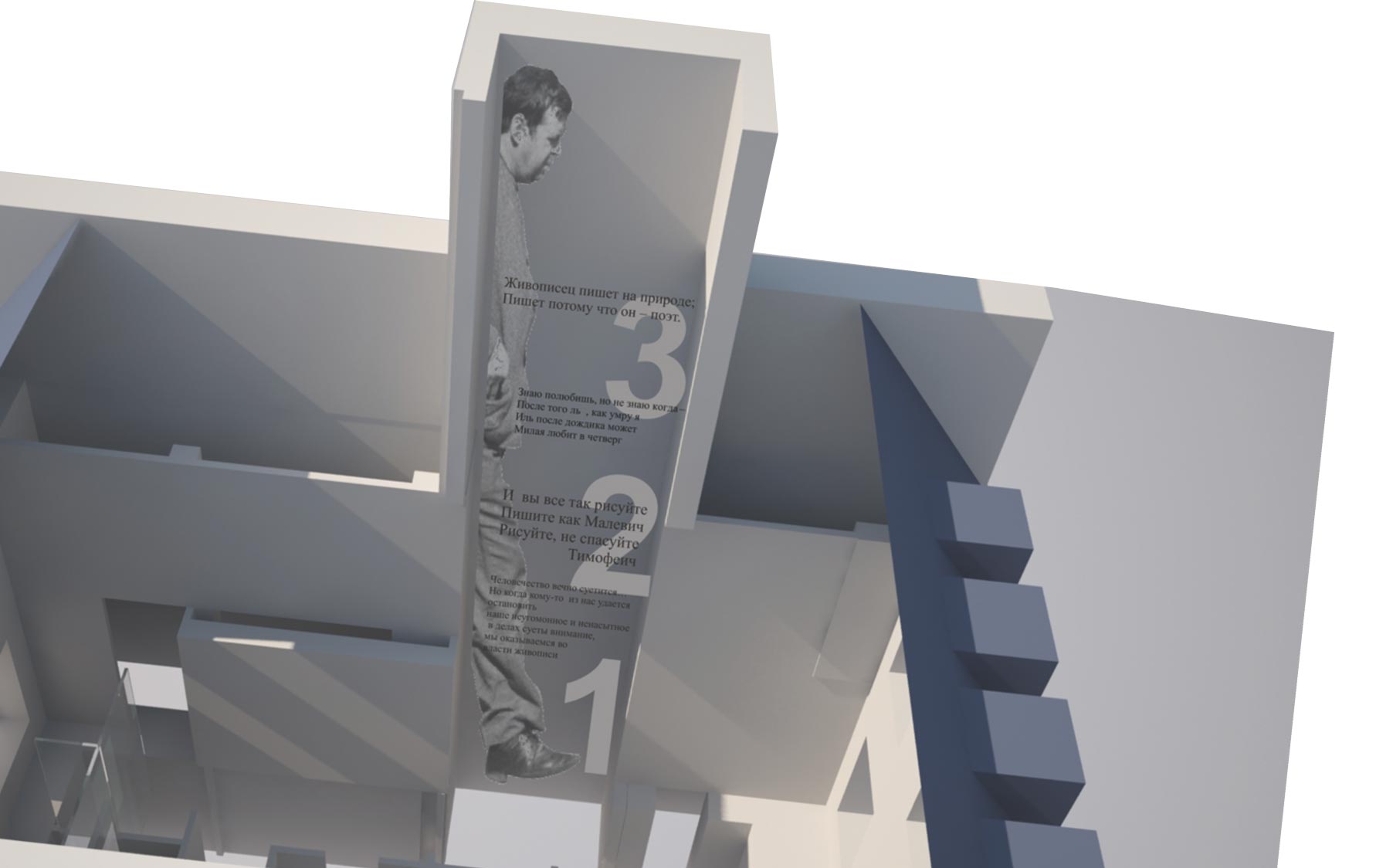

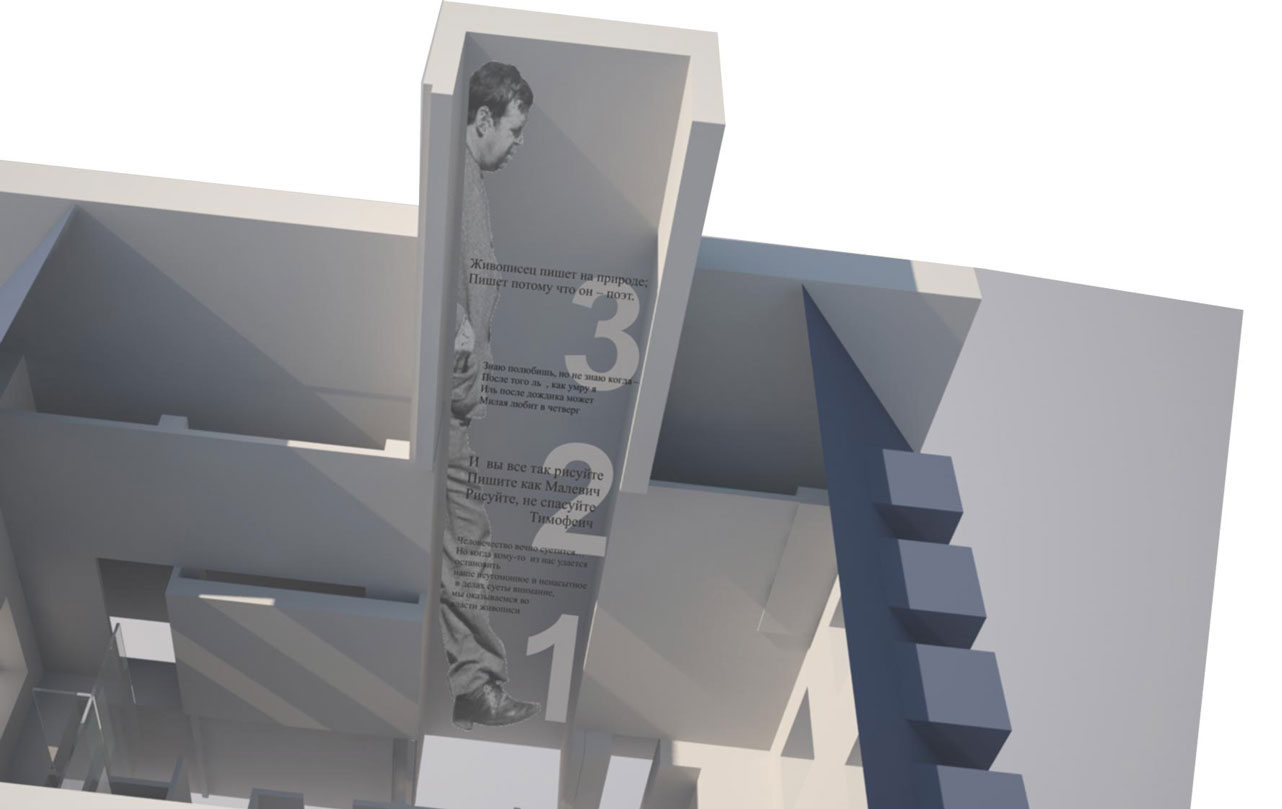

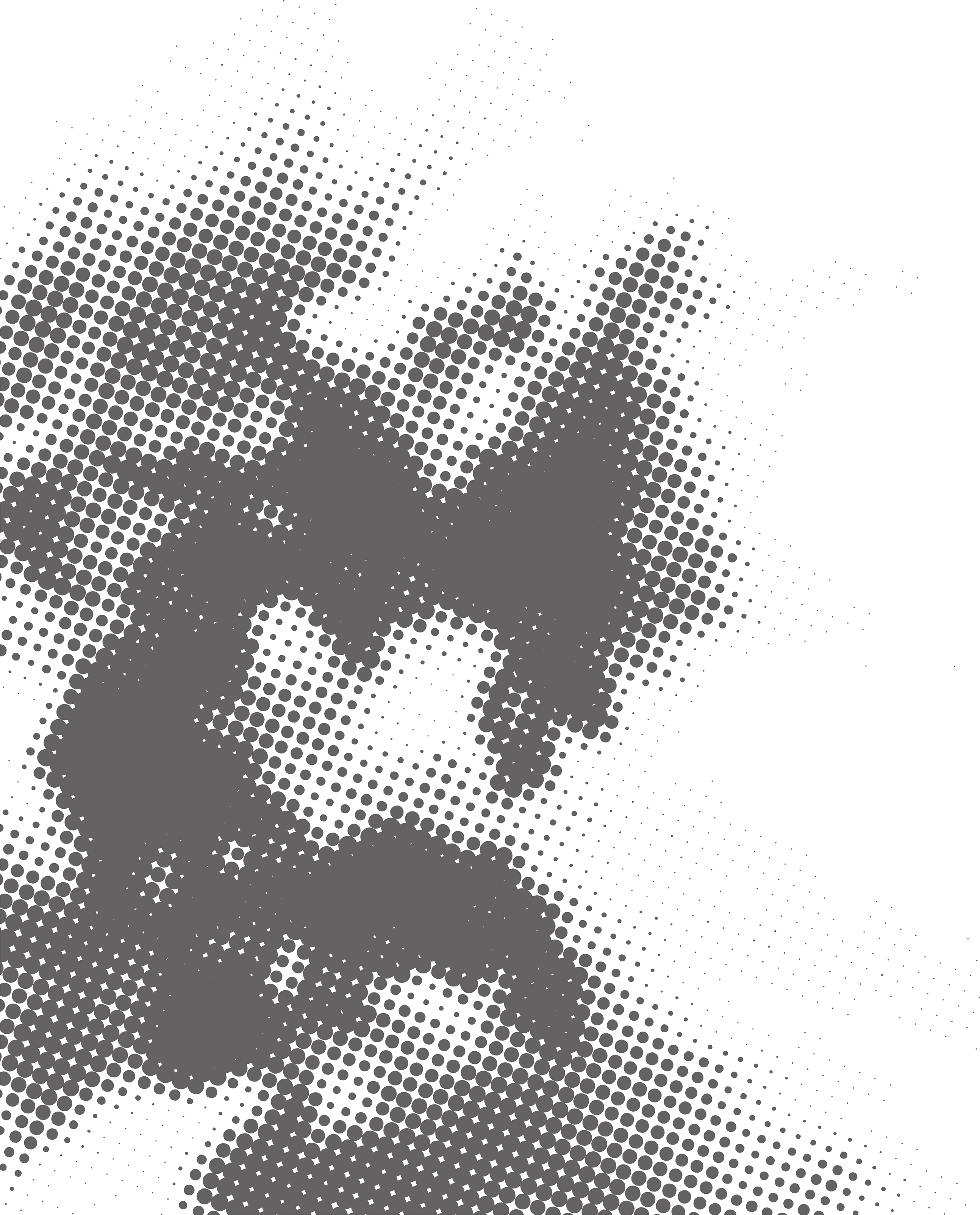

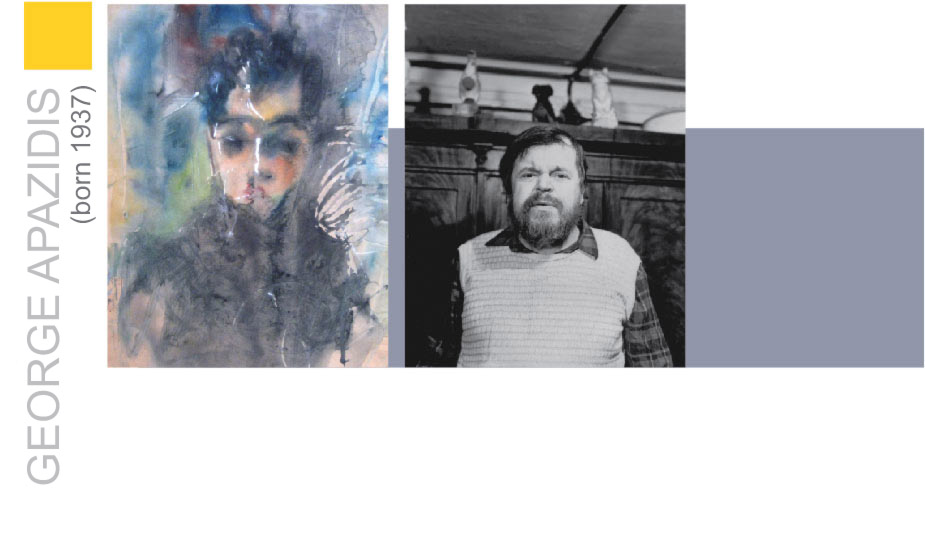

ALEXANDER RUMNEV (1899-1964)

Actor, ballet master, and teacher. In 1920-1933, A. Rumnev wasa member of the company of Alexander Tairov’s Moscow Chamber Theater. In 1940, he was invited to teach dance and choreography at the Mosfilm School of Acting. In 1944, he began to teach at the All-Soviet State Institute of Cinematography. Rumnev authored several monographs on the art of pantomime, including On Pantomime (Moscow, 1964) and Pantomime and Its Possibilities (Moscow, 1966; published posthumously).From his first meeting with Anatoly Zverev and until his death, Rumnev admired and supported Zverev, bringing him to the attention of many patrons and collectors. for more details |

|

“When you encounter a striking and original phenomenon in art, you want to understand, after the first shock passes, what impressed you and why?

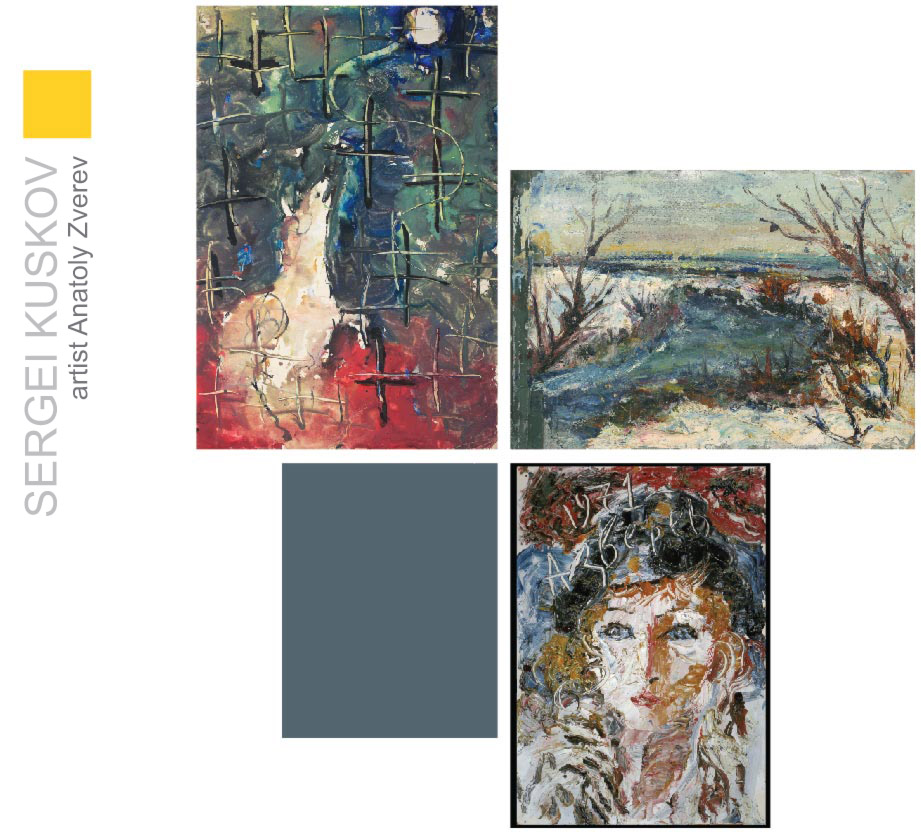

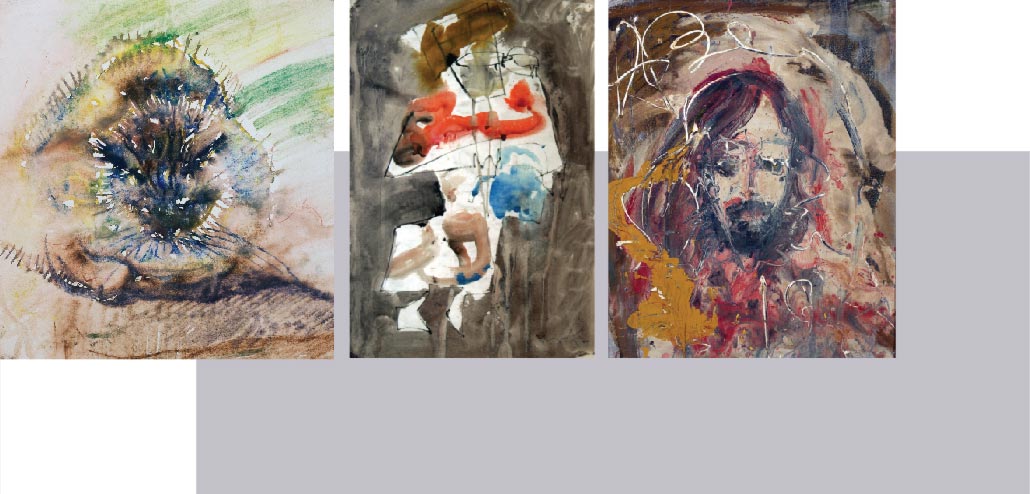

“The paintings of Anatoly Zverev, a young artist that is virtually unknown in his homeland yet that has long been attracting the attention of Western art lovers and collectors, belong to those unexpected and unique phenomena that strike us not only with their utmost mastery but also (and above all) with the originality of the world that the artist opens before us. As every striking personality, Zverev is difficult to classify in any painterly movement familiar to us. Let us simply say that his painting is objective, figural, and realistic in the best sense of the term. Zverev may be called an expressionist only in the sense in which Van Gogh, say, could be called an expressionist: in his work, he expresses, reveals and lays bare above all his own self. “This explains the rapidity and nervousness of his rhythms, which reflect the unstable mentality of a person that grew up in our uneasy times. The latter also explains Zverev’s striving to find beauty and harmony in the frightening world in which there still exist good people, gentle animals, shady trees and fragrant flowers. “The dynamism of Zverev’s art lies in the confrontation of the worrying and the comforting, the ugly and the beautiful. As viewers, we become witnesses to this tragic confrontation that takes place in the artist’s soul. At the same time, we become his accomplices, struck by his discovery that the world is better and more beautiful than we had thought before seeing Zverev’s art. This is not due, of course, to the artist embellishing the truth by straightening out his models’ noses, say. On the contrary, Zverev often amplifies and emphasizes ugliness. Nevertheless, he is able to see beauty in ugly, worrying and frightening things, transforming a fact of reality into a fact of art. “The power of Zverev’s art on the viewer may become easier to understand if we look at how he works. “As many great artists, Zverev is infantile. He has not lost his childlike spontaneity, immediacy of perception, and trustfulness. His soul and his eye have very quick reaction times. This requires the artist’s hand and its nerves and muscles to record impressions rapidly and precisely. Zverev’s hand responds to these demands with a febrile change of rhythms where tragic zigzags alternate with a refined lyricism of lines and where the frantic energy of brushstrokes, spots and drops can give way to a very tender and caressing contact between the brush and the canvas or paper. All of this is in such close harmony with his emotional states that, after a few minutes of work, the surface of the painting turns into documentary evidence of sorts of the artist’s spiritual state evoked by external impressions. The paper or canvas resembles a cardiogram that reflects the process of psychic exhibitionism. At the same time, the most trivial impression becomes captivating and joyous thanks to an unexpected perspective, a shift of proportions, deformations, unusual color relations, and, most importantly, a faster pulse. Empty dishes, toilets, stray cats, children with TB, alcoholics and prostitutes – this world of the city outskirts becomes no less beautiful and captivating than flowers and trees or swans and gazelles that Zverev admired at the zoo. The fact of reality is transformed into a fact of art with such energy, such conviction and such mastery that it cannot help but move, inspire and overwhelm the viewer. “Perhaps it is still too early to speak about different manners or ‘periods’ in Zverev’s art. Nevertheless, they clearly exist and are well known to his collectors. Such periods are numerous, for Zverev’s painterly manner changes frequently and radically. Each period of his would assure fame and fortune to any less talented artist. Yet Zverev is a squanderer. He finds and abandons, finds again and then changes his style and technique once more without regret, forgetting about his earlier acquisitions and not worrying that his riches may be depleted one day… Yet they are inexhaustible. Moreover, despite his different techniques and means of expression, he always remains himself: you can always recognize his artworks, as they reflect, during all his periods, the purity of his soul and its unique and inimitable poetic nature.” |

|

|

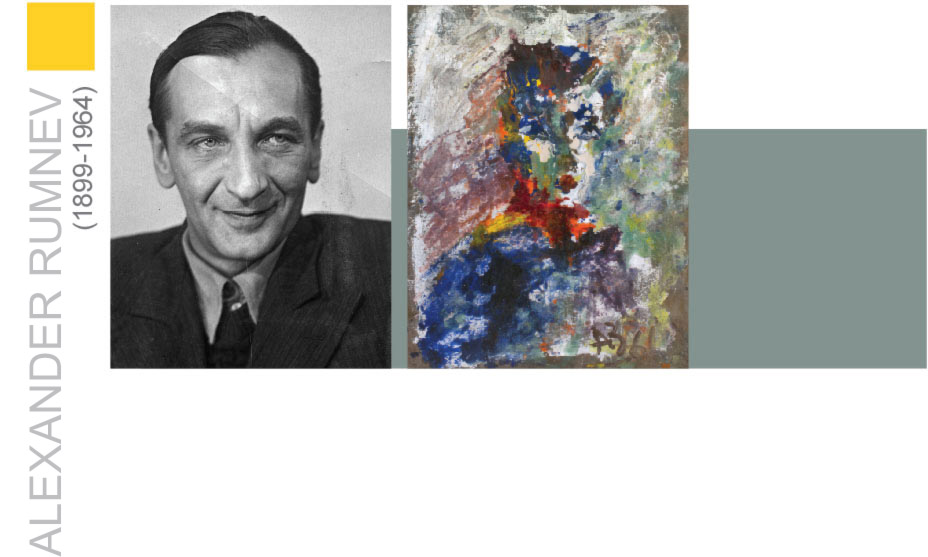

GEORGE COSTAKIS (1913- 1990)

A prominent collector and patron, Costakis gathered one of the biggest collections of Russian avant-garde and Soviet underground art. In 1977, he donated a major part of his collection to the Tretyakov Gallery before emigrating to Greece. Costakis was one of the first to actively support A. Zverev in the 1950s by buying and promoting his work. for more details |

|

A prominent collector and patron, Costakis gathered one of the biggest collections of Russian avant-garde and Soviet underground art. In 1977, he donated a major part of his collection to the Tretyakov Gallery before emigrating to Greece. Costakis was one of the first to actively support A. Zverev in the 1950s by buying and promoting his work.

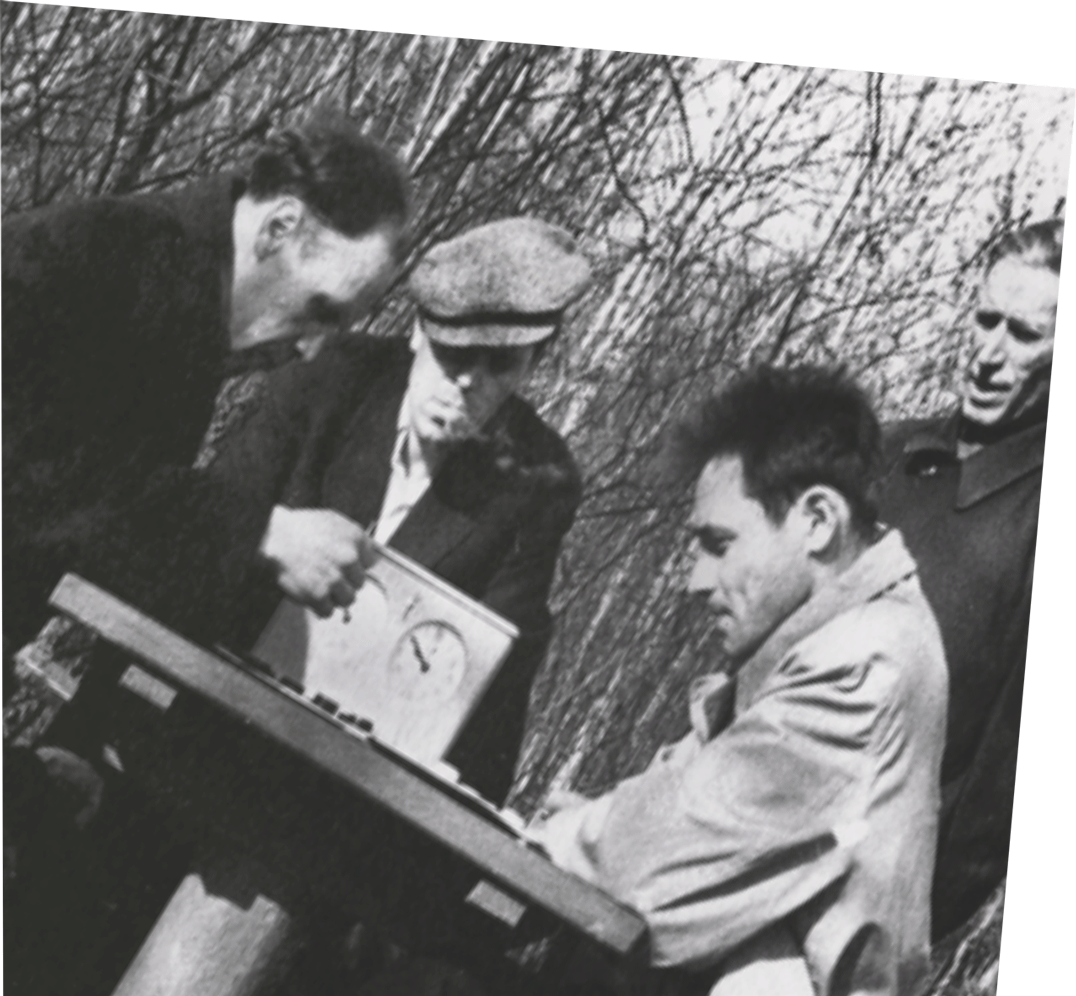

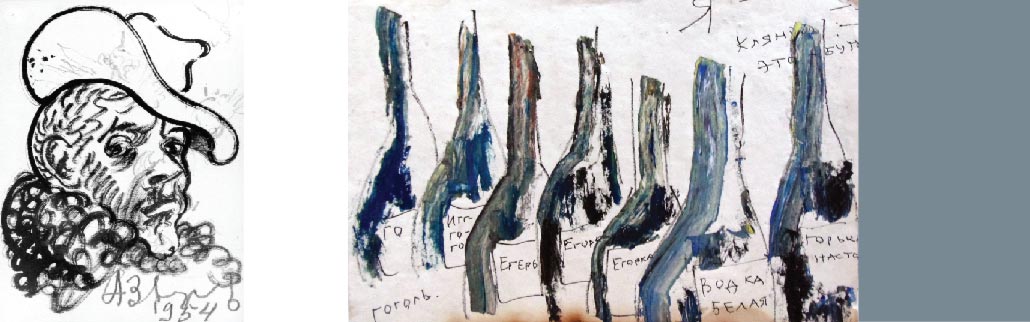

“I was introduced to Anatoly Zverev in 1954 by the composer Andrei Volkonsky, who brought me a large number of his drawings and watercolors. My interest in him began at that time and gradually evolved into friendship. MOMA Director René d’Harnoncourt and former MOMA Director Alfred Barr, who visited me in 1957, expressed the greatest esteem for Zverev’s work, singling him out among the young artists of the post-Stalinist period whose works were exhibited at my place. They purchased several works of his for the museum at the time. “Zverev did not get a formal artistic education. He entered the Arts Vocational School in Memory of 1905 yet was expelled several months later for not respecting the rules. His ‘fault’ consisted of arguing with teachers and refusing to change the lines on his drawings and alter the composition, colors and hues. He once had the nerve to say quite unabashedly before the entire class that teachers’ powers should be limited. ‘The teacher,’ he said, ‘must keep the classroom in good order, supply the students with paints, sharpen the pencils, and nothing else.’ For this he was expelled from the school. “Zverev’s early works, made in 1953, were executed on small pieces of ordinary cardboard in the style of classical Russian landscapes. In these black & white drawings of his early period, one senses a ‘raw nerve’. Although they were not imitations of Van Gogh, there is something very close to the spirit of the Dutch painter. Zverev was also prone to schizophrenia, and this may have made the two artists resemble each other. Zverev’s hearing was not affected in any way, yet he managed to break his fingers several times in fairly strange circumstances. Nevertheless, the fingers of his right hand were never affected. “I have the impression that Zverev always carried a pencil and paper with him, even when he went to bed. Any artist, whether living or dead, would be envious of his output. When his creative genius was at its height, his artworks, according to certain Western critics, were comparable only to the work of Matisse or Picasso. I usually classified his gouaches and watercolors of 1957 as his ‘marble period’. This was a period when Zverev was not particularly interested in ‘pure’ colors. He mixed watercolors not on a palette but on a plate where the paints, combining with each other, produced an attractive surface resembling marble. There were no pure red, blue or yellow colors at all: only a brilliant collection of gemstones that emerged from the artist’s spontaneous brushstrokes. An alternative was a huge metal basin in which Zverev boiled water and a brush that constantly floated in it: the brush was dipped in different layers of gouache in turn. The speed of brushstrokes constantly alternated, recalling drumsticks in the hands of a drummer. Drops of gouache flew in all directions, covering the walls. One had to erect plywood screens on three sides of the table. When the gouache dried and the image of the model could be made out on the portrait, it was difficult to imagine that the portrait had been made in such a way. Along with representative art, Zverev began to take an interest in abstraction. This period continued during all of 1958. Subsequently, each drawing became a search for the new expression of forms. It seemed as if Zverev was unable to find satisfaction: he never repeated himself when looking for new paths in art. This period continued during all of 1958. Subsequently, each drawing became a search for the new expression of forms. It seemed as if Zverev was unable to find satisfaction: he never repeated himself when looking for new paths in art. “During many different periods of his work, he employed a three-color technique: using white paper and three colors, he made romantic still lifes and portraits and drew tree trunks. ‘Even if he doesn’t have any paints at all, a real artist should be able to draw with earth or clay,’ often said Zverev. With his evident affinity for expressionism, he adopted the motto, ‘Anarchy is the mother of order.’ This order was always present in his work. The white sheet or canvas did not frighten Zverev. He looked at them like a musician looking at his instrument – e.g., a cello. Zverev’s bow was a big brush that he constantly used. When he was working with oil or gouache, it seemed as if he was playing effortlessly: he never corrected anything. As to his drawings, I would say that Zverev never worked like ordinary graphic artists. He depicted everything around him. Zverev drew a lot, working everywhere he could – in the subway, in the suburban train and in the tram. He even took his notepad to the cinema and sketched before the beginning of the film. His well-known trips to the zoo with his numerous notepads, in which he drew animals and birds, may well have represented the zenith of his work. “There one could compare Zverev’s sharp eye with a camera lens with the only difference that one has to change the film in a camera, while Zverev’s supply was inexhaustible. I was lucky enough to witness two such sessions (for lack of a better word). He made 6-8 sketches of each animal or bird from different perspectives. Anatoly drew animals with his fingertips dipped in India ink, using both hands. Deer, gazelles and other animals emerged from the shaky strokes of his fingers on the paper; the animals seemed to be alive. When he worked with watercolors, he used one big brush, as I have already mentioned. Working with gouache, he generously dipped the brush in water. Interestingly enough, when Zverev worked with oil, he also used one big brush that he never cleaned with turpentine or any other solvent. After squeezing the paint onto the palette, he freely took the colors he needed, one after the other, constantly turning the brush over and applying the paint onto the canvas. Nevertheless, the paints on the palette remained pure and did not mix. I asked Zverev how he managed to do it. ‘It’s very simple,’ he said. ‘A big brush has more hairs – a lot more than several medium brushes taken together. Yet you must know how to use a single brush. Beginning with a small corner of the brush, you must carefully dip a few hairs into the paint you need and then apply it to the parts of the canvas where this paint is required for the composition. After you apply this paint to different parts of the canvas, virtually none of it remains on the brush, which becomes dry. Then I turn the brush over and use the next color, dipping the brush hairs that are still fairly clean into it, and apply this color where required. The next color can be applied to the canvas with the side of the brush that has been used previously. An almost dry brush gives a different shade to a pure color. Then I find a place on the canvas where I need this shade. In this way, my brush becomes a palette on which the paints mix spontaneously, creating a range of soft colors. To use this technique, it is very important to apply the paints in the right order. In such spontaneous painting, you can work with only one brush,’ added Zverev. ‘Imagine a soldier that has several guns instead of a single machine-gun and that he must constantly reload them.’ “One is particularly struck by the optical vision in Zverev’s spontaneous works. In Peredelkino, where the poet Boris Pasternak is buried, there is a 15th-century church with an adjoining residential building where the patriarch once lived. One early spring, when the snow still lay on the ground, Zverev painted 6 canvases (100×80) on which he worked for ten hours. Zverev painted different spots on the canvas without a pause. About an hour passed. I looked closely at the canvas where there was nothing that resembled a church. An abstract drawing stood on the easel with a chaotic accumulation of spots of different colors. A few minutes before signing the work, Zverev began to make a church with the other side of the brush. He made three spots stand out and then gave the other spots the onion-shaped form of a dome. There appeared the outline of the church and then, God knows how, trees in the church courtyard and melting snow. The pink walls of the church glimmered. While I stood with my mouth open, Zverev depicted so well the colors of the sky, the melting snow and the church walls on these six canvases that even the inexperienced viewer can effortlessly tell at what time of day each of the pictures was painted. “Without a doubt, Zverev is a unique phenomenon. Moscow and Leningrad artists regard him particularly highly and say, ‘When the Lord anointed us artists, He poured the cup out on Tolya’s head.’ “As an individual, Zverev had ‘his head in the clouds’. For many years, this wonderful poet and artist gave his paintings to anyone that liked them. Always poorly dressed in a suit that did not fit him (someone had given it to him), he resembled a Parisian clochard. He did not like new and elegant clothing. Every time I bought him a new suit or coat abroad, he immediately went and sold it. At first sight, Zverev did not look his age. When he was 20-25 years old, he could spend hours kicking around a can with my 10-year-old son. At the same time, when he spoke with other artists, Zverev astounded them with his deep intellect and innate wisdom. I once left Zverev and Falk alone for a few hours, as I had to go away on urgent business. Although I never found out what they had talked about, Falk told me when I accompanied him to his place, ‘You know, Costakis, I esteem Zverev as an artist, yet, after speaking with him, I realized that his philosophical cast of mind is a lot higher than his great artistic talent. I was astounded by his intelligence.’ “It was a great pleasure to be Zverev’s friend, although it wasn’t always easy. Nevertheless, our friendship endured thanks to his honesty and tact for many years until my departure to the West.” |

|

|

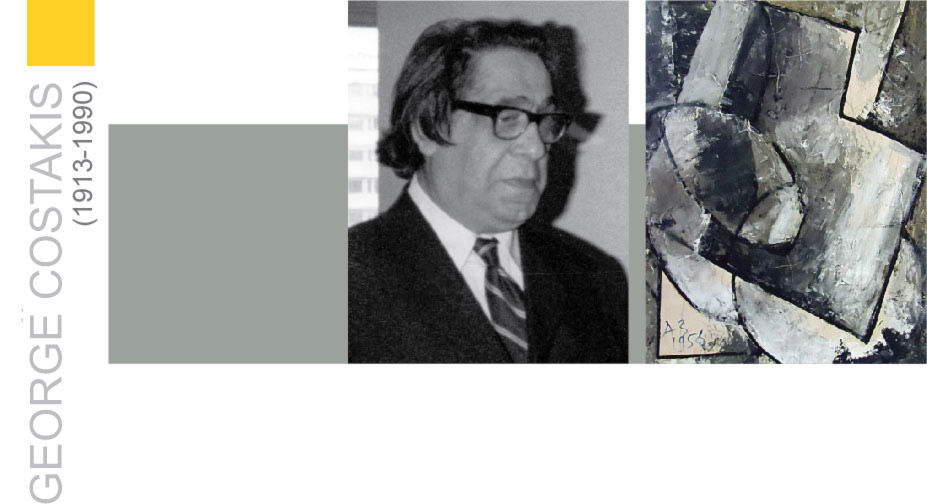

IGOR MARKEVITCH (1912-1983)

A French conductor and composer, Markevitch was born in Kiev, yet two years later his family moved to Paris. His talent as a performer and composer became apparent at an early age (at the age of 12, he made his solo debut at Covent Garden). He gained renown as one of the best performers of the Russian classical repertoire. All his life, he maintained close ties with Russian culture (he participated in Diaghilev’s Russian Ballets and was married to Nijinsky’s daughter). From the mid-1950s on, Igor Markevitch actively toured the USSR, where he met George Costakis and, thanks to him, Zverev. From the first encounter, he became a great admirer and promoter of Zverev’s work. In 1966, he organized Zverev’s first (and only lifetime) solo show in Paris at the Galerie Motte. for more details |

|

A French conductor and composer, Markevitch was born in Kiev, yet two years later his family moved to Paris. His talent as a performer and composer became apparent at an early age (at the age of 12, he made his solo debut at Covent Garden). He gained renown as one of the best performers of the Russian classical repertoire. All his life, he maintained close ties with Russian culture (he participated in Diaghilev’s Russian Ballets and was married to Nijinsky’s daughter).

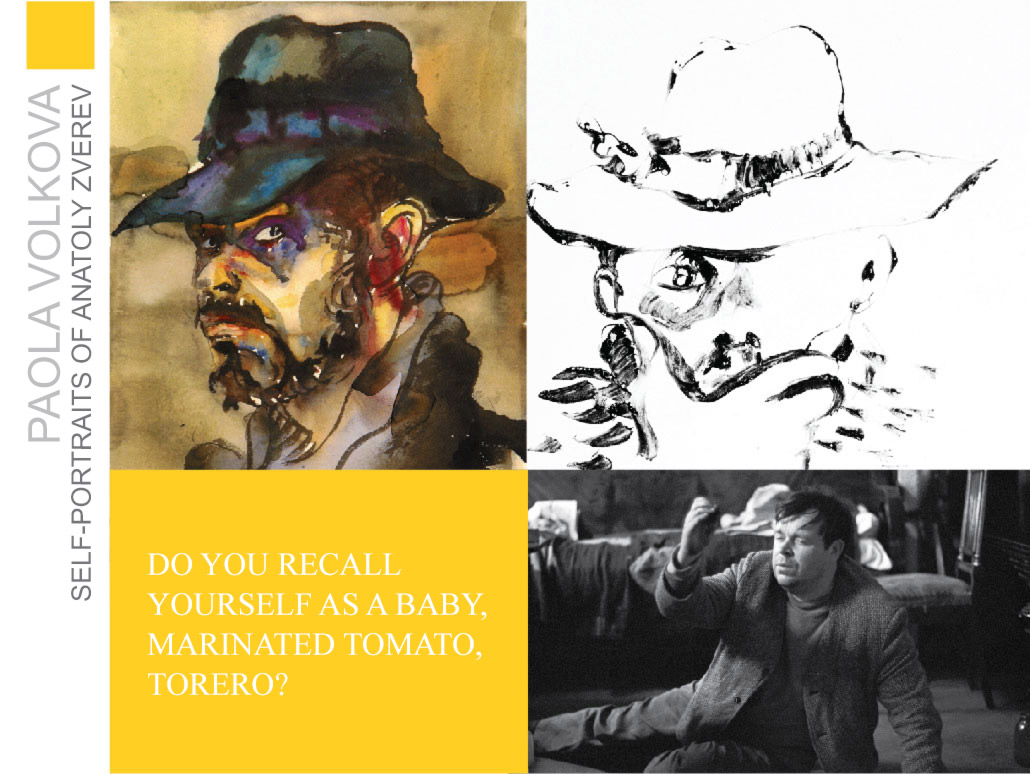

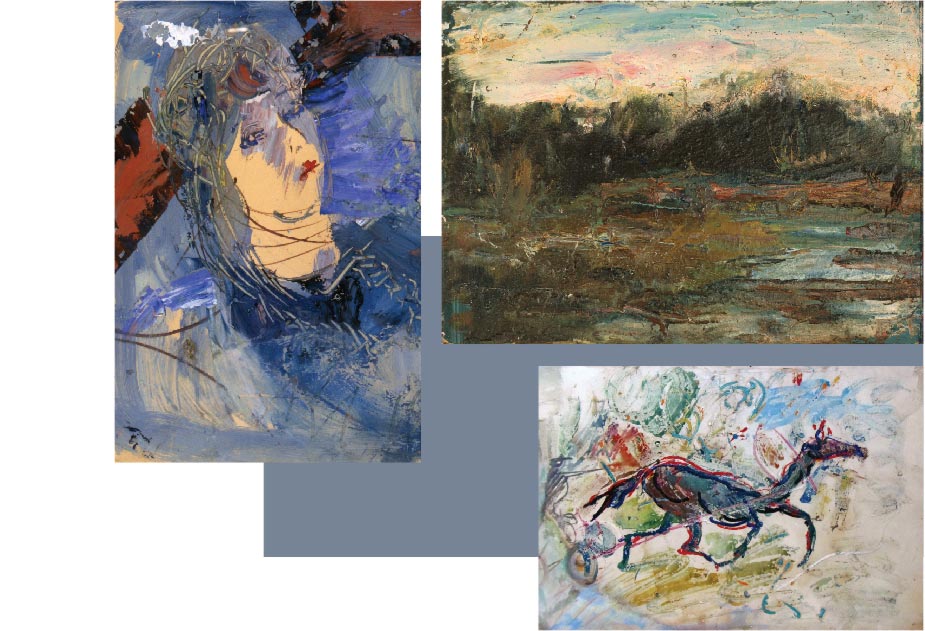

From the mid-1950s on, Igor Markevitch actively toured the USSR, where he met George Costakis and, thanks to him, Zverev. From the first encounter, he became a great admirer and promoter of Zverev’s work. In 1966, he organized Zverev’s first (and only lifetime) solo show in Paris at the Galerie Motte. “Presenting Zverev’s work in Paris, Marguerite Motte and I hope that it will be quite useful for the viewer to get acquainted with art movements that are still unknown in the West and that I got to know during my voyages in the USSR. Is not such an exhibition a reflection of the contemporary revival of painting, literature and music in the East after the appearance of new people that abound with tenderness and do not conceal their weaknesses? “Anatoly Zverev is little known even in his native country, as he is an elusive and difficult person that remains a riddle for even his closest friends. His admirers have told me about their first meeting with the pale and thin young man who was dressed in a sheepskin coat that was too big for him and different shoes yet who gave them his paintings ‘whose price they couldn’t have ever paid’. From this first encounter, they, just like the Western connoisseurs that had already seen his work, had no more doubts that they were dealing with an amazingly talented artist who was apparently destined to become one of the greatest artists of our time. “This exhibit introduces him to us as a portraitist and landscapist that paints with gouache, oil and watercolor. A book of his drawings shall soon be published, followed by his woodcuts and etchings. One can only marvel at the apparent carelessness with which the materials are used: gouache is sometimes mixed with watercolor, and oil is applied to cardboard and even poster paper. Zverev uses anything that he finds at hand. I have seen how he finished painting a bough of lilac with wonderful touches of cottage cheese. When someone expressed concern with the use of such a short-lived material and the possible appearance of mould, Zverev calmly replied, ‘Who says that the painting wouldn’t become better as a result?’ “We have decided to present a considerable number of Zverev’s self-portraits, which are one of the most distinctive aspects of his work. Only Van Gogh’s self-portraits, in my opinion, show such a determined search for the essence of man through the study of one’s own self – a search that is clearly mixed with narcissism in Zverev’s case. “Let’s turn to the position of such an artist in contemporary art. Zverev is a ‘phenomenon’ – the phenomenon of a person who reinvented, without realizing it, the history of contemporary art. “The Soviet artist Falk said about Zverev’s early work as a teenager: ‘It would be useless to teach him what everyone knows, because he knows what others don’t.’ Full of allusions to aestheticism, Zverev’s works have frayed new paths in contemporary painting in directions determined exclusively by his intuition. Starting with icons and the paintings of classical Russian artists that he saw in Moscow museums, Zverev then ‘passed through’ Moreau, Odilon Redon, Rouault, Dufy, Soutine, Kokoschka, Chagall, and Bacon, whom he had never seen, inventing himself companions for a few days or sometimes just for a few brushstrokes. In his drawings one sense the proximity of the East. Looking at a series of his horses drawn with India ink, Jean Cocteau admired this ‘Chinese Daumier’, considering Zverev’s work to be a bridge to Western art. “Nevertheless, Zverev’s inconstancy, which can be compared with Picasso’s inconstancy although Zverev’s work spans only 15 years or so, makes any classification premature. Yet one thing is clear: his work is lofty poetry that found itself in good hands and that is served by paints in all their power and beauty. “Zverev at work is worthy being filmed by Clouzot. He goes into a frenzy, and his hand, as if obeying orders, produces a wild stream of images that seem to outstrip thought. This breakdown of psychological barriers and rapidity of thinking make certain works of Zverev resemble encephalograms according to people that witness their genesis. Zverev can make up to a few hundred drawings or a couple dozen gouaches a day. This endless invention of painterly material allows him to effortlessly adopt and soon abandon countless ‘manners’ and invent and rapidly exhaust techniques. This impatient fecundity, this haste to express one’s ideas, and the confident stride of a wanderer on earth make it possible to compare Zverev to Hölderlin in painting. “Now a few words about Zverev as a human being. Comparing him with characters that are familiar to the Parisian public, I can say that he has something of François Villon, Jean Genet, Gavroche, Verlaine and even something (I don’t know precisely what) of a Franciscan monk. Yet Zverev reminds me above all of a common character of Russian literature that can be simply described by the word ‘ingenuous’ and whose immortal example is Platon Karatayev from War and Peace. It is hard to help a tramp, yet he inspires love, patience and paternal care from his friends, just as Van Gogh from Theo. He is crafty and meek like a little angel and mean when angry. His remarks seem to put everything in place and, at the same time, put everything in question. When I recently told him, hoping to please him, that Western critics have seen his paintings and found them wonderful, he simply replied, ‘They were very lucky to see what is good.’ I should add that his name means ‘wild’ in Russian, and Zverev is indeed a wild man. Such is the artist that we are presenting to French art lovers. Now let us let his works speak for themselves.” |

|

|

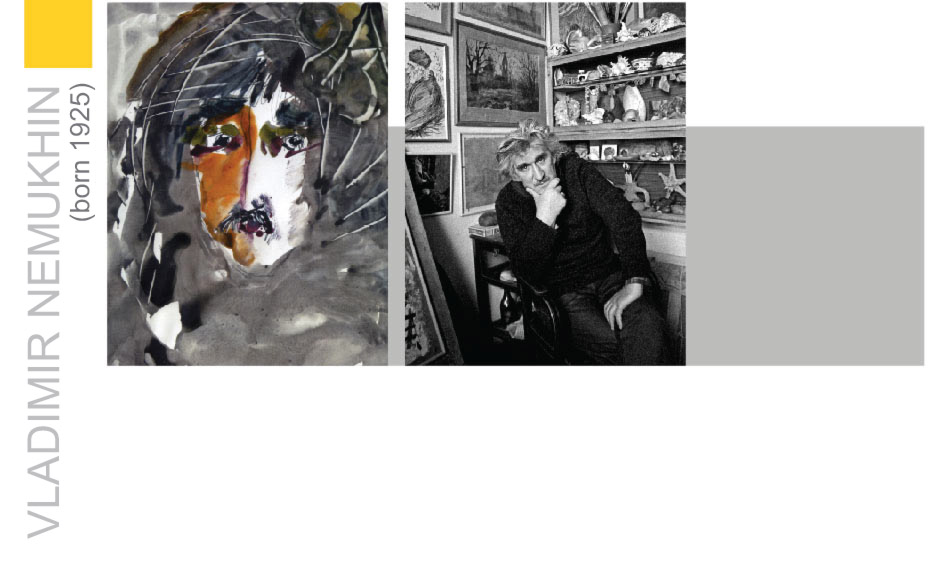

VLADIMIR NEMUKHIN (born 1925)

хArtist and member of the unofficial art movement, Nemukhin participated in the legendary

Bulldozer and Izmailovo Exhibits (1974). He experimented in the spirit of cubism and abstractionism. In the mid-1960s, Nemukhin actively developed the genre of the semi-abstract still-life with cards. Participated in over 50 exhibits in the USSR and abroad. He organized and curated A. Zverev’s only lifetime solo show in Moscow (City Committee of Graphic Artists, 1984). for more details |

|

Artist and member of the unofficial art movement, Nemukhin participated in the legendary Bulldozer and Izmailovo Exhibits (1974). He experimented in the spirit of cubism and abstractionism. In the mid-1960s, Nemukhin actively developed the genre of the semi-abstract still-life with cards. Participated in over 50 exhibits in the USSR and abroad. He organized and curated A. Zverev’s only lifetime solo show in Moscow (City Committee of Graphic Artists, 1984).

“How did I get to know Anatoly Zverev? It was back in the sixties. At that time, we artists found each other from scraps of information, and it was very interesting to see how different people painted and what they did. “As to us, we were abstractionists at the time. We were trying to make a name for ourselves. We were doing it every day and every minute, and figurativism wasn’t interesting for us anymore. If you could make something out on a painting – a nose or eyes, say – it meant that it wasn’t any good. “I first heard about Zverev in 1959. All kinds of rumors circulated about him, and I was curious to see his work. I finally saw it when I visited Costakis one day. I remember that it didn’t make a big impression on me, in part because I was overwhelmed by Malevich, about whom I was crazy, and I had never seen Popova or Kandinsky before, because all these museums were closed. In short, Zverev’s works seemed interesting yet did not captivate me. As to Costakis, he treated Zverev with awe as an outstanding artist and kept citing Falk that ‘each brushstroke of his was precious’. Costakis, naturally, had a deep feeling for Zverev, yet he nevertheless kept asking others about his talent, as if he was unable to assess it fully himself. “Costakis also loved Vladimir Yakovlev, who greatly impressed him, I believe. Why? “The thing is that Costakis secretly painted, too, and, when he emigrated to Greece, he painted everything that he had dreamt of in Moscow. I recall his words, ‘Collecting everyone, I stifled the genius in me’. And it may well have been true. So Yakovlev’s work seemed to have been closer and more understandable to him. He considered him to be a primitive artist, i.e., it was possible to imitate Yakovlev in some way. As to Zverev, it was totally impossible to imitate him, especially as Costakis collected Zverev’s early work, in which his genius was particularly evident. I believe that Costakis was not the only one to see this. Many artists saw it. Zverev’s work got high praise from Picasso. When Picasso’s friend, the French conductor Igor Markevitch, brought Zverev’s work from Moscow to Paris in 1965 and showed it to him, Picasso called Zverev a very talented artist. People often cite Picasso’s words that Zverev was ‘the best Russian draftsman’. This statement seems somewhat exaggerated and far-fetched to me. Picasso was mostly familiar with Russian avant-garde art, and so his assessment was not very objective. Nevertheless, as I said, this was naturally very high praise. “Zverev first visited us in Khimki-Khovrino, where Lidia Masterkova and I lived in a one-room apartment. It was in 1964, and I had already heard many incredible stories about Zverev’s bohemian life. I observed him carefully and, as I recall, initially found him to be even somewhat banal. He was wearing a clean white shirt, whereas I had expected to see a drunkard. On the contrary, he even looked quite decent. Nevertheless, the way he spoke, somewhat disconnectedly and aphoristically, already aroused my interest back then. However, his remarks did not make such a big impression on Lidia. She considered herself a great artist and did not listen to anything that contradicted her own opinions. Zverev probably noticed right away the modest atmosphere at our place and decided that it was not for him. He took a look around, got to know us in a way, and left. I subsequently met him several times at Costakis’ place, yet our first real meeting that led to a close friendship took place in 1968. “Masterkova and I had separated by that time, and I had moved to my studio. I was in a very bad state. I had suddenly found myself alone. I suffered and didn’t know what to do. One day, there was a knock at the door, and Zverev appeared. He had come alone. By that time, I had furnished the studio a bit, getting a table and a bench. I was happy to see Zverev. I had been in a state of virtual dementia, and Zverev’s visit immediately brought me out of it. Looking for solace and advice, I told him about my problems. He replied, ‘All your mishaps, old man, come from society. Society is making you depressed. Yet society is like a wall. You see, you’ve got a wall in front of you. Cover it with pictures. And it’ll recede.’ I recall liking his words a lot. Our friendship naturally began with a glass of vodka and subsequently continued for a very long time. “Speaking of Zverev’s work, it is interesting to hear how he assessed it himself. He often told me, ‘Old man, I was an artist until the sixties, because I painted for myself. After the sixties, I began to paint for society.’ “He particularly valued his tachist period. He used to say, ‘I, not Pollock, invented Tachisme.’ He had already abandoned pictural composition and adopted a different worldview. He painted with spots – big spots. I saw such works of his at Costakis’ and other places. He believed that Tachisme was the zenith of his work: ‘I painted, old man, with my blood and wouldn’t be able to do it again.’ “So far as I know, Zverev painted very differently in different homes. This sometimes turned into a real farce. As if trying to please his host for letting him spend the night, Zverev painted anything that he was asked, and all this social politesse greatly changed him as an artist. When he came to someone’s home, people would ask him, ‘Tolya, paint the dog. No, the cat. No, you with the dog and the cat. How about the bird? Paint yourself with the bird.’ He almost never painted on his own and always asked what to paint. I recall how he wanted to thank the doctor when he was at the hospital with a broken finger for the last time. He didn’t know what he should depict and asked the doctor to write down what he wanted. The doctor’s wishes were quite unexpected. He wrote, “ 1) An eagle, 2) A mountain, 3) Vacation at the country home, and 4) Something involving a car and a dog”. Tolya painted for him his wife and something resembling a social gathering under a pine tree on the Moscow River. “By the way, when I came up with the idea of making a Zverev exhibit, I was initially aghast: what a crazy idea! Why did I take it up? I was totally disheartened when I saw all these dogs, cats and so on. One got the impression that people simply told Zverev what to paint. As for him, he had never asked for this exhibit – he simply didn’t care. Only when we started gathering his works later, he tried to recall where they were. I had a few good works of his – they were really good – yet this wasn’t enough, of course. Naturally, there were a lot of works of his at Aseyeva’s place, yet, personally, I didn’t like them with the exception of a few outstanding drawings. The paintings that hung on the walls seemed too ‘artsy’, for the lack of a better word. I even found all these paintings, including Aseyeva’s portraits, a bit irritating. Aseyeva came out of the incredible bedlam of the twenties and suddenly turned into something powdered and saccharine. I recalled Zverev’s wonderful works at Costakis’, yet Costakis had emigrated to Greece and had seemingly taken everything along. I knew that many paintings had been destroyed during a fire at Zverev’s dacha yet, just in case, called his daughter Natasha up. She said that she did have Tolya’s works, and I went there to see them. When I saw them – even those that had been burnt – I heaved a sigh of relief. Yes, the exhibit was possible. I begged Zverev to behave properly during opening night: ‘After all, it’s your event. We’ll celebrate afterwards in the evening.’ “During the period when Zverev began to paint for society, changes also took place in his personal life. Although he had two wonderful children – a son and a daughter – he separated from his wife ‘Lusya #1’ and became a Moscow tramp. This is a story in its own right, as Zverev was a Moscow phenomenon, of course. He couldn’t have appeared in Leningrad or any other city. “He was incredibly obsessive, and people took advantage of his obsessiveness. And, if they had only known how obsessive he really was, they would have taken advantage of it even more. He had a particular obsession for material. This was an expression of simple greed that stemmed from his childhood due to his poverty. No matter how much paper you gave him, he would use it all up. This obsessiveness characterized all his behavior. He once asked me, ‘Old man, give me a big thick notebook. I want to write a novel.’ And, by 4 a.m., the novel was finished! He had written it in block letters. Filling up a whole 100-page notebook with them wasn’t easy. That’s how obsessive he was… Costakis himself was surprised when he asked Zverev to draw a series of illustrations to Apuleius, leaving him at his dacha with a pack of paper and a bottle of vodka. He later recounted, ‘When I returned in the evening, he had used all the paper up and was playing with the dog as if nothing had happened.’ “By the way, I should say a few words about his signature. He began writing ‘AZ’ (‘АЗ’ in Russian) on his drawings and paintings from the age of 15-16, and then, from 1954 on, signed everything, absolutely everything. That’s interesting. After all, he was such a disadvantaged artist… It was as if the hand of providence had made him sign everything. After all, young artists had different attitudes towards signing works. Many of them believed that it was unseemly or immodest in a way, yet he signed everything. “His ‘АЗ’ always seemed to be an organic part of the picture. His signature was often followed by the date. I recall how happy he was in 1983, because the digit ‘3’ could be simultaneously interpreted as the letter ‘З’. He took pleasure in this calligraphic signature, which almost resembled a Chinese stamp on his drawings. In my collection, I have seven versions of his signature, and I want to make a china dish with all of them. “Of course, he was greatly talented – incredibly talented! – from birth. He was an innate musician. I heard him play. He didn’t simply press the keys but played wonderfully. I recall how he sat down at a piano in one apartment, and I was simply astounded: I was listening to a real pianist. It was a remarkable moment! “In the same way, he was an outstanding painter and graphic artist. And what a sculptor he was! I saw his horses in one apartment. He made them out of clay, gray clay… I even wanted to ask the owners to let me cast the sculptures in bronze, but they were planning to emigrate, and I lost track of them. Yes, he was a wonderful sculptor – just as good as Paolo Troubetzkoy, say. Yet Troubetzkoy was a product of one time, and Zverev of another. “And he was an excellent checkers player. The famous Kopeyka said that, if it were not for Zverev’s art, he would have become a checkers champion. He attended the checkers club in Sokolniki, where people simply worshipped him. “And, of course, his incredible passion for football! He was an innate goalkeeper. And how he stood in the goal! He was totally bent on not letting the ball get past him. It gave him supreme pleasure – pure bliss! We attended football matches together. He was extremely passionate. We always took vodka or beer along. He never went to the stadium without them. He bought tickets to all the different stands at once. He bought up to twenty tickets at once. What for? To get away at once, if he had to. He had a real persecution mania, although it is true that we were being followed at the time. After all, we had already begun to engage in some bold dissident activities. He would suddenly decide that he was being followed and would drag me to another tribune – from the north to the south tribune, say. It was just terrible: he dragged me along like a cat or something. ‘You’re a liberal – you don’t understand anything. Don’t you see that they’re watching and following us?’ Or he would grab and take me to another street where he would immediately catch a taxi to cover his tracks. “One day, he took me out of the Pushkin Fine Arts Museum in this way. It was quite interesting. I proposed to him, ‘Let’s get over a hangover in a civilized manner today. Let’s go to the Pushkin Museum.’ He replied, ‘You know, you can buy hot dogs there. We’ll dine in the cafeteria. They sometimes serve beer. Let’s go.’ “And so we went there. The cafeteria was closed. We were going around the museum rooms, and I paused, probably for the first time ever, before the sculpture of the boy taking a thorn out of his foot in the Greek Room. I stood there and admired the sculpture. Suddenly, Zverev grabbed me and began to drag me out of the room. ‘Don’t you see? You’re crazy or what? Don’t you see that they’re following us! Fool! Liberal! They’ll arrest you if keep standing there! They’ll take you away, you <…>! Stop standing there, hear me?’ And, all in a huff, he grabbed me, and we left the room and continued on. “In a word, he was an eccentric. For example, he was terribly squeamish. Once I spent the night at his place in Sviblovo. On the way, we stopped at a drugstore, where he bought an enormous amount of baking soda. Zverev sprinkled it all over the apartment – on the table, the floor, the chest, the couch on which I was going to sleep, etc. He almost never ate at home. I recall that his mother left him an apple and two eggs for breakfast. He said, ‘Old man, you can eat that if you like. I don’t want it.’ “He often spent the night outside my door. I would come home and see him sleeping on a couple of newspapers there. This often took place in winter. He would come when I wasn’t at home. People had expelled him from somewhere. And so he lay down to sleep there or waited for me: ‘Old man, it’s me.’ I would ask him, ‘What are you doing? Is that possible?’ ‘What could I do, old man? No one took me in.’ “So there were a lot of destructive and difficult things in his life. Yet he never complained. Never. “Zverev got his arts education at the Tretyakov Gallery. He loved Russian art, even though he considered himself to be a disciple of Leonardo da Vinci. For him, the latter was omnipotent, as he was also a poet, an engineer, a sculptor, an architect, and a scholar. He couldn’t imagine anyone better, although that’s debatable, of course… “His opinions were very original and very exact. He once spoke with me about my work. I recall him telling me, ‘Old man, you know what? If you had not made your white works, you wouldn’t have ever attained salvation.’ He was right in a way. I subsequently tried to understand why he said so and tried to speak with him about his assessment. Yet it was useless to ask him about it. He didn’t like questions. If you insisted and kept asking him, he’d avoid the subject altogether. “He never spoke badly about artists – in part, because he simply didn’t have a need for it and took no interest in it. Yet, if he had a rival of sorts, it was Vladimir Yakovlev. Zverev was never indifferent to his work and reacted very aggressively to it. In contrast, Yakovlev liked Zverev a lot and always called him a fighter. When I showed Zverev drawings and paintings by different artists, he always reacted calmly. However, when I would speak of Yakovlev, he immediately became aggressive and began to give him marks. ‘F! F! F!’ ‘Why F?’ I would ask. ‘Let me show you another work of his.’ ‘OK, old man, C- and not an ounce more!’ There was something very complicated about it. When Zverev spoke about Yakovlev, he would say with his characteristic mockery, ‘Yes, of course, old man. He can do whatever he wants, because they all wear good coats.’ He said that after he had once seen Yakovlev’s parents, who wore coats with astrakhan fur collars. Zverev clearly considered that to be the epitome of wealth, behind which any artwork could hide. Just paint as you like! This was not humor – he always reminded me of these coats. In a word, he was quite sensitive about Yakovlev, as I recall quite well. “Zverev liked poetry, and his attitude towards it was quite unusual, too. For example, he didn’t like Pushkin, considering him to be an official poet, and he disliked everything official. In contrast, Lermontov was not an official poet. He told me that himself. For him, Lermontov was more romantic, should we say, and he made numerous works based on Lermontov. I once asked him, ‘Perhaps you should try to illustrate The Demon?’ He replied, ‘You know, Vrubel has already done it.’ He loved Vrubel and sometimes even compared himself to him. His favorite work, which he painted as a child, was a rose. ‘You know, old man,’ he said to me, ‘it was a wonderful rose, just like Vrubel’s.’ This rose was at Rumnev’s place. Although I have never seen it, I’m sure it wasn’t painted with oil. By the way, many people tried to get his oil paintings, yet I believe that Zverev was a pencil and a watercolor artist. He didn’t like oil. He always spoke pejoratively about it. He didn’t even use it at first – in particular, because he could afford watercolors, which were cheaper. He liked this material and had a feeling for it. “Was Zverev aware of his own worth? Yes, of course. And he was aware of his possibilities, too. He was an ace draftsman, and his talent was innate. Nevertheless, not all artists appreciated his work. After all, you have to be free to be able to appreciate others generously. For me, for example, freedom lies, above all, in the intellectual possibility of exercising it. I believe Zverev did not particularly strive for this. Perhaps it was alien to him. “Strange though it may seem, Zverev’s talent was in many ways contradictory to him. He remains a riddle to me – a very complicated riddle. However, Zverev’s biography can appear salutary if one looks at it from the standpoint of Christianity, which is very apparent in his work. It is simply surprising: such a life – and such purity in art. His work may be called divine. This is true of all great artists. This was true of Vladimir Weisberg, and it is true of Vladimir Yakovlev. Yet all these people suffer immensely. “During the period of my first meetings with Zverev, he fell in love with Oksana, the widow of the poet Nikolai Aseyev. For me, it was very interesting to see her, as she was such a legendary woman from such a historic period. He always touchingly bought her flowers and literally showered her with letters. Once he came to spend the night at my place, bringing a pile of newspapers with him. He spread them out on the floor, and they rustled all night as if a hedgehog was walking over them. In the morning, while I was still asleep, he began to write an enormous number of letters with only a few words in each. He immediately sealed them in envelopes and asked me, ‘Old man, help me stuff all of them into the postbox!’ All these letters were addressed to Aseyeva. We took them to Sadovaya and Malaya Bronnaya Streets. The next day, we started all over again. I said, “Old man, let’s write one long letter. It’s awfully difficult sending so many letters.’ Zverev only replied, ‘You don’t understand anything in such matters!’ “One day, I finally saw her. She came to me with Tolya and, from the start, made the impression of a very nice, exuberant and unaffected person. It was December, as I recall. She was wearing an orange sheepskin coat and had a big black eye! She immediately began to complain that he had hit her, while he accused her of infidelity. As it turned out, her doctor had provoked his jealousy. The doctor began to examine Oksana when she was ill, and Zverev told him, pointing at the stethoscope, ‘Use that rubber thing of yours and don’t dare touch her with your paws!’ It should be said that he was terribly jealous. At that time, one decided to put a memorial plaque on the house in Aseyev’s honor. Zverev began to speak out against the plaque, saying that it was totally pointless. “Aseyeva had three sisters: Maria, Nadezhda and Vera. They tried to forbid Anatoly from coming to Oksana’s place. They said that she should break up with him and that he would be her demise. Anatoly waged a war against them, calling them ‘attic hags’. In short, there were a lot of funny and unusual situations. “I was once struck by his phone conversation with Aseyeva. He kept chastising her with very rude words, and I simply couldn’t bear it. ‘Listen,’ I told him, ‘either stop it immediately or hit the door. I can’t listen to that.’ Yet he continued to chastise her, while she, to my great surprise, listened to him and returned in kind. And then I thought, ‘There’s something wrong with me, not with them.’ I understood that I was simply not ready for such relations that were not just good but big and powerful. That’s how I would characterize their relations: powerful. They were very complicated, yet they were equal relations. She was madly in love with him. I think that he was someone who could replace something for her, remind her of something, and give her something in her desolate old age. After all, she was already getting very little at the time. Her life mostly boiled down to eternal rummaging in archival material. Numerous dissertations had already been written about Aseyev’s work, and Oksana could only recount different facts and situations relating to him. In contrast, Zverev was totally unpredictable. She adored his artworks, and he gave them to her in large quantities. She recalled how he lay in Tarusa with a broken arm and a broken leg and incessantly painted her portraits. As to me, I greatly regretted that he had not painted her portraits in 1955 or 1957 or 1959, say, when he was at the height of his creative powers. He naturally tried to please her and made her look younger on the portraits. That was how he perceived her, in any case. “Of course, this meeting and love affair between Oksana and Tolya had a special meaning. After all, he felt safe when he was with her: she was like a brick wall behind which he could hide and take refuge. I once had a very serious talk about this with him. In fact, he was terribly afraid of reality and was constantly on his guard. He was afraid that they would shut him up in a psychiatric hospital and dreaded of being put in a drunk tank. He finally learned to be careful and tried to go everywhere by taxi and spend less time in public places where he could be arrested. Was he ever confined to a psychiatric hospital? Although I never asked him about it, it seems that he was at one point. By the way, Oksana and Costakis visited him there. Yet they were well-wishers that realized that he needed medical assistance. They thought that he would get medical treatment and become a totally outstanding artist. However, it was very difficult for him not to drink, except in exceptional circumstances. Nevertheless, he once told me, holding his hand next to his heart, ‘Old man, I should stop drinking.’ ‘What’s the matter?’ I asked. He replied, ‘My heart aches. Yet, you know, I thought about quitting drinking and becoming very healthy. Yet only football players are healthy, old man.’ He said it quite earnestly and without joking: only football players could be healthy. It was 1984. “After Zverev’s death, I decided to take a picture of his room. That very room in his Sviblovo apartment in which he spent the last hours of his life. I asked friends that came there not to touch anything so make the photos as authentic as possible. When I came there, I was astonished. I saw that everything in the apartment had been displaced and turned upside down: even the bed had been moved from its place. It was as if the apartment had been searched. And all of this was done by people that had been close to him. I won’t cite their names here. That’s not my intent. All the people that did it know whom I’m speaking about. What were they looking for? I don’t even want to think about it. They were apparently looking for paintings – for everything that could bring them a good profit later on… “Zverev died on December 9, 1986. He suddenly felt bad in his apartment in Sviblovo, which he disliked so much and that he prophetically called “Giblovo” (from the Russian word gibel’ ‘death’). The doctors at the hospital where Zverev was taken said that his condition was hopeless. He had had a stroke. I recall seeing him a day before he died. He lay unconscious and breathed unevenly. Yet he was so calm and blissful, as if he was surrendering himself. It was the first time that you could put your hand on him… And that was all. The next day, he died. The doctor said, ‘He was incredibly strong, you know. His brain was simply floating in blood.’ “Zverev’s death made us look at him in a different light. It was clear that a great artist had died. Saying farewell to him, we were saying farewell to freedom in a way. A film about his funeral was made by the photographer Sergei Borisov. The film is totally authentic. It shows how touchingly people were saying farewell to him and how much they loved him. Not everybody, of course. Some people may have recognized his talent yet did not assess it so highly that they felt it necessary to come to the funeral of such a person and such an artist.” |

|

|

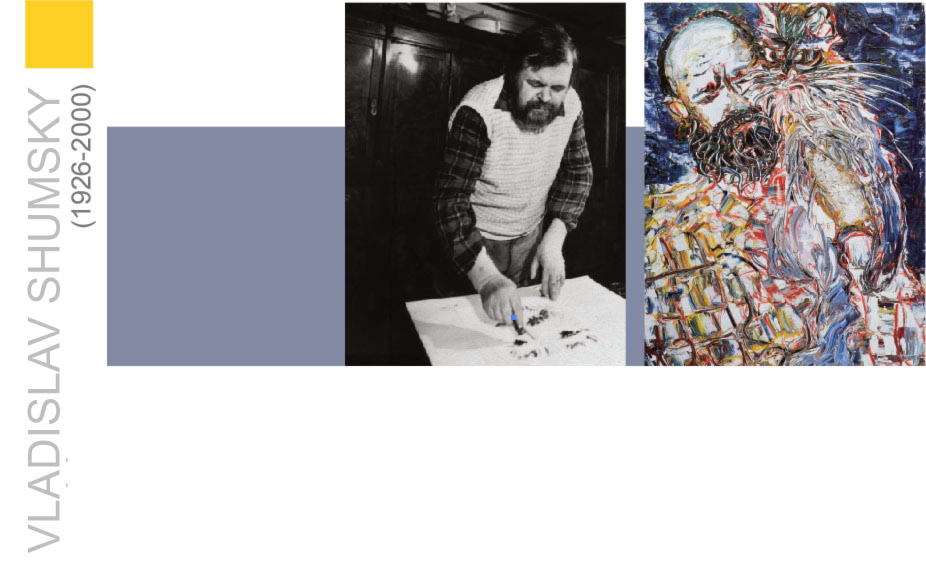

VLADISLAV SHUMSKY (1926—2000)

A historian, political scientist and writer, Shumsky graduated in 1949 from the Moscow State Institute of International

Relations where he majored in the History of International Relations. He worked as a TASS editor in Moscow, a researcher-translator in Vienna, and a journalist in Bonn and West Berlin. From 1956 to 1976, he was editor-in-chief at the Publishing House of International Relations of the State Committee of the USSR Council of Ministers and senior scholarly editor at Progress Publishing House. Shumsky defended a Candidate of Science degree in History. He was a member of the Russian Union of Journalists and Union of Writers. He collected Zverev’s works and wrote numerous articles and memoirs about the artist. for more details |

|

A historian, political scientist and writer, Shumsky graduated in 1949 from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations where he majored in the History of International Relations. He worked as a TASS editor in Moscow, a researcher-translator in Vienna, and a journalist in Bonn and West Berlin. From 1956 to 1976, he was editor-in-chief at the Publishing House of International Relations of the State Committee of the USSR Council of Ministers and senior scholarly editor at Progress Publishing House. Shumsky defended a Candidate of Science degree in History. He was a member of the Russian Union of Journalists and Union of Writers. He collected Zverev’s works and wrote numerous articles and memoirs about the artist.