|

COLLECTION

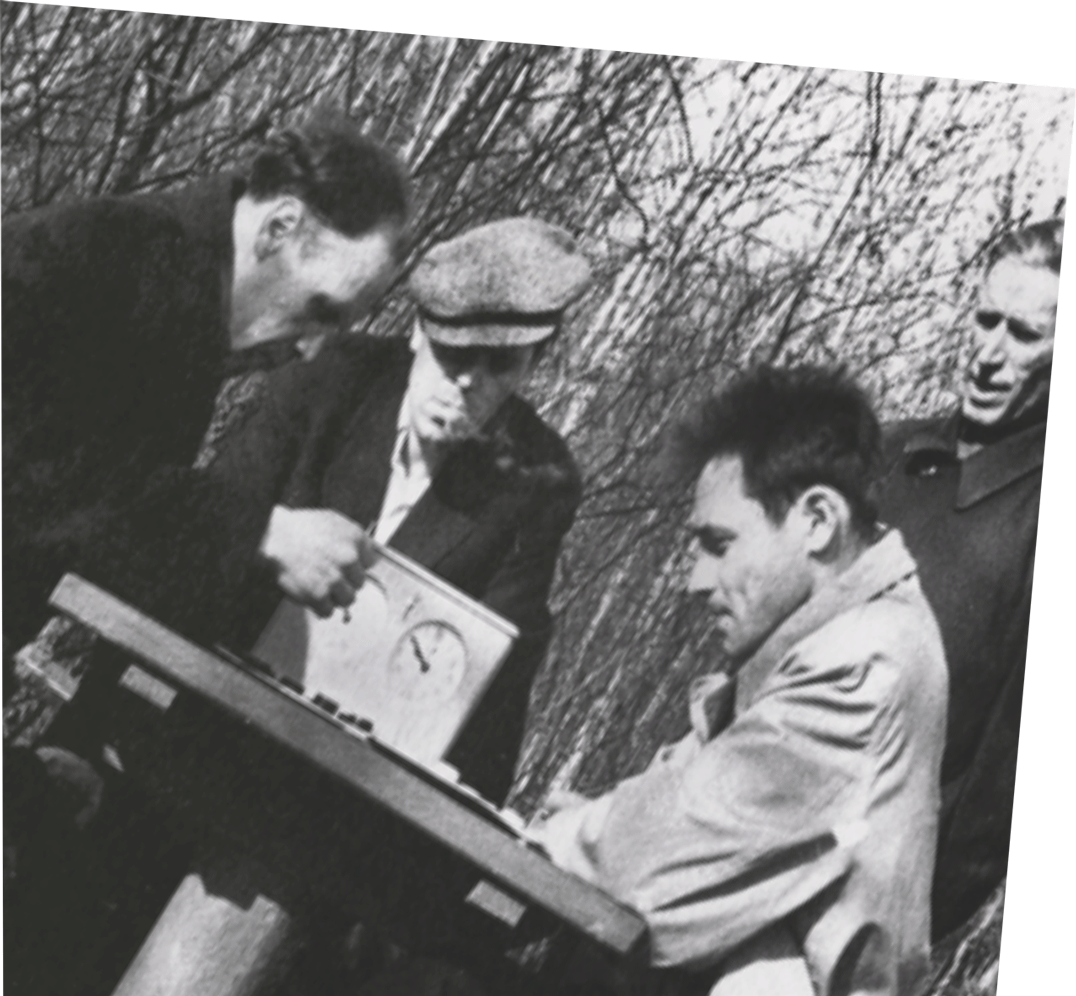

The museum's collection includes over 1,500 works by Anatoly Zverev and the artists of his circle. It is constantly incorporating new masterpieces. The museum's archive contains documents linked to Zverev's life and work: letters, prose, poetry, and treatises on art. In 1978, Costakis gave the Tretyakov Gallery a substantial part of his collection of Russian avant-garde. In 2014, the collector's daughter Aliki Costakis donated to the AZ Museum over 600 of the artist's works from the collection of her father.

|

|

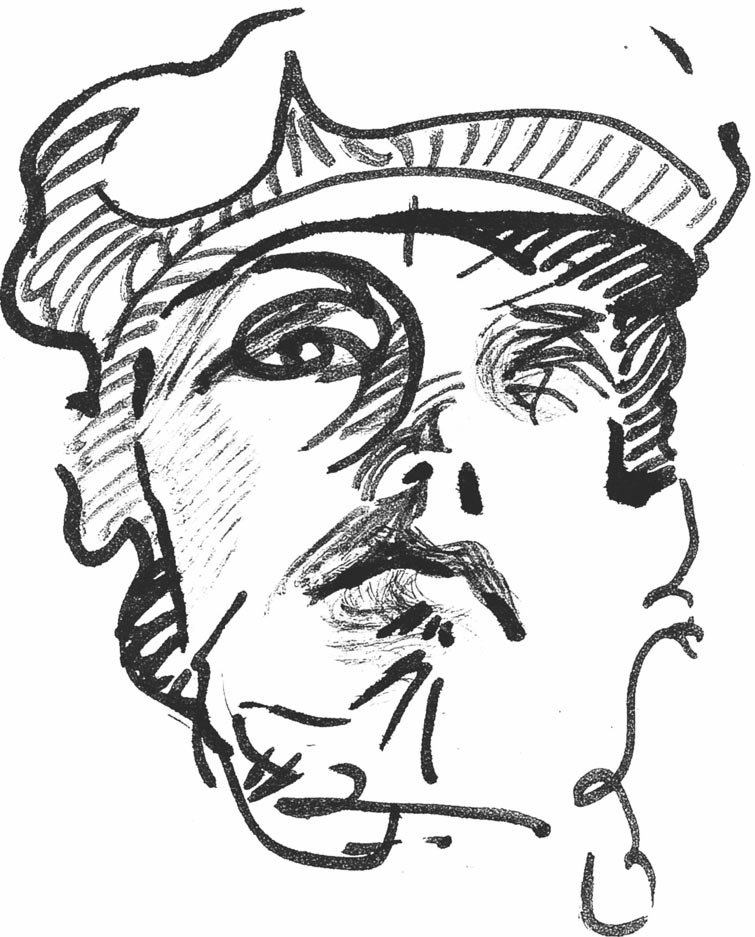

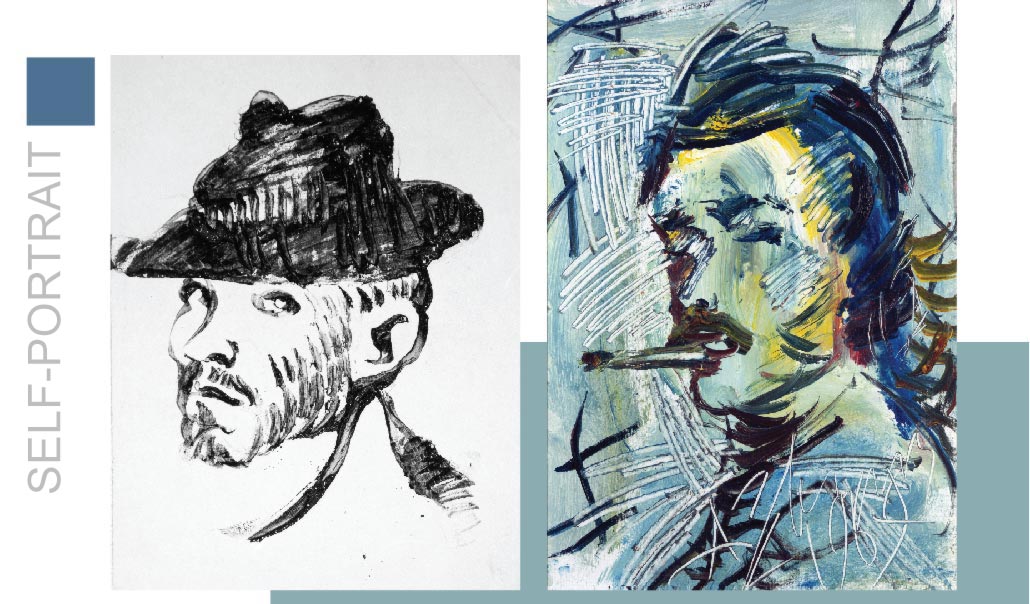

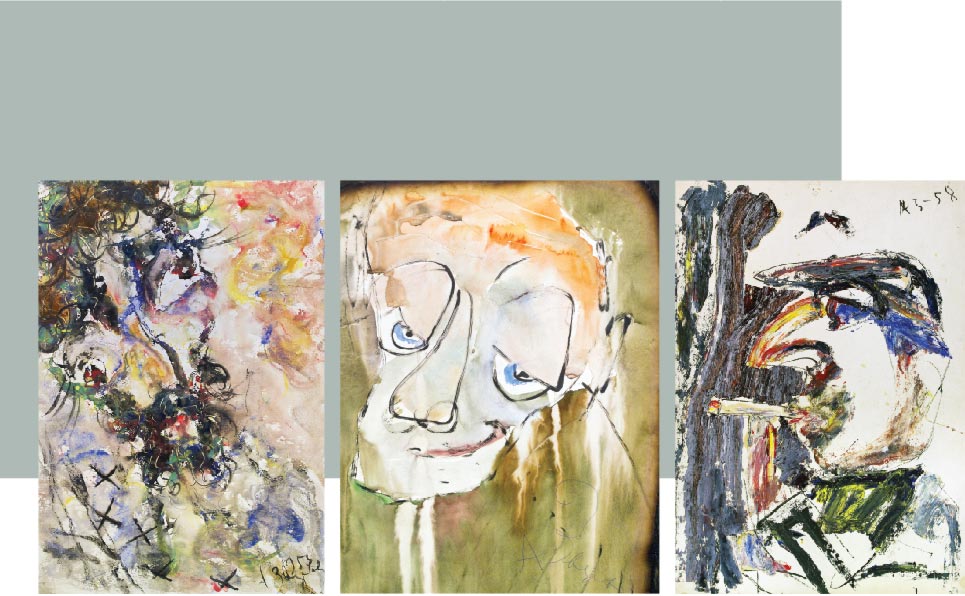

Self-portrait, 1950-s

Self-portrait with a cigarette, 1969

|

|

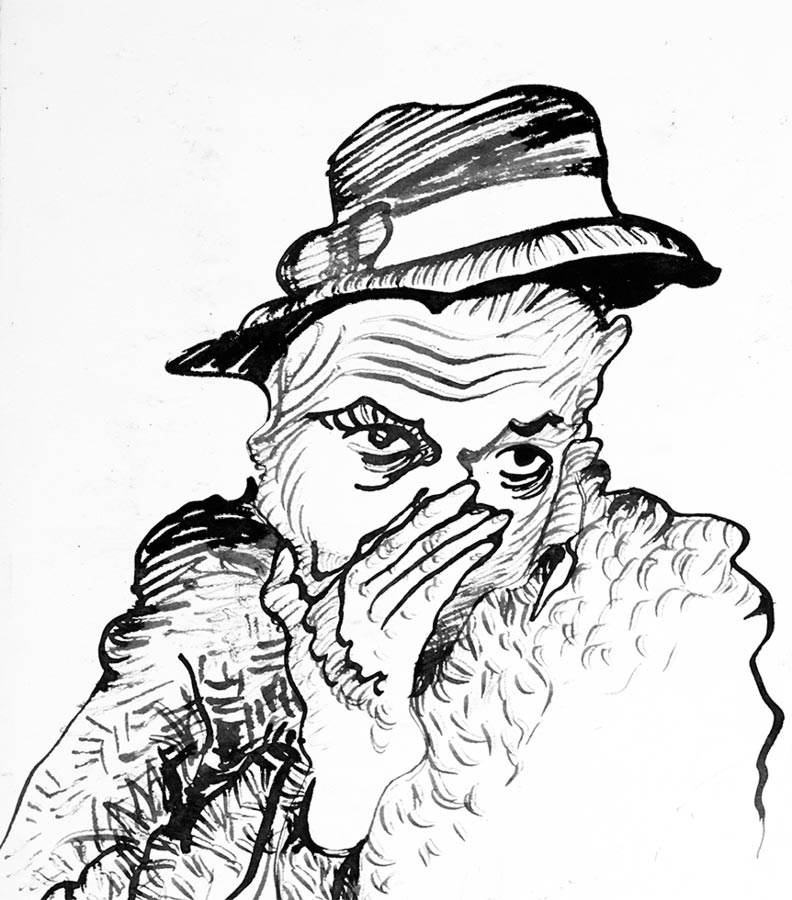

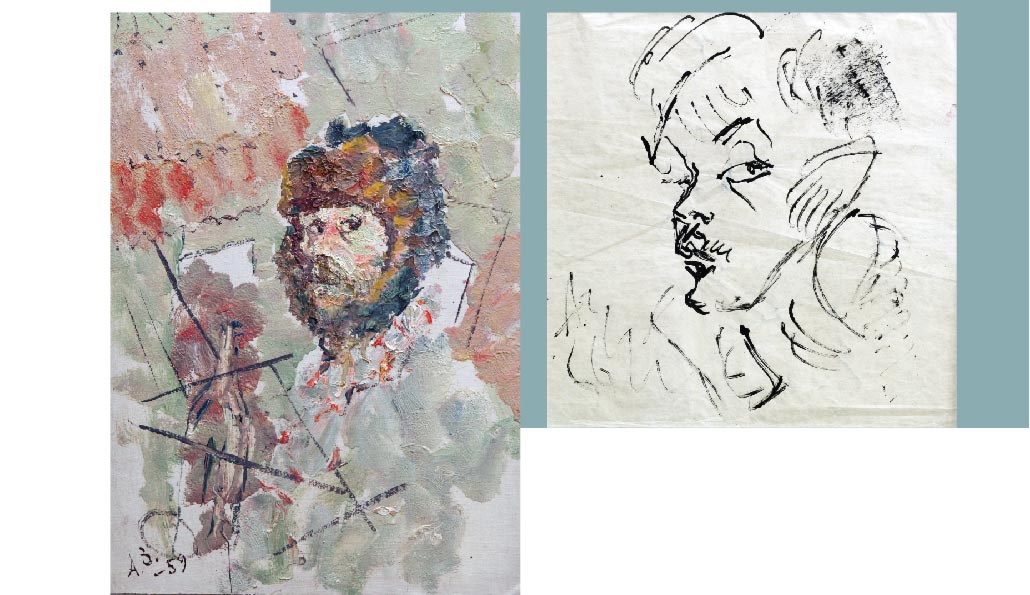

Self-portrait, 1959

Self-portrait in a hat, 1957

|

|

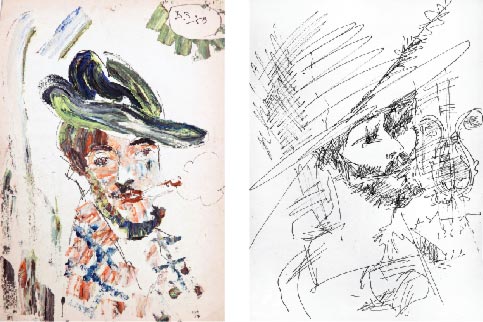

Self-portrait, 1958

Self-portrait, 1968

|

|

Self-portrait, 1957

Self-portrait

|

|

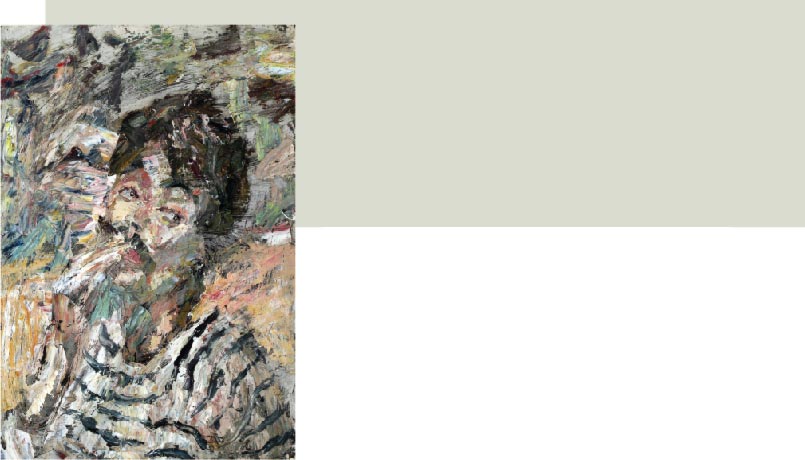

Self-portrait in a striped vest, 1950-s

Self-portrait, 1957

|

|

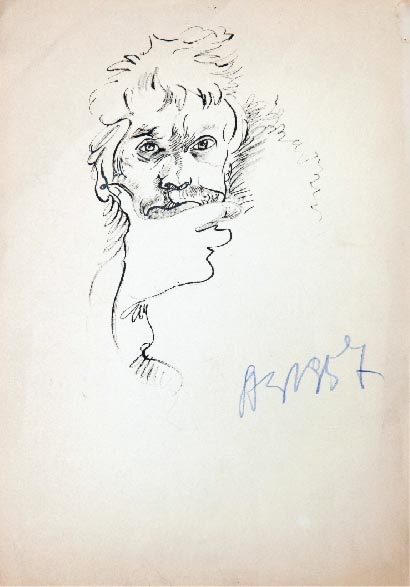

Self-portrait, 1957

|

|

Self-Portrait

Zverev's enormous number of self-portraits represents a long and very personal conversation between the artistand those that interested him. Here we see Zverev in a felt hat with the profile of Van Gogh with high cheekbones. Here he resembles Van Gogh once again: a surprised red-haired dreamer in a fur cap with ear flaps tied below his chin. Here we see a dark and profound Vrubel-like self-portrait, a paraphrase of The Demon. In each portrait, we see Zverev engaged in a conversation with other great artists on an equal footing. |

|

Pelican, 1956

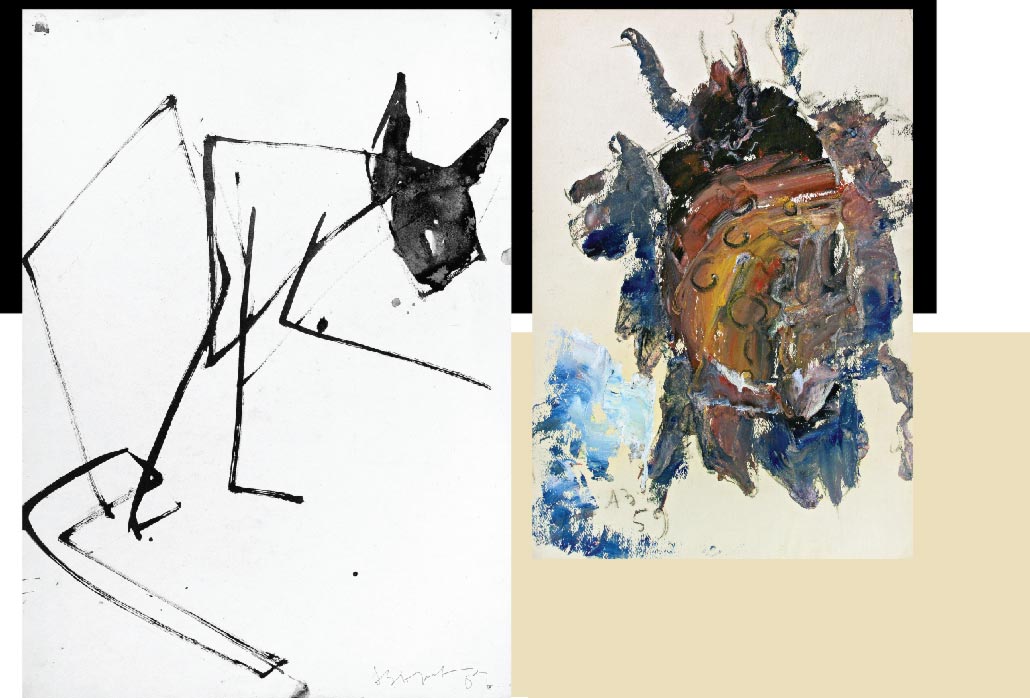

Horse, 1950-s

Fallow-deer, 1959-60

Hoopoe, 1957-60

|

|

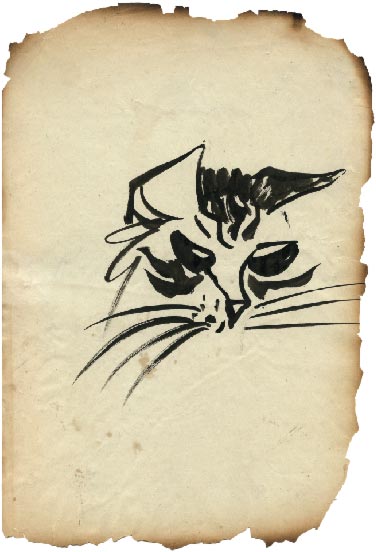

Cat, 1956

Ladybird, 1959

|

|

Cat, 1950-s

Zebra, 1956

|

|

|

Animal Drawings

Zverev's animals are astonishing. His animalistic works embody the absolute freedom of which theartist always dreamt and in which he lived. Zverev went to the zoo and drew animals in confinement. Yet his drawings do not show cages: the animals look natural and unconfined in their plastic and dynamic motion. They may be called Zverev's manifesto about the essence of freedom, including human freedom. |

|

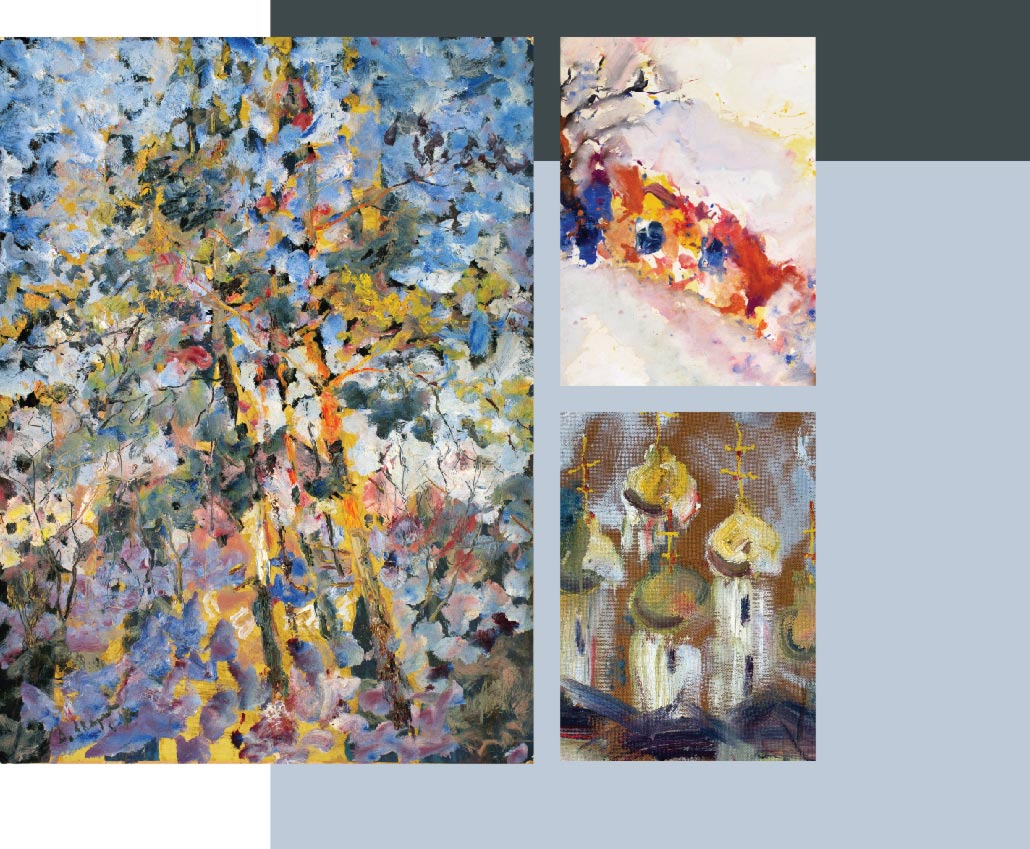

Sunrise, 1957

Landscape, 1958

Golden domes, 1959

Landscape with a tree, 1958

|

|

Pines, 1958

Winter landscape, 1958

Church, 1950-s

|

|

Landscapes

Zverev's landscapes are tender and limpid like spring flowers. They show glimmering golden church domes that seem to float in the air, the openwork of trees, birches with opening leaves, and pine trees with dark trunks in the summer heat. Light is the main protagonist of his landscapes: it is the medium in which everything (forests, fields and onion domes) floats and swims. Even in the twilight of Zverev's townscapes, warm sunlight emanates from the windows of houses.

|

|

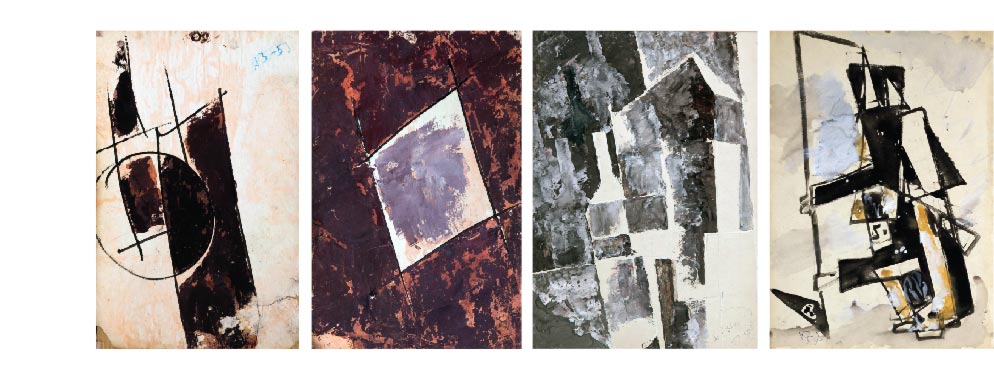

Suprematist composition, 1959

Suprematist composition, 1959

|

|

Suprematist composition, 1957

Suprematist composition, 1950-s

|

|

Suprematist composition, 1957

Suprematist composition, 1959

Suprematist composition, 1959

Suprematist composition, 1957

|

|

Suprematist composition, 1950-s

Suprematist composition, 1959

|

|

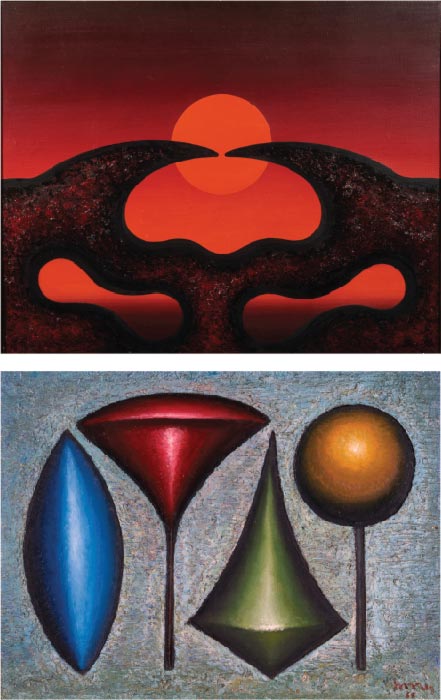

Suprematism

Zverev reinvented suprematism. He made it painterly and filled the clear geometric forms with dusky passion. Malevich painted balanced bright and dynamic compositions in a very fine and precise manner. Zverev suffused strict geometry with a dark and enticing play of colors, as if he had dropped the clarity of form into the water ripples in a deep dark well. |

|

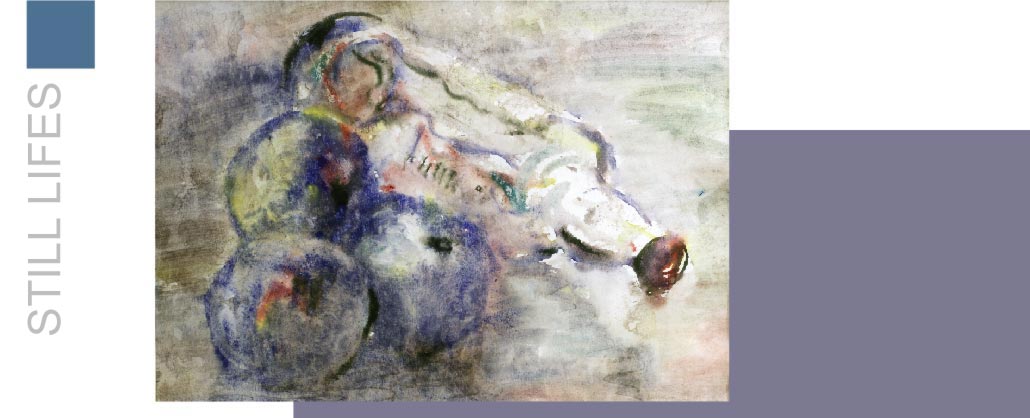

The bottle and apples, 1960-s

|

|

Bottles and apples, 1959

Flowers, 1960-s

|

|

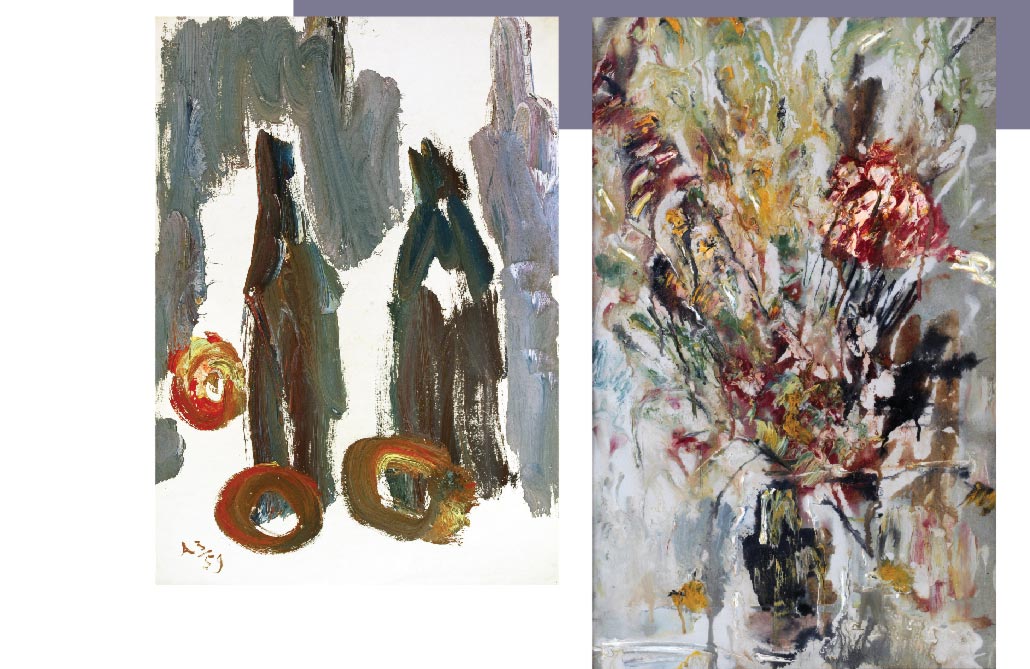

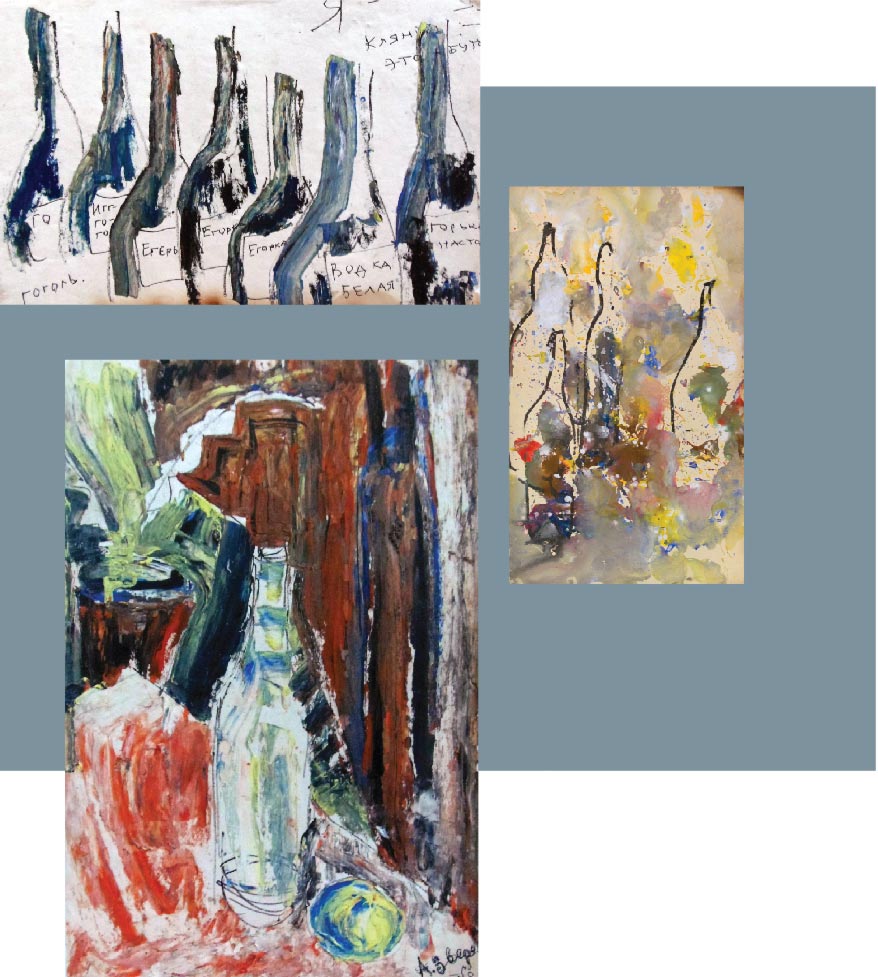

Seven bottles, 1957-1959

Bottles, 1958

Still life with a bottle, 1958

|

|

Still Lifes

Having assimilated the spirit of early 20th-century avant-garde and the philosophy of cubism, Zverev purified the still life from the over-expressiveness of acute angles and the disintegration of geometric forms. His bottles, outlines of fruit, and musical instruments are not split into their constituent parts. Instead, they attract attention by the virtuoso correlation of pure and complete forms that repeat each other. In Zverev's still lifes, all matter becomes aerial and ready to take off and dissolve in space at any moment.

|

|

Illustration to The Golden Ass, 1950-s

|

|

Illustration to The Golden Ass, 1950-s

Illustration to The Golden Ass, 1986

|

|

Don Quixote and Sancho Penza, 1975

|

|

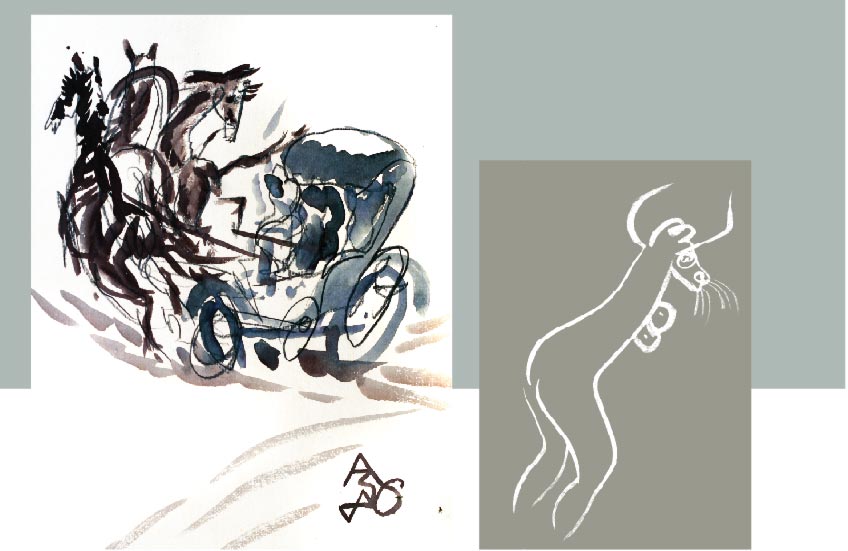

Illustration to Gogol's Dead Souls, 1986

Illustration to The Golden Ass, 1950-s

|

|

Illustrations

Zverev's illustrations to Gogol, Andersen and Apuleius are more than just depictions of literary images and themes. Zverev's vision of every great writer is an attempt to include him in his own artistic world, to assimilate him and to look at him through the lens of his own worldview: the dark and gloomy fantastic world of Gogol's Viy, the lightness and tenderness of Andersen's fairy tales, and Apuleius' elegant hedonism. Zverev does not simply illustrate literary works but also makes very complex double portraits. The grandiose figures of great writers and of the great artist emerge in this kaleidoscope of drawings. |

|

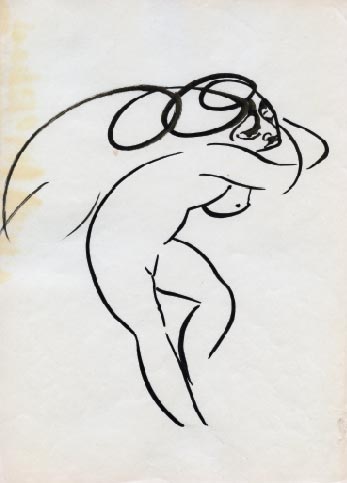

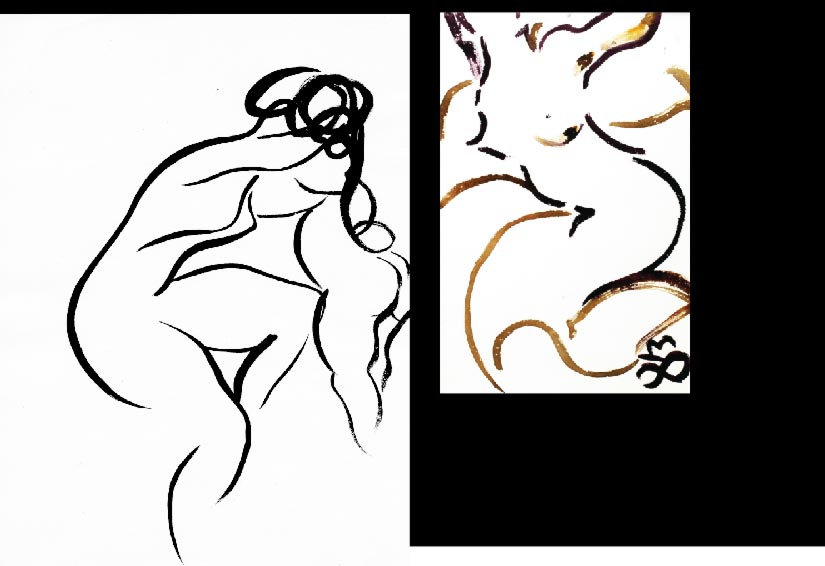

Nude, 1950-s

Nude, 1950-s

|

|

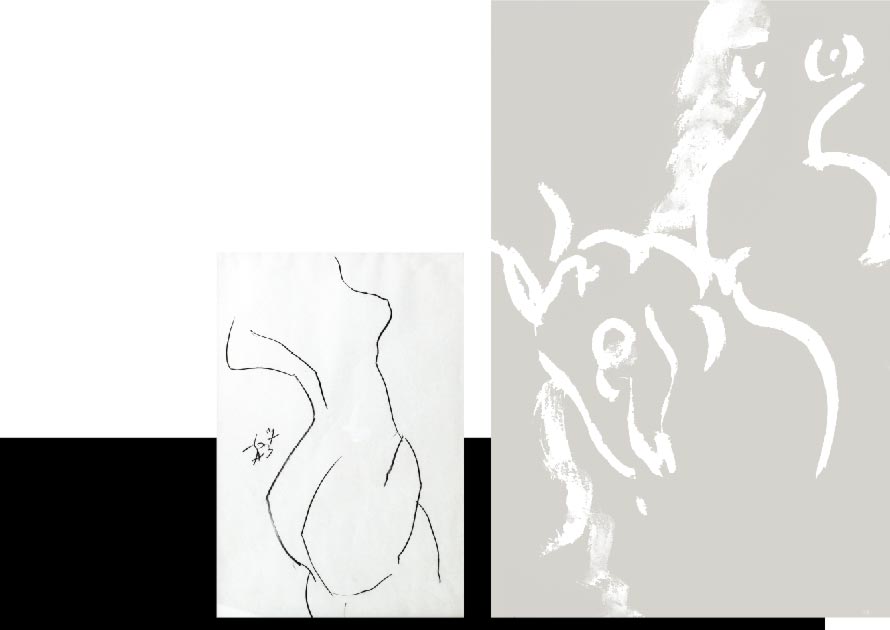

Nude, 1950-s

|

|

Body, 1967

Amazon on a horseback, 1983

|

|

Nude, 1950-s

Female body, 1983

|

|

Nudes

Zverev's series of nudes are a real miracle. It is no surprise that Picasso called him the best Russian draftsman. Every line and every perspective of his offers an explosion of tenderness, sensuality and joy. Every work contains the sound of the inspired music of life itself. The virtuoso brushstrokes resemble a conductor's baton that traces aerial figures of pure delight. |

|

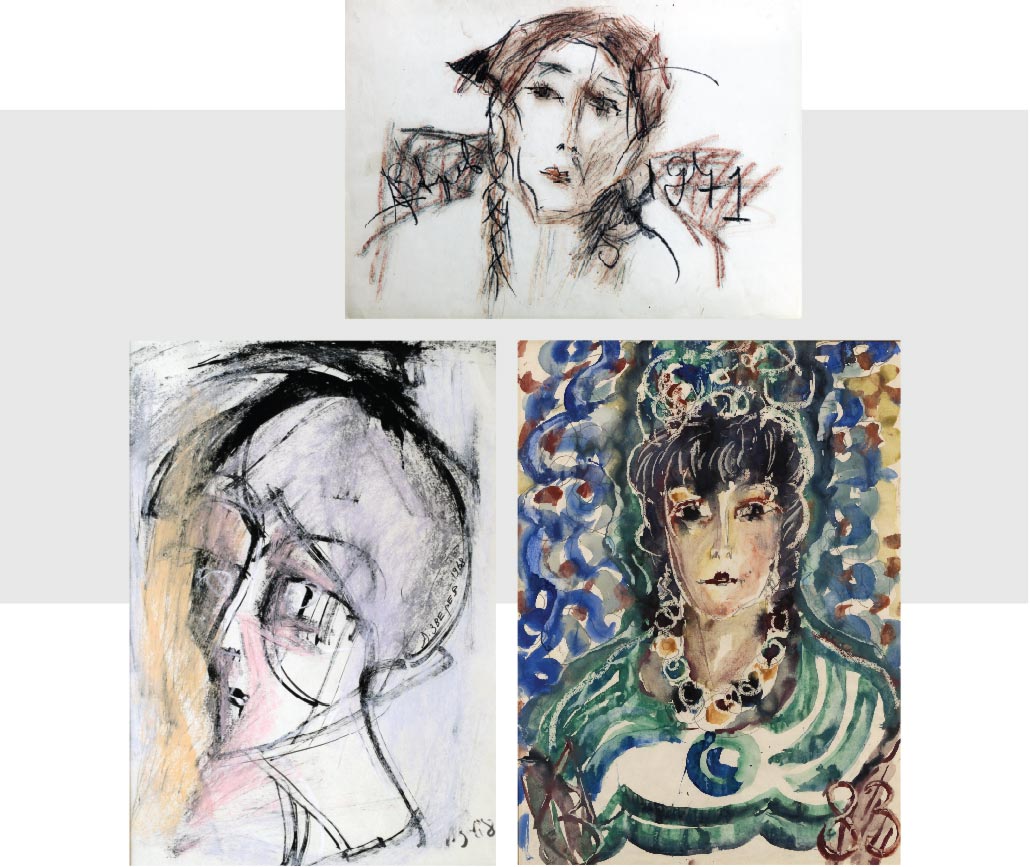

Portrait of O. Aseeva, 1969

Female portrait, 1967

|

|

Female portrait, 1976

|

|

Lilya, 1958

Portrait of O. Aseeva, 1971

|

|

Female portrait, 1968

Female portrait, 1983

|

|

Female Portraits

Zverev's gaze is penetrating and precise. In the endless succession of female heads, he attentivelyseizes the unique features of each model – the perspective, the half-sunk eyes, the misty gaze, and the tenderness of the play of pastel tones. Each portrait is a deep and lyrical spiritual revelation. Taken together, they create a single eternal image of the "fair lady". |

|

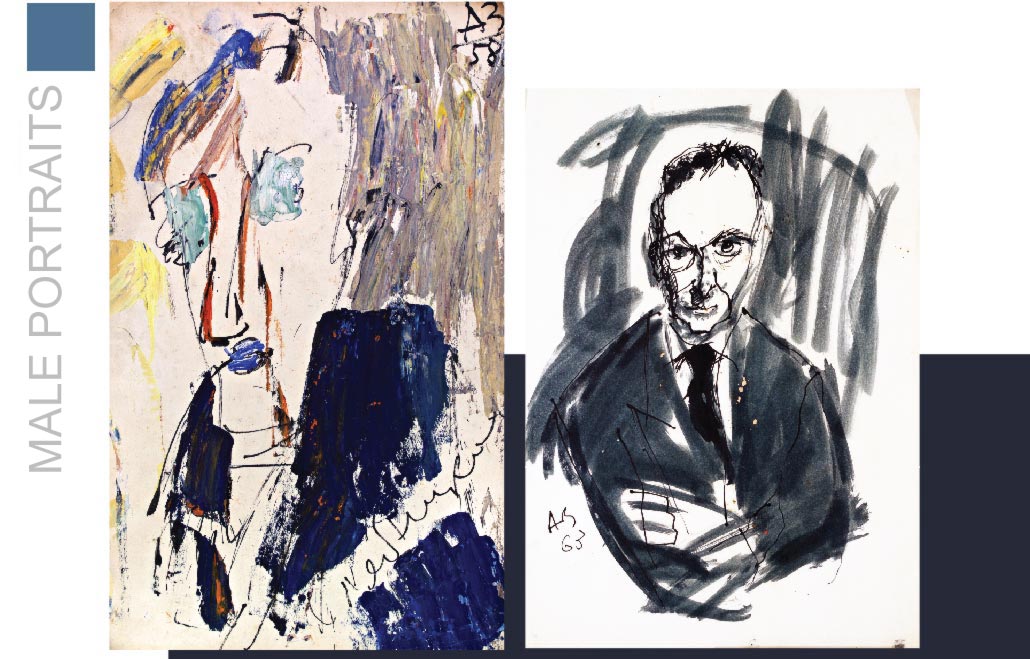

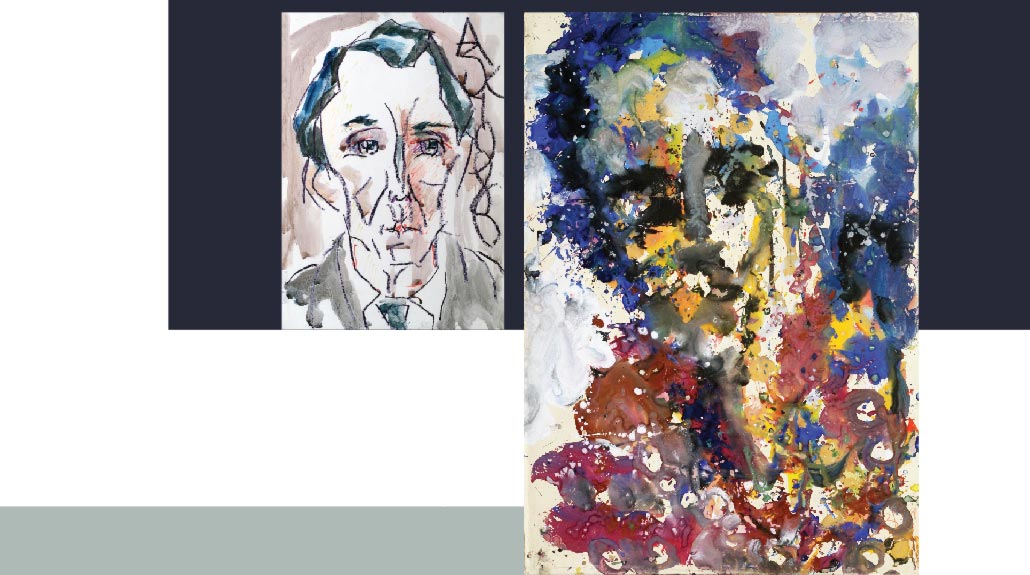

Portrait of V. Khlebnikov, poet, 1950-s

Portrait of I. Markevitch, conductor, 1963

|

|

Male portrait

Male portrait, 1958

|

|

Male portrait, 1958

Portrait of R. Falk, artist, 1957

A man in a cap, 1958

|

|

Male Portraits

Zverev's male portraits are open and expressive. The eyes and faces seem to swing open towards the viewer and show the energy of passion and movement. Zverev paints male faces using gouache, watercolor and pencil, choosing the best technique for each person. Zverev's friends and acquaintances break out of the paper, as if bursting through it, and surround him in their polyphony.

|

|

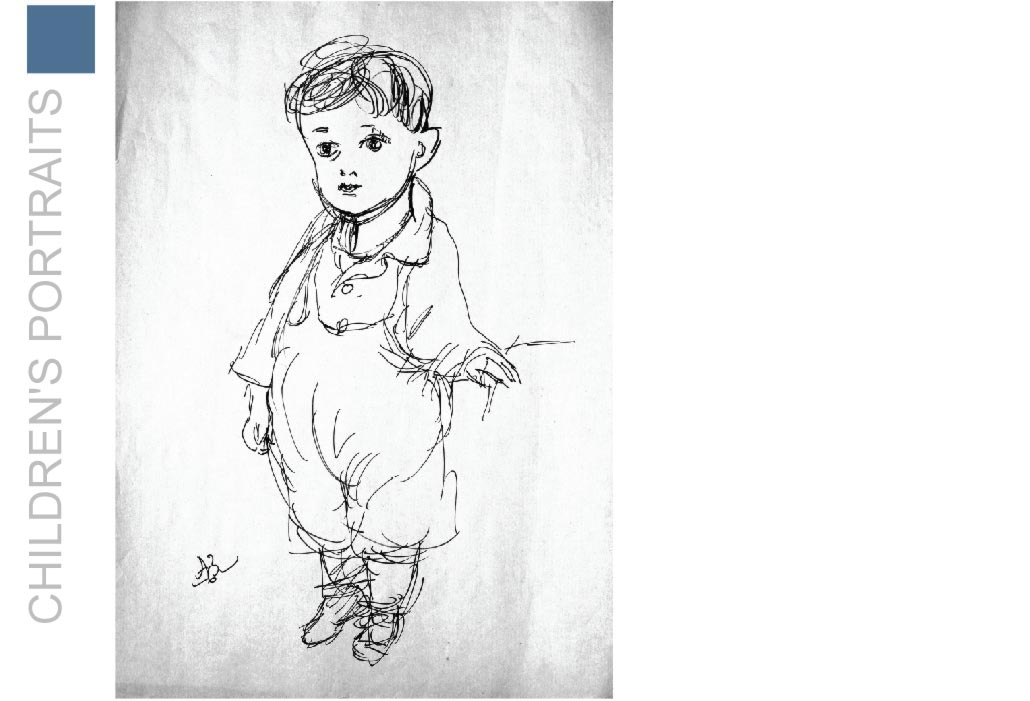

Misha, 1963

|

|

Son Misha and daughter Vera, 1962

|

|

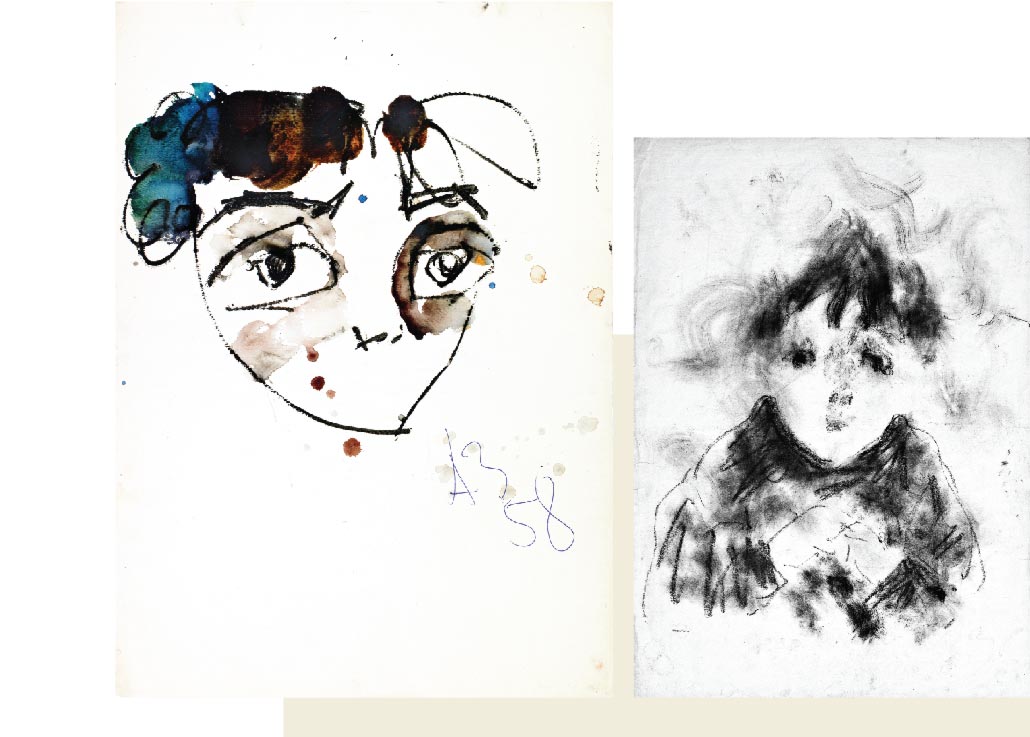

Girl's portrait, 1958

Portrait of Sasha Costakis, 1959

|

|

A boy, 1954

Son Misha and wife Lusya, 1962

Son Misha, 1962

|

|

Children's Portraits

Zverev's portraits of children always contain a remarkably perceptive gaze into the future. Zverev approached children, the sons and daughters of his friends, with a rare tenderness and attentiveness. In his children's portraits, Zverev did not depict a sweet natural charm and spontaneity. He showed children as serious and concentrated people, managing to pierce the present to get a glimpse of the future. |

|

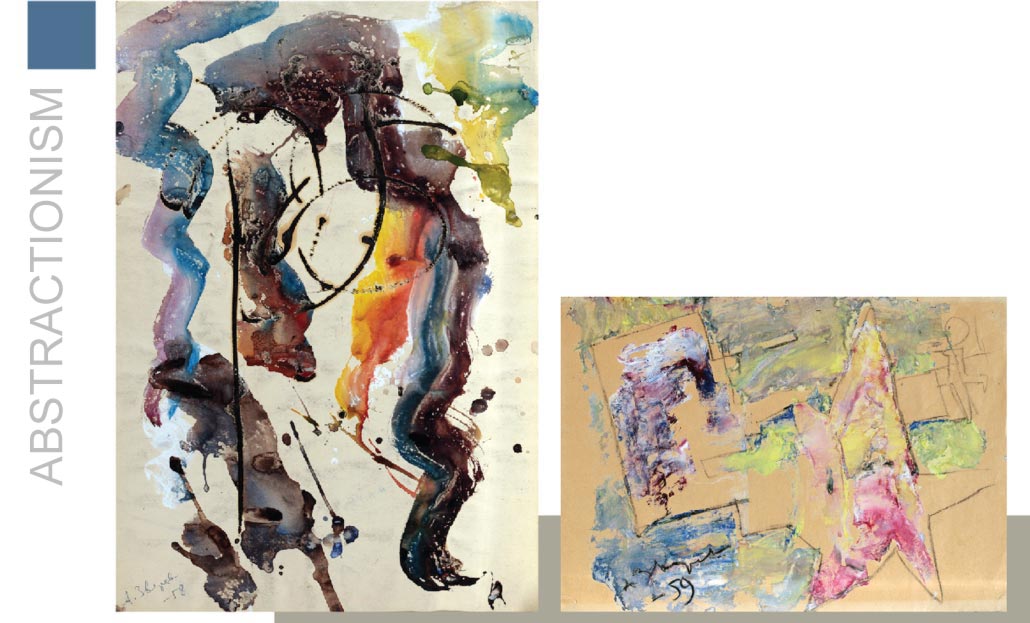

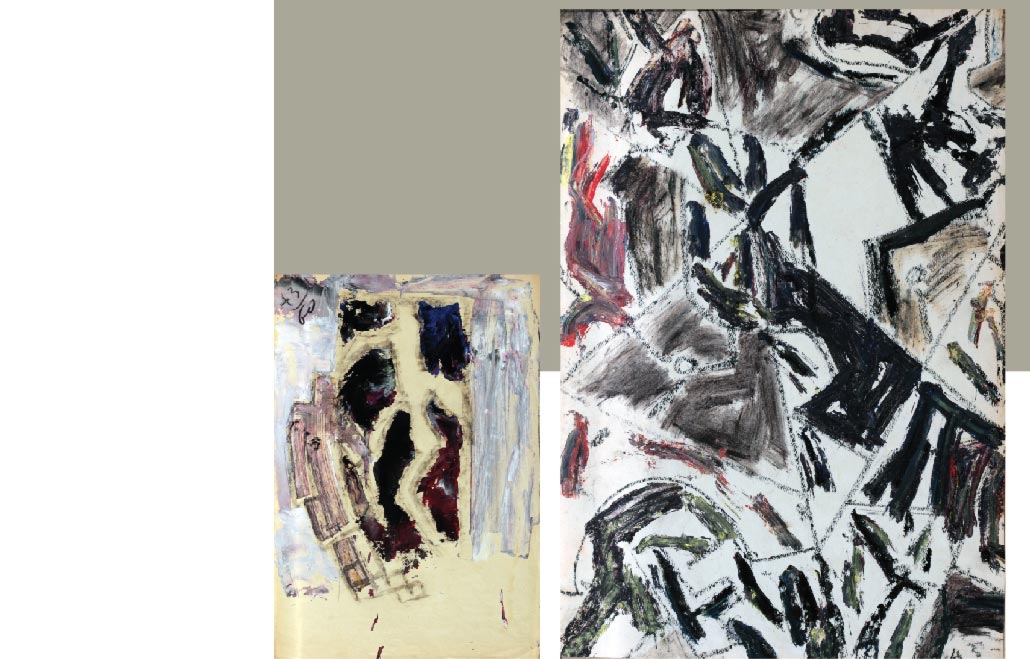

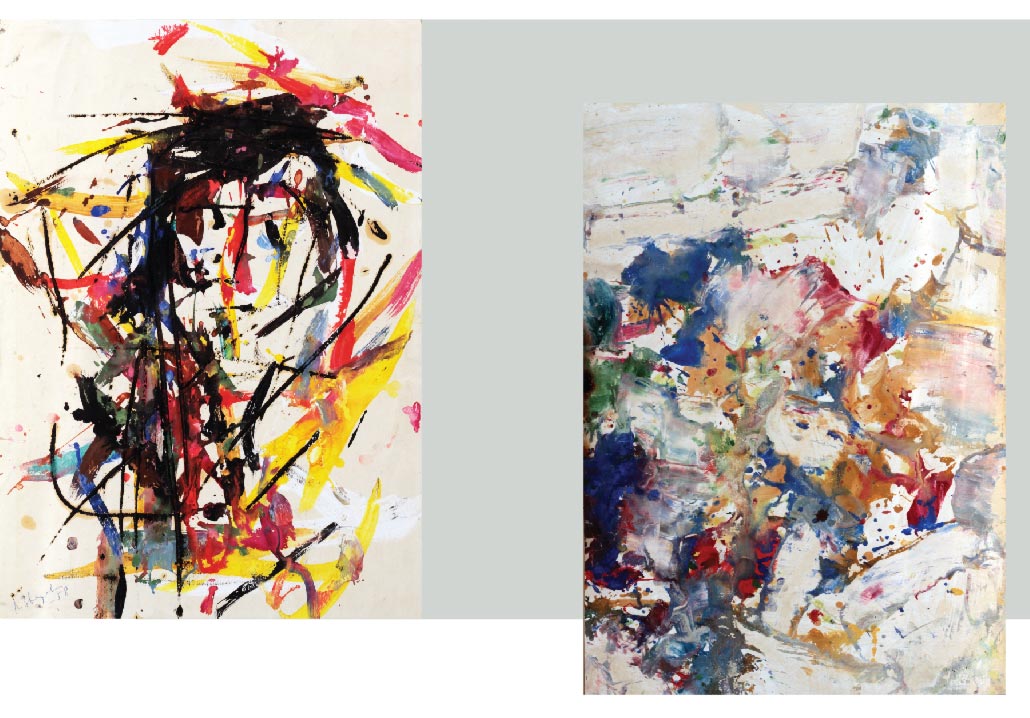

Abstract composition, 1958

Abstract composition, 1959

|

|

Abstract composition, 1960

Abstract composition, 1950-s

|

|

Abstract portrait, 1958

Abstract composition, 1950-s

|

|

Abstract composition, 1959

Abstract composition, 1957

|

|

Abstractionism

In his Treatise on Painting (1963), Zverev wrote, "Abstractionism literally burst into a peace-loving and conservative world, condemning itself to the attacks and the total disbelief and mockery of society… Nevertheless, abstractionism made a great impact and spread like a typhoon in places that were still frequented until recently by traditional painters, timidly copying city-dwellers and tsars that were preparing for death. Malevich's black square! Bluish-black with red and yellow tones! With dashes and stripes piercing! the sky! and the clouds! Kandinsky's arrows! killing while storming the great sign…" Each of Zverev's works became a true manifesto of abstractionism as pure art.

|

|

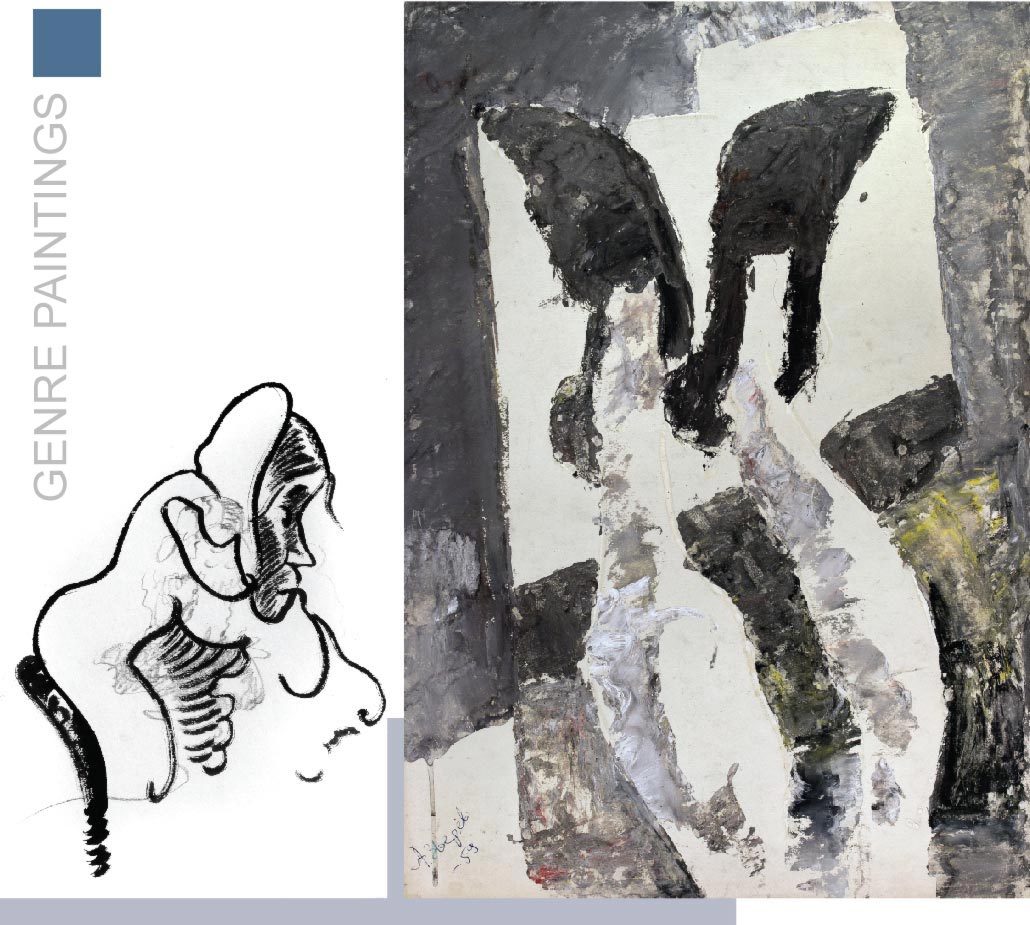

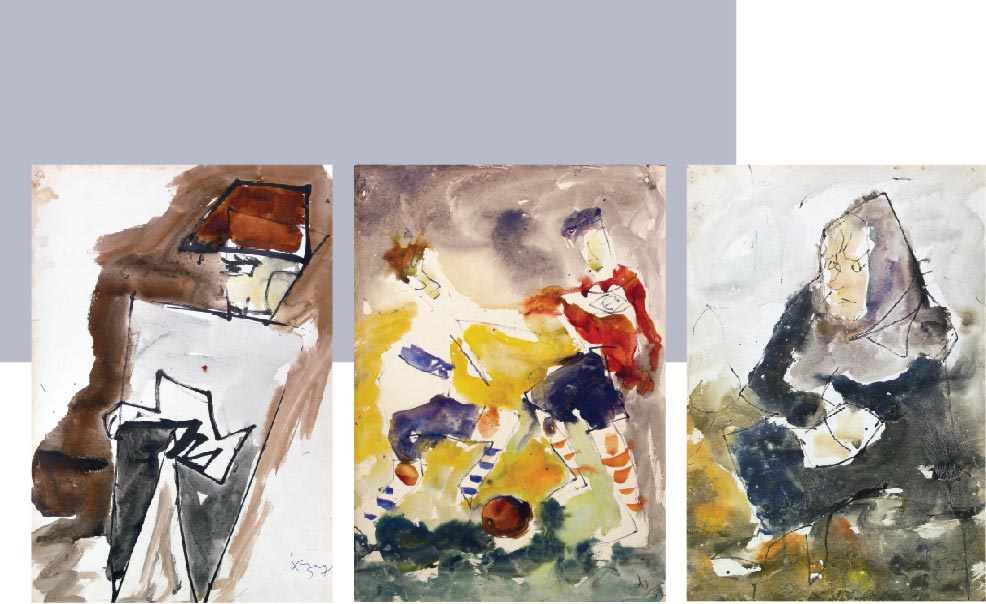

Untitled, 1957-59

A woman, 1950-s

|

|

Man in a fez, 1957

Football-players, 1957

Old lady with a shawl, 1957

|

|

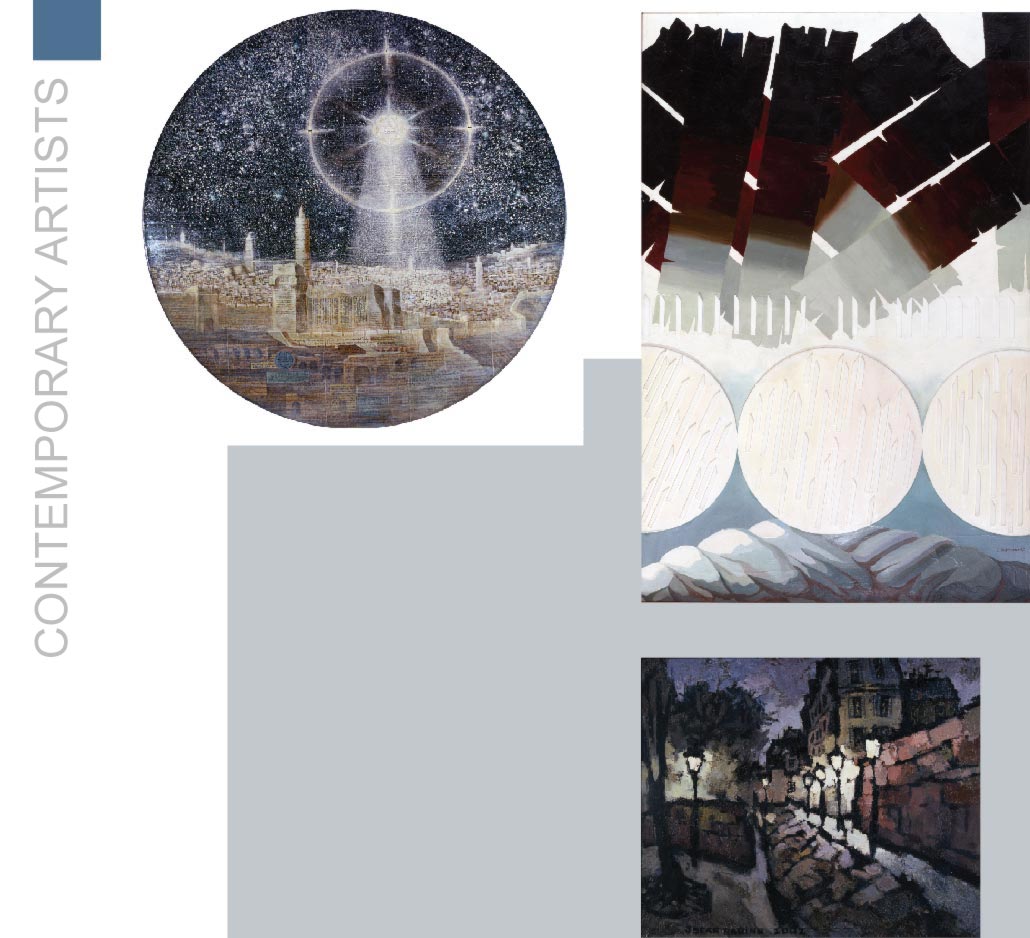

D. Plavinsky. Night sight in Jerusalem, 2005

L. Masterkova. Composition №18, 1978

O. Rabin. Night in Monmartre, 2002

|

|

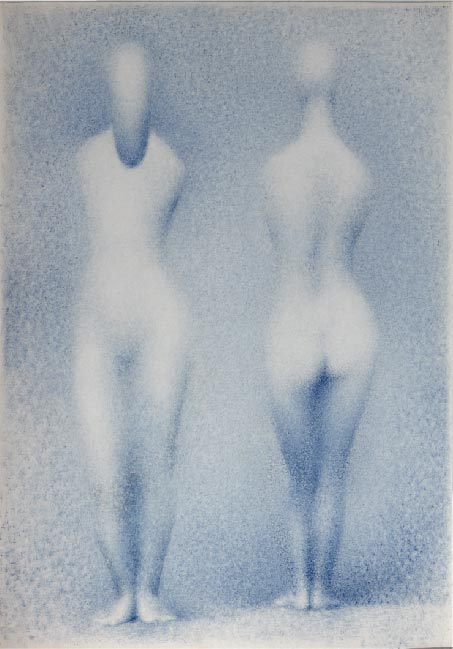

V. Sitnikov. Nudes

|

|

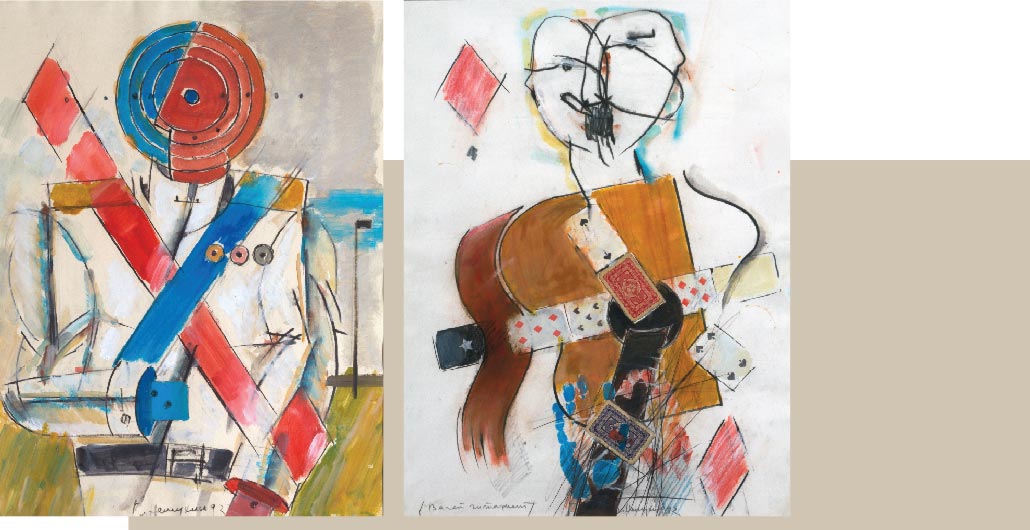

V. Nemukhin. Jack-target, 1992

V. Nemukhin. Jack-guitarist, 1992

|

|

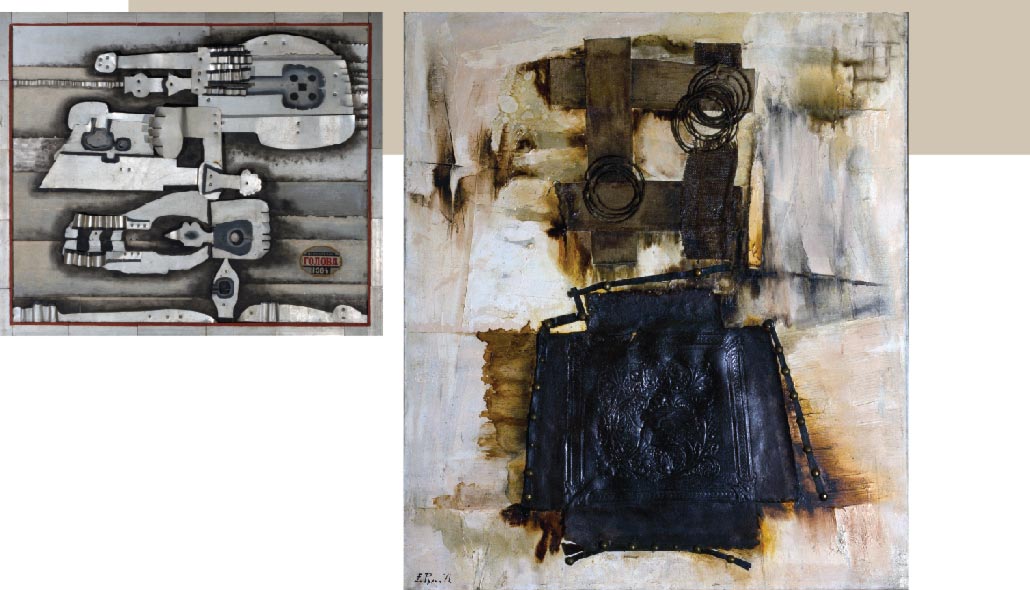

V. Yankilevsky. The Head, 1967

E. Rukhin. Untitled, 1971

|

|

L. Kropivnitsky, 1957

E. Neizvestny. Sculpture, 1960-s

|

|

N. Vechtomov. Landscape, 1990

V. Yakovlev. The flower on red background, 1990

Y. Sooster. Junipers

|

|

V. Yakovlev. The flower on red background, 1990

|