|

|

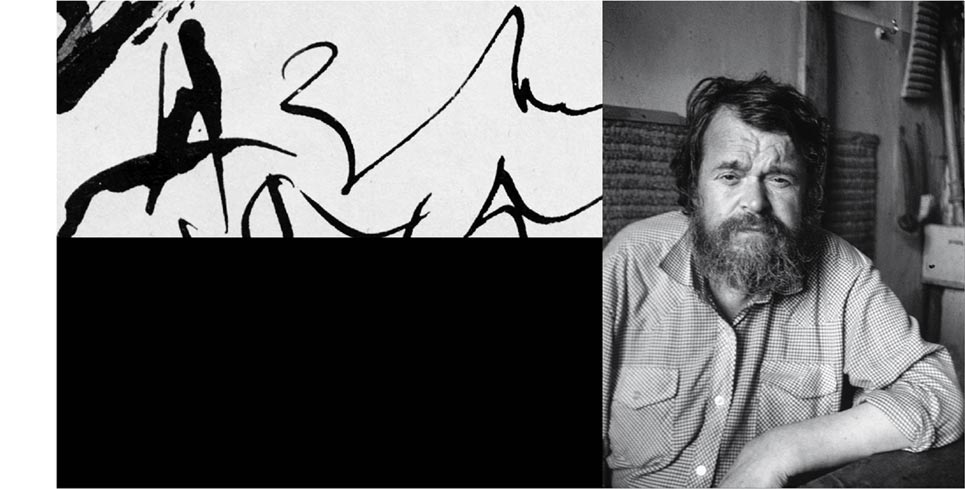

The AZ Museum is a museum of the Russian artist Anatoly Zverev, who was one of the most interesting figures of Moscow cultural life in the second half of the 20th century. Anatoly Zverev was formally close to the non-conformist movement, and he ranks among the best artists of this period. Nevertheless, the uniqueness of his artistic style and his multisided talent make it impossible to confine him within the boundaries of any narrow artistic period. The French conductor Igor Markevitch, who organized Zverev exhibits in Paris and Geneva in 1965, said that "Zverev is a 'phenomenon' – the phenomenon of a person that rediscovered the history of modern art".

Today, the heritage of Anatoly Zverev includes tens of thousands of works. His paintings are found in the world's leading museums from the Tretyakov Gallery to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in the best private collections. |

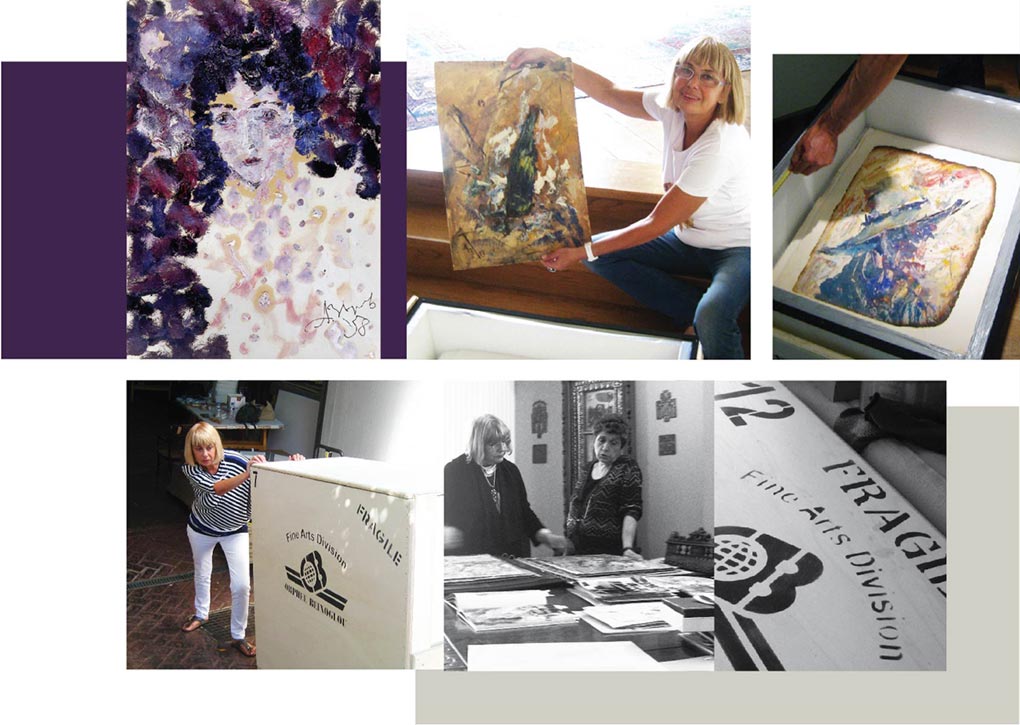

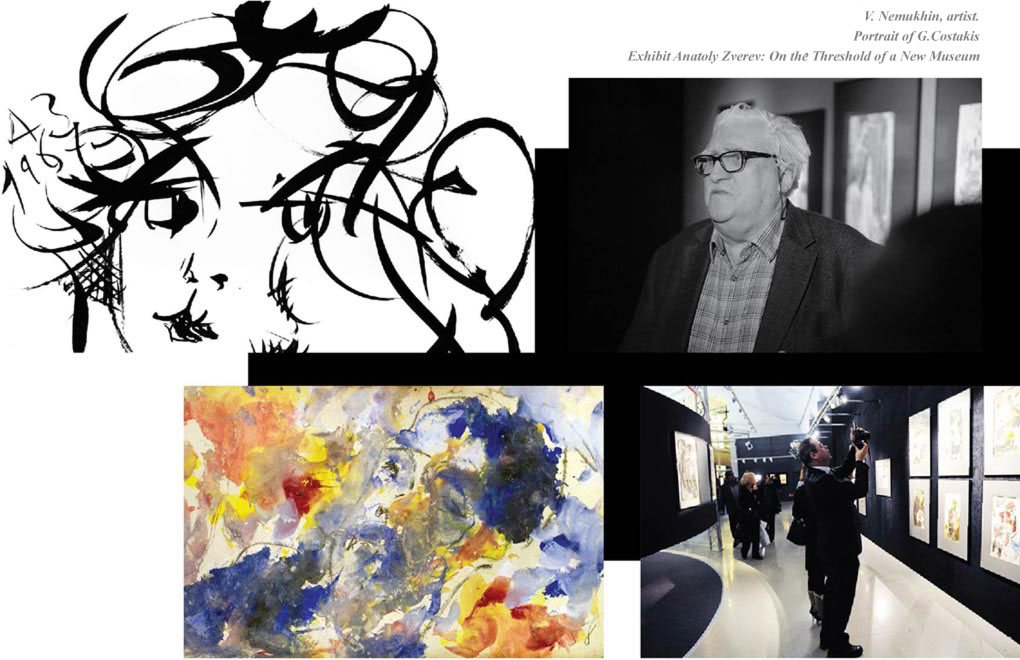

| The AZ Museum was established in 2013. Its founders were the collector and art patron Natalya Opaleva and the art curator Polina Lobachevskaya. The idea of creating the museum arose in 2012 when the exhibit Zverev in Flames was held at the New Manege. The exhibit presented Zverev's works from the collection of George Costakis; they had miraculously survived a fire at Costakis' dacha in the village of Bakovka next to Moscow in 1976. Over 30,000 people visited the exhibit during a month. The interest of the public at large in Zverev's work and personality became the starting point for the creation of the museum. As Polina Lobachevskaya said, "The idea of the museum was not artificial but arose as a response to people's spontaneous movement towards Zverev." The idea of creating the museum was supported by George Costakis' daughter Aliki, who donated over 700 works to the museum. This donation led to another exhibit that was held in 2014 and that presented the already existing (though not yet constructed) museum: Anatoly Zverev: On the Threshold of a New Museum. Over 40,000 people visited the exhibit during a month. The AZ Museum Publishing Project was presented at the exhibit.

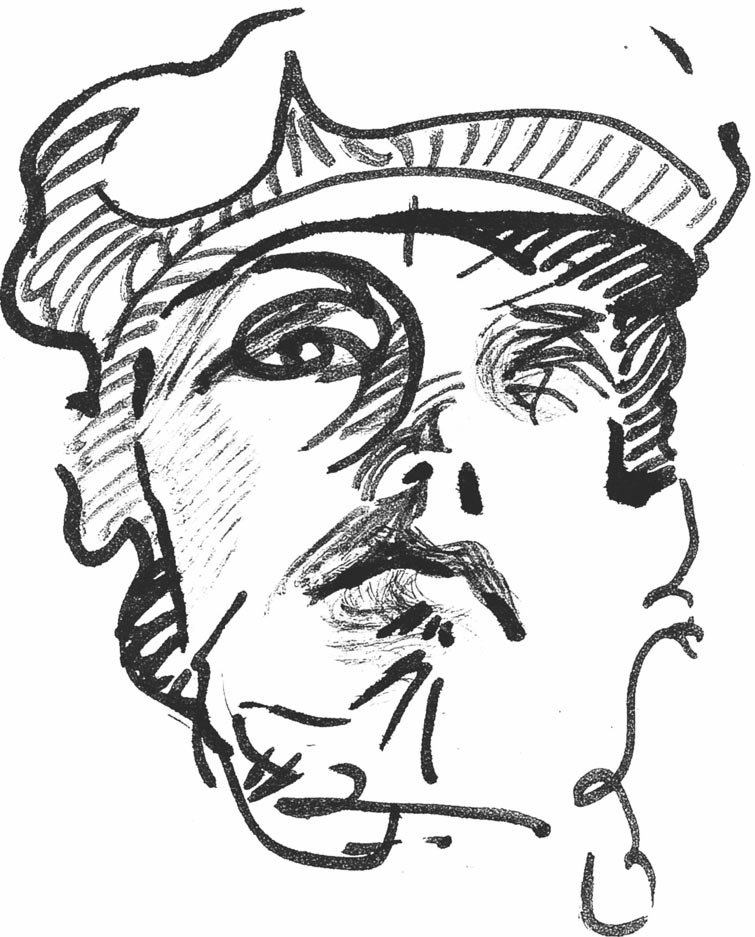

Self-portrait A. Zverev

A. Costakis P. Lobachevskaya Exhibit Zverev in Flames A. Costakis, N. Opaleva |

|

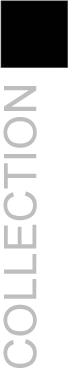

The AZ Museum's collection mostly consists of works from the collection of George Costakis (donated by Aliki Costakis), the collections of Alexander Rumnev and the Gabrichevsky family, and the private collection of Natalya Opaleva. Today, the museum has over 1,500 works by Anatoly Zverev and the artists of his circle. The museum's collection also includes archival documents connected with the life and work of Anatoly Zverev. The museum's collection is constantly expanded through the inclusion of new works that are subject to strict artistic review.

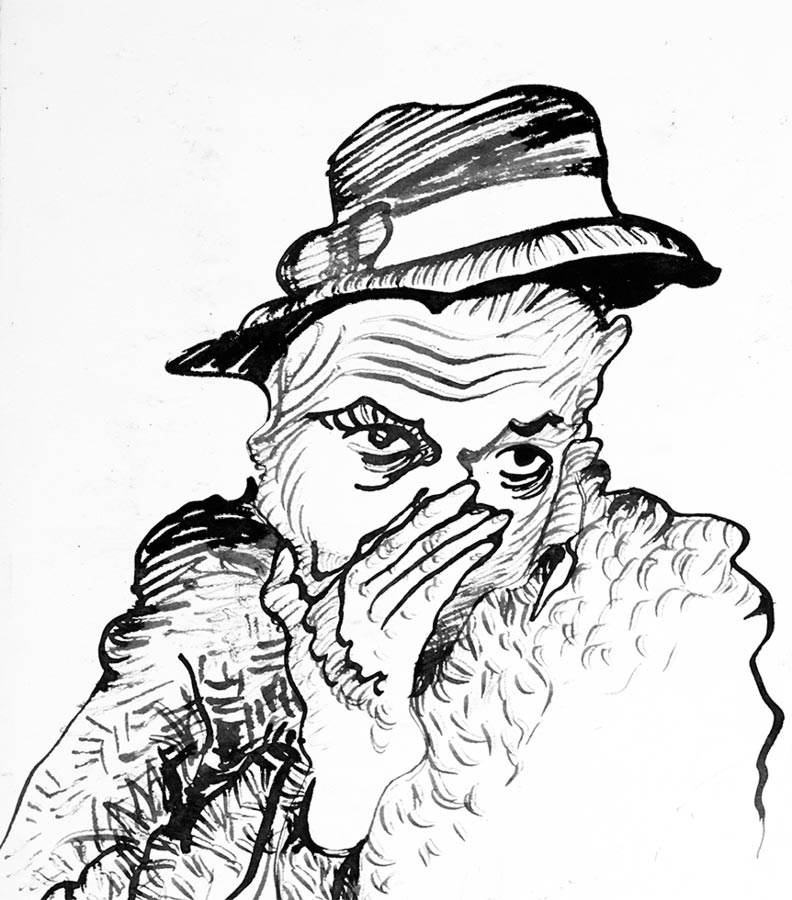

Portrait of P. Lobachevskaya

N. Volkova. Packing paintings in Greece A. Costakis, P. Lobachevskaya, Athens, 2012 Packing paintings |

|

Natalya Opaleva General Director and Publisher Polina Lobachevskaya Artistic Director and curator of exhibition and publishing projects Natalya Volkova Coordinator of exhibition and publishing projects, custodian Anatoly Golyshev Gennady Sinev Authors of the design project for the museum and exhibition, designers Alexander Dolgin Media artist Sergei Solovyev Editor of publishing projects  |

|

Our acknowledgments to: A. Costakis N. Costakis G. Apazidis I. Palmin V. Nemukhin O. Rabin O. Severtseva N. Shmelkova I. Kuznetsov M. Plavinskaya L. Pyatnitskaya J. Nosov A. Bakhmutskaya A. and N. Sinitsyn N. Vulfovich  |

|

N. Volkova, N. Costakis, P. Lobachevskaya, N.Opaleva

Exhibit Zverev in Flames Exhibit Zverev in Flames G. Sinev "Zverev in Flames"

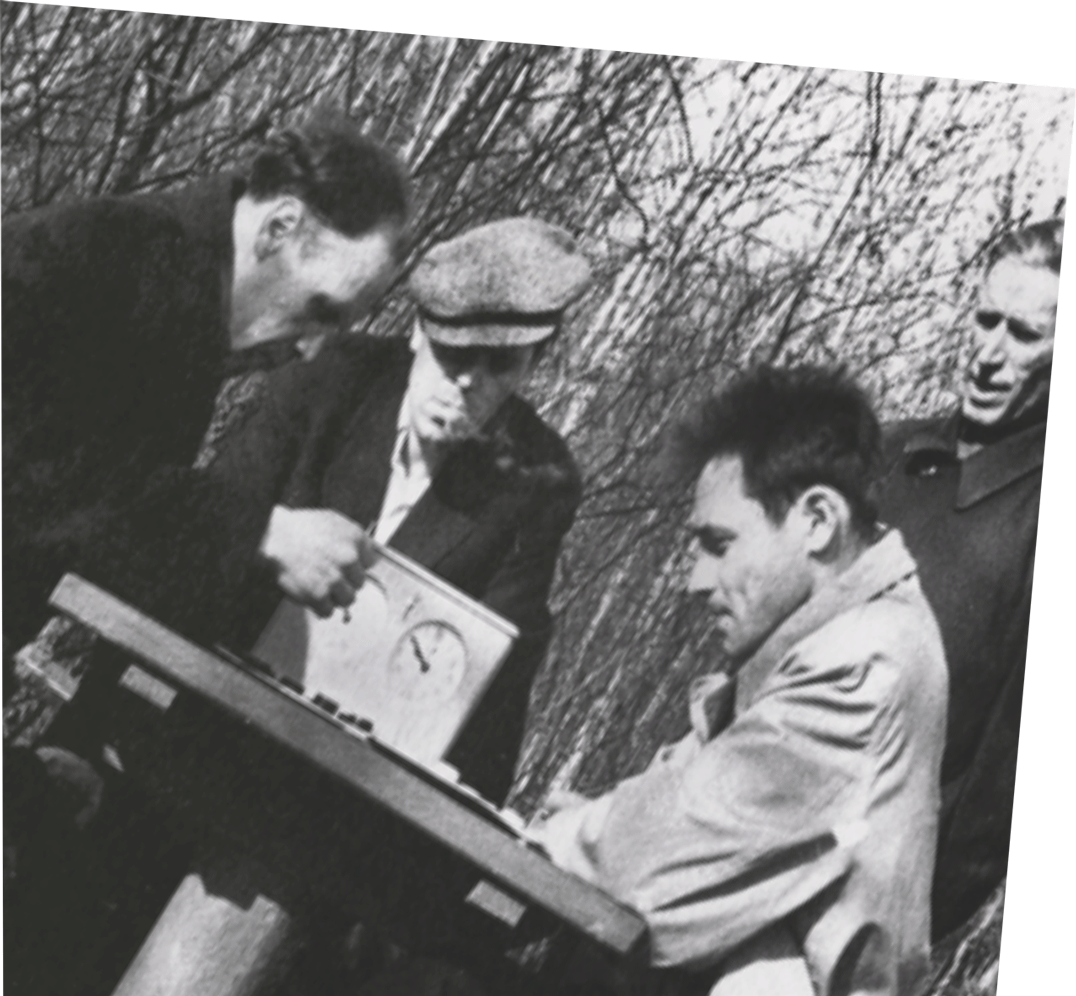

In June 2012, the exhibit Zverev in Flames opened at the New Manege. The rooms of the Manege were lit up with the glow of the old fire that burned down the dacha of the collector George Costakis in the village of Bakovka near Moscow. An enormous collection of artworks burned together with Costakis' house. Anatoly Zverev's worked survived the fire for an unexpected reason: their great number. The folder chock full of paper and drawings, which had become compressed over time, did not burn. The great number of Zverev's works (he was blamed for being "too prolific" during his lifetime and after his death) saved them from destruction. Scorched, charred and damaged by fire and water, these works were displayed at the exhibition.(New Manege, 2012) Over 30,000 visitors saw this collection of over 200 works. Nevertheless, their stunning discovery of Zverev's works that had not been shown up until then was not the only major event. Another event was the exhibition itself, from its idea to its implementation. The exhibit turned into a dramatic, passionate and futuristic space and into a state-of-the-art time machine that brought Zverev into the present and then catapulted him into the future – towards a totally new understanding of the artist.

Self-portrait

Female portrait Female portrait The Press about "Zverev in Flames"

Radio Svoboda, Lilia Palveleva: An exhibit with the intriguing name Zverev in Flames opened at the New Manege. It presents works by the leading nonconformist artist Anatoly Zverev that had been scorched by a fire in the house of collector George Costakis yet miraculously survived. The exhibit includes about 200 works by Anatoly Zverev. By a strange turn of fate, the jagged burnt edges have only made the drawings more expressive. Gazeta.ru, Arseny Shteyner: In recent times, Anatoly Zverev has begun to come to the attention of the public at large. At the current exhibit Zverev in Flames, Polina Lobachevskaya is presenting this brilliant and multisided artist that is far from the superficial image of the "painter of one theme". Polit.ru, Diana Machulina: The exhibit Zverev in Flames is wonderful insofar as puts Zverev's works themselves in the foreground. This exhibit has a superb design, although it may seem to be incompatible in its modernism with non-conformism. Yet how long can one show the Soviet underground in the same conditions as it existed at the time: surreptitiously, under the counter, attached with pins to the wall, and furtively? Indeed, there is no contradiction here: the design of the exhibit shows respect for the subject of the exhibit and helps viewers perceive the works with clarity. The design serves the purposes defamiliarization to help the viewer penetrate into the subject of the exhibit. The works resemble planets glimmering in the dark, and each planet has life on it – such is Zverev's universe. The technical perfection of the exhibit is inseparable from the project's content. We do not see any stands or walls: the black felt material turns them into the vacuum of interstellar space, while viewers do not see, remarkably enough, their reflections in the glass. Novye Izvestia, Sergei Solovyov: Zverev is an artist that is astonishingly modern, contemporary, multisided and still largely unknown. The exhibit's design is profoundly technological and futuristic. The "Fiery Room" that displays the main collection of extant drawings is particularly effective. The viewer walks down a red carpet through dark rows of glass stands where the scorched sheets shine like holograms. The same works appear highly magnified on screens where every dot and dash can be made out. Rembrandt himself is never shown with such care and esteem. Another room, the "Movie Theater", presents Zverev's brilliant self-portraits and films with recollections about the artist. Between them is a bright room with pictures from private collections that are connected in one way or another with the Costakis family. There is no Soviet historicism, eclectics or gallery tinsel: Zverev is presented as a European artist (it is no accident that Picasso greatly admired him), whose every brushstroke was precious, according to Falk. Kultura, Alexander Panov: The design is simply wonderful: from darkness through the white transparency of the Costakis memorial room and into the darkness of memory once again. The constructivist stands remind us that Zverev had initially wanted to be an avant-gardist (the remarkable Suprematist Studies of the late 1950s are evidence thereof). Zverev himself burned up in his work in the literal sense (this is what the exhibit is all about) and in the metaphoric sense. His early works, which were miraculously preserved and restored by Natalya Costakis and shown by Polina Lobachevskaya, confirm Pablo Picasso's description of Zverev as the "best Russian draftsman". In Russia, you have to live a long life to be appreciated. As soon as an artist dies, one finds unknown masterpieces of his – and makes a wonderfully beautiful exhibit. Vechernyaya Moskva, Asya Ivanova: Two of the three rooms making up the Manege are sunk into darkness. Pictures and drawings shine in the darkness. It seems as if nothing is lighting them up and that they are emitting a soft light themselves like the glimmer of a fire dying in the night. This is truly beautiful and enticing. The exhibit's solution is so precise, laconic and elegant and so perfect that you forget what ordinary drawings that have not been touched by fire look like. The scorched portraits and abstract compositions suddenly begin to lead a life of their own that is unthinkable without the deadly fire. The burnt edges seem to be not the result of barbarian destruction but a wonderful artistic invention that turns disparate paintings into a single mysterious series. |

N. Volkova, P. Lobachevskaya, A. Costakis, N. Opaleva

Exhibit Anatoly Zverev: On the Threshold of a New Museum Anatoly Zverev: On the Threshold of a New Museum

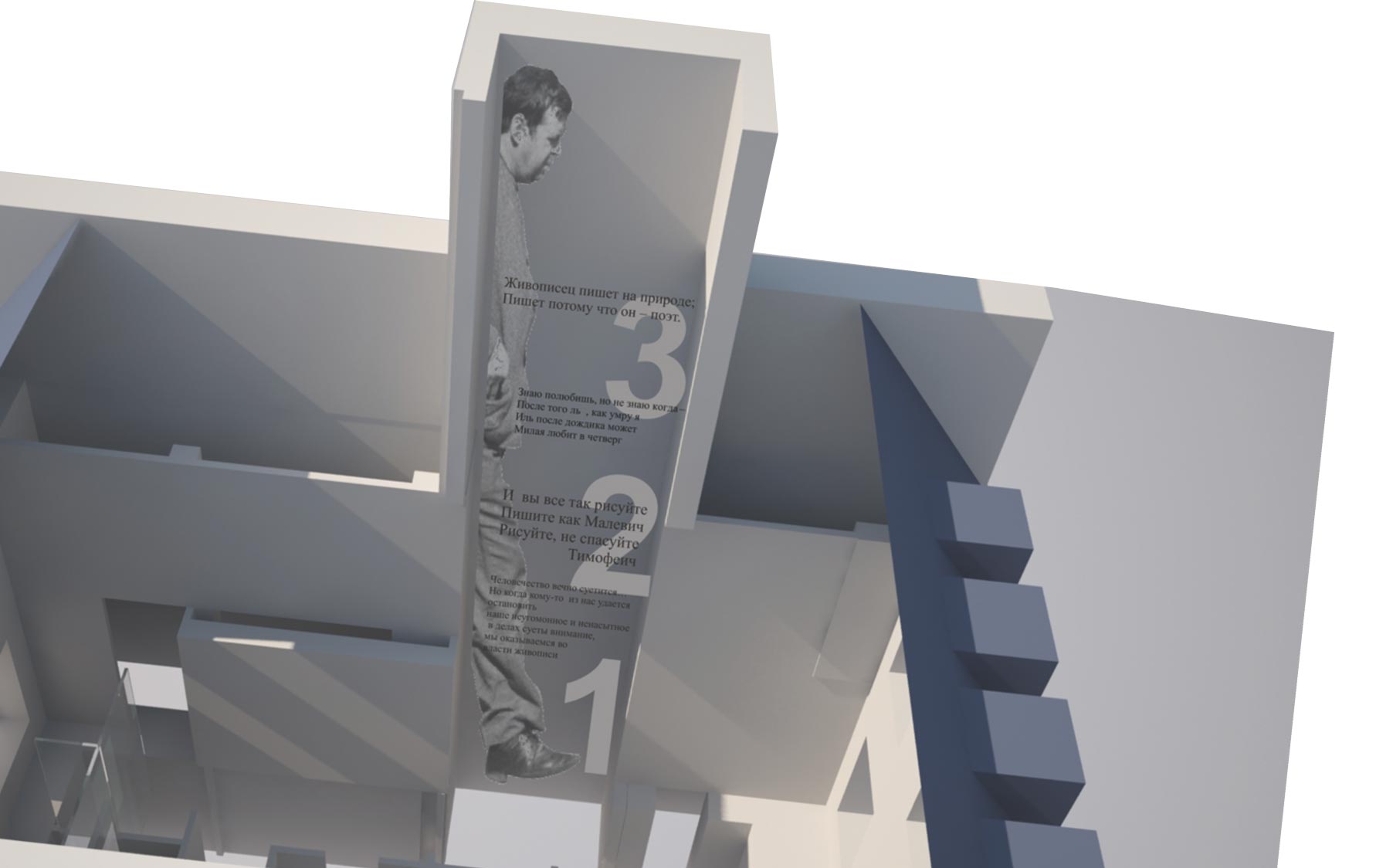

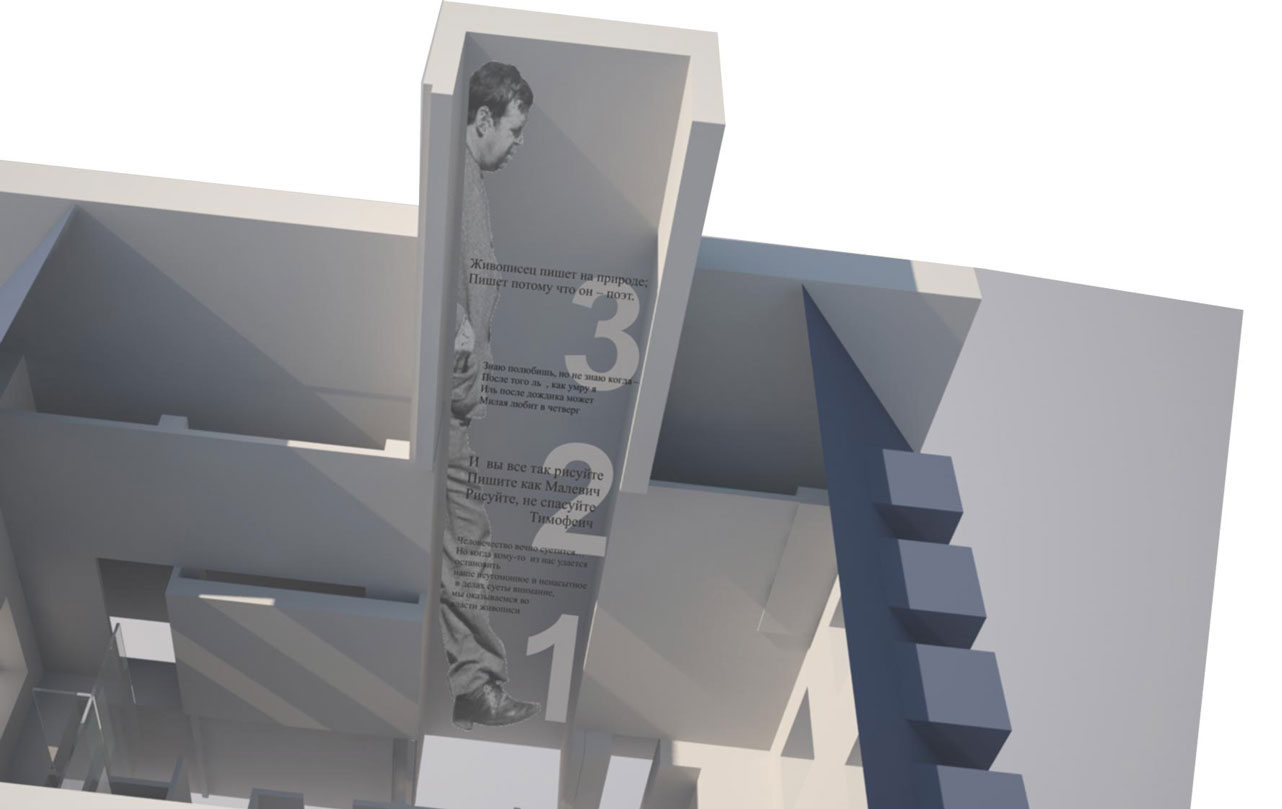

This exhibition presented the donation by Aliki Costakis, who gave a large number of Anatoly Zverev's works in Greece to the new AZ Museum in Moscow. The exhibit itself and its organization of space were used to try out the conception of the new museum, which began to become reality before one's very eyes.(New Manege, 2014) The museum's founders Natalya Opaleva and Polina Lobachevskaya presented Zverev in a very refined manner from a polyphonic and multisided standpoint. The exhibit showed all of Zverev's diversity as an artist, a person and a legend. The human and animal portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and abstract and suprematist works passed before the viewer in an endless stream of great artworks. The viewer also got to see Zverev in photographs, aphoristic sayings, documentary films and the descriptions of his contemporaries as a deep, sad and ironic person. The multimedia screens created the impression of a huge starry sky made up of Zverev's pictures. They made it possible to enlarge and diminish eyes, faces and figures in a couple of seconds. The constructivist design directly connected Zverev with the main movement of 20th-century artistic avant-garde, while the music of Sofia Gubaidulina that played softly in the background thrust him into the world of 21st-century art. The museum's large-scale publishing project, dedicated entirely to Zverev, gave the exhibit an encyclopedic aspect. The exhibit and the idea of the AZ Museum presented Zverev not simply as a painter and draftsman but also as a unique artistic phenomenon that accumulated numerous theories, practices, cultural models, philosophies, poetry, and prose and fused it all into a boundless personal universe.

The Press about the Exhibition:

Novaya Gazeta, Interview with Aliki Costakis: "One Must Exhibit Anatoly Zverev in a Worthy Fashion" - Your donation to the AZ Museum is unprecedented. It can only be compared with the donation that George Costakis made to the Tretyakov Gallery in his day. Could you briefly describe the collection of Anatoly Zverev's artworks that has returned to Moscow? - In a nutshell, they are Tolya Zverev's works that my dad George Costakis collected in the 1950s. The earliest dates from 1955 and the last works, if I'm not mistaken, from 1960. They include works painted with oil, a lot of works painted with gouache (Zverev's most common technique) and, of course, wonderful drawings. This collection consists of Zverev's works that remained in the Costakis family and that were mostly painted at our home. They range in genre from recognizable landscapes and self-portraits to unique abstract works. I should say that my dad particularly appreciated this period of Tolya's career. He greatly valued these works and showed them a lot to others. - In other words, they were displayed in a special place in your home so that guests could see them? - If you saw the walls of our Moscow apartment, you'd understand that there was no free space at all. When we lived on Leninsky Prospect, the walls in one room were totally covered by icons, and the walls in the other by avant-garde works. One picture by Popova even hung from the ceiling. I should say that my dad did not specially collect the artists of the sixties. He associated with them, liked them personally, and supported them, while they gave him their works as gifts. Yet he didn't have such a collector's passion for their art as he did for the avant-garde. At the same time, he singled out Tolya Zverev among all the artists he knew. I would even make such a comparison: the love for a woman is different from the love for a child. My dad felt a deep and almost fatherly feeling towards Tolya. He tried to show and promote his work at every occasion: he would put an easel in front of guests and show Zverev's works on it one after the other. He gave quite a few works as gifts – not because he didn't like them but because he hoped that others would take an interest, too. - The fact that Costakis singled out Zverev among all other contemporary artists is very significant. Are you sure about that? - Absolutely. My dad liked and appreciated many artists. His collection included Tselkov, Plavinsky, Belenok, Sveshnikov, Rabin and others. I can cite a lot more names, all the more as I still keep in touch with all of these artists (those that are still alive). For him, they were all wonderful people… Yet Tolya was number one. He was his Van Gogh. My dad totally believed in it. He considered Zverev to be the greatest genius among the non-conformists. He believed that Zverev stood head and shoulders above the rest. - Isn't it paradoxical? Costakis' passion for the avant-garde, on the one hand, and his love for Zverev, on the other. After all, Zverev is a realist (at most, an expressionist) for the layman. You can't put him next to Malevich, say… - This is a superficial and erroneous view. Tolya Zverev's art did not stem from realism (and even less from socialist realism). You had to see how he painted. I saw how he worked. There were a lot of cans, brushes and paper on the floor. Zverev scattered paint, and drops à la Pollock appeared. It was witchcraft of sorts. And you never knew how the final brushstrokes suddenly made the eyes and then the entire image appear. We could not understand how it all happened. I believe that he had a gift of intuition. How can one call him a realist? He painted uncontrolled spots, and the result was a brilliant portrait or self-portrait. And have you seen his suprematist works? And his drawings? I once saw a huge Matisse exhibit at the MOMA. God forgive me, but I would say that Zverev drew just as well as Matisse or even better. He produced such masterpieces that other artists could never make no matter how hard they tried. And he did it all with a single line! - Wouldn't you say that Zverev himself is also responsible for the fact that people have tended to underrate him? It's hard to imagine him as a respectable and established artist… - There are learned artists that begin to think about strategies and conceptions already in their youth. As to Zverev, dad said about him (in a coarse though very exact manner), 'He does everything from his guts.' By the way, dad could say the same thing about a brilliant musician or actor. He meant that Tolya did not invent anything or think anything out ahead of time. Some 'respectable' artists think about what they should do to appeal to people. Tolya worked as he breathed. It was almost something biological, like eating and drinking. I don't remember hearing dad and Tolya discuss other artists or paintings. Despite his constant joking and carnival antics, Tolya was an introverted and solitary person. He preferred to joke or say nonsense to hide his pain and sensitivity. Just read his poems and "treatises"… They are all irony and self-irony. Nevertheless, one senses the power of thought behind them. For him, joking was self-protection – a kind of armor.

A.Costacis, S. Solovyov

G. Coatakis, A. Zverev G. Costakis with wife and daughters - In other words, his genius always shined through in any case? - I'd say more: he wasn't just a brilliant artist but he was also a person with his head in the clouds. Dad called him Van Gogh without any irony. Just recall Tolya's unrequited loves, unsettledness, and lack of recognition during his lifetime… I simply can't imagine Zverev sitting down and seriously talking with my dad about shoes that he had to buy in time for winter, about selling paintings and about organizing exhibits. God forbid! I had never heard it and could not have heard it. - Is it true that Zverev took an interest in you at one point and even asked for your hand? - Dad wrote in his book about how Zverev asked for my hand. To tell the truth, I had known nothing about it at the time. The only evidence of his 'interest' was 57 portraits that he painted in a single day (I was 18 at the time). They were all lying on the floor. Naturally, I didn't pose for him. I could simply wash the dishes or make sandwiches for guests in my usual manner. He painted covertly. He seized the images instantaneously. None of the portraits resemble each other, although all of them depict me. There is a stunning work where he unexpectedly depicted himself next to my portrait. I call it "With Saskia". Zverev never painted anything of the sort again. Such a work is priceless, of course, and it belongs in a museum, not in a private collection. - How do you feel about giving Zverev's works away? Don't you feel sorry somewhere inside about parting with them? - I'm giving them away with an easy mind – just as my father gave away his avant-garde collection. I'm making this gift in memory of my dad and Tolya. After all, I can hardly hang Zverev's works in my apartment in Athens and invite people over so that they finally discover this great artist. Tolya Zverev deserves to be exhibited properly and to be shown in all his might. It may be bold of me to say that the works in the Costakis collection stem from Zverev's best period. Nevertheless, I know from experience that artworks of such quality are extremely rare. - Do you believe that the new Anatoly Zverev Museum is apt and likely to be successful? - Truth be told, I have tried to demonstrate the great value and importance of our collection for a very long time. When we left in 1977, we were allowed to take Zverev even without an inventory: it was simply written '7 folders of Zverev'. It should be said that, in those days, the Tretyakov Gallery took even early 20th-century works with hesitation. As to Zverev's works, they simply gave them to us to be out of harm's way. And it's no surprise that there are many gaps in good mid-20th century art in Russia today: official museums have never collected or paid attention to it. After my father's death, we organized a good exhibit of Zverev's works in Göttingen in Germany upon the recommendation of Savva Yamshchikov. It included precisely those works that have now come to Moscow. I saw at that time what a strong reaction they evoke and how important and modern they are. By the way, I have always had a feeling of guilt that we have hidden, in a way, these extremely interesting works by Zverev. We hid them without even wanting to do so, opening the way to the circulation of forgeries and run-of-the-mill works. I once proposed to the Museum of Private Collections (a subsidiary of the Pushkin State Fine Arts Museum) that we should show some good Zverev. After all, selection is very important for any artist. Yet they didn't show any interest. When Polina Lobachevskaya and Natalya Opaleva visited me and told me about their desire to create a new museum, we immediately understood each other, literally from first sight. I believed them that they were interested in showing real art and that they were not thinking in market terms. After all, my father did not collect art in order to invest money. (Present-day rich 'collectors' tend to associate with art critics in order to understand what will bring a profit and what won't.) In contrast, my father had a flaming soul. You have to see with your soul. I immediately sensed that the creators of the Zverev Museum had the same quality. We didn't engage in any long talks or explanations. Everything took place instantaneously. It was as if we had discussed it for a long time and had reached a common decision: Zverev should return to Moscow and should be exhibited in a worthy fashion. Interview by Sergei Solovyov |

|

| Medved Magazine:

The exhibition project Anatoly Zverev: On the Threshold of a New Museum is another step in the long, painstaking and selfless process of creating a unique Moscow museum of the work of Anatoly Zverev, one of the most remarkable artists of the 20th century. The ideologist and driving force behind this noble initiative is the Polina Lobachevskaya Gallery. In cooperation with colleagues and with the support of Natalya Opaleva, it was able to gather a full-fledged monographic collection consisting of original works, archival documents, and rare books, to organize effective scholarly work, and to assure a professional approach to storage and restoration. The exhibit shall present about 300 paintings and drawings dating from 1957-1960, one of the best periods of Zverev's work. Anatoly Zverev's artistic heritage can hardly be overestimated. Thus the project designers attached particular importance to the exposition. In the rooms of the New Manege, the exhibit Anatoly Zverev: On the Threshold of a New Museum develops powerfully and effectively, involving the viewer in the museum laboratory where great artistic discoveries are made: the project of the future AZ Museum building, its wonderful collections, and the latest acquisitions that are unknown even to specialists. The multimedia installation unites the exposition space and reveals the depth and scale of its conception, which corresponds to the artist's expressive lyricism. Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Zhanna Vasilyeva: The present exhibition is a sensation insofar as the public is able for the first time ever to see Zverev's early works of the 1950s and 1960s from the collection of George Costakis. His daughter Aliki Costakis donated these works of Anatoly Zverev (whom her father seriously called the "new Van Gogh") to the AZ Museum. At the New Manege, these gouaches with scorched edges, landscapes, portraits and animal depictions (which could also be called animal portraits, as Zverev reveals the individual and very expressive nature of each cat, dog and crow) are exhibited in the semidarkness and lit up with diffuse lighting. Four documentaries about the artist are shown in a small screening room behind a round stand covered with the posters of the 1984 Moscow exhibit. These films and especially the very inventive and precise documentary Sit Down, Kid, I'll Immortalize You do more than just introduce viewers to the living Zverev, who is homeless like Chekhov's Kashtanka, "hapless" (as Zverev called himself) and incredibly gifted as an artist. They also show the remarkably cinematographic nature of his work. This refers not only to the artistry with which he made his works, managing to turn almost everything (even cooked beets and vegetable oil) into paint or an artist's tool. Above all, it refers to the fact that Zverev's drawings, gouaches and landscapes painted with oil became instantaneous snapshots of intonations and moods even more than of external appearances. Strangely enough, this instantaneity, mobility and changeability of the image did not result in vagueness. In contrast, a gaze, gesture or image could suddenly appear out of the apparently random spots, lines and dots. Zverev was interested not by the deconstruction of form or the expressiveness of abstraction but by the appearance or emergence of the image from the non-being represented by the blank piece of paper. Novye Izvestia, Sergei Solovyov: The exhibit in the New Manege, which is designed to present the future Anatoly Zverev Museum, is based on paradoxes: ironic quotations from the artist's writings instead of labels, two years of intense creative work instead of a long biography (Zverev's works of the late fifties are exhibited here), and complicated constructions showing works in unexpected perspectives instead of a solemn exposition. In other words, it is an art project rather than a memorial. Like Don Quixote (Zverev's beloved character), project curator and initiator Polina Lobachevskaya is tirelessly struggling with museum windmills grinding feelings and emotions. The exclamation of admiration and the emotional shock are the most important for her. In the New Manege, viewers experience such a big shock that they wonder at first whether they have come to the right place. Expecting to see another "apartment exhibit" of a Russian artist that fell by the wayside of 20th-century styles and movements, they find themselves at the show of a Western artistic star with all the attributes of an expensive multimedia show. In the Manege exhibit, one is particularly struck by how forward-looking Zverev was. In the space of only two years, he created a series of works that would have taken other artists an entire lifetime to make: from tachist portraits and virtuoso animal depictions to suprematist paintings, from Matisse nudes to innovative illustrations to literary classics. None of the sheets of paper or cardboard shows signs of a novice's imitation or conformity to norms. The appearance of such a free artist in the post-war Soviet Union remains another paradox and mystery of Zverev's biography. Here one sees everything from the most radical performances (which Zverev made during his "painting sessions") to totally classical works. If the founders of the AZ Museum retain their enthusiasm for the remainder of the year (the museum building on Tverskaya-Yamskaya Street is scheduled to open in late 2014), we shall witness a new age of cultural creation. An artistic establishment of such level and quality has not appeared in Moscow since the days when Tsvetayev gave the tsar and the country the present-day Pushkin Museum. Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Darya Kurdyukova: The designer transformation of museum rooms implemented by Anatoly Golyshev and Gennady Sinev is a prototype of how Opaleva and Lobachevskaya see the future museum. It should be as modern as Zverev himself (the publishing program is in full gear already, and visitors can look through its publications or watch films about the artist). It must not be boring, and so straight spatial enclosures, including traditional walls, glass, and even lattice gratings out of which beams emerge and light up portraits (Zverev's beloved female portraits alternate with self-portraits), landscapes, nudes and sketches of animals give way to red curved designs in the spaces containing Zverev's personal version of suprematism. His pictures move along the screens, separating and reassembling like cards in solitaire. He could trace lines (although he did not like to make long ones), he could assemble (if one can use such a word for this Russian equivalent of Jackson Pollock) a fully finished landscape out of color patches, and he could create a color mess. He would make a couple of touches here and there, and suddenly the brushstrokes, blots, and drops would combine into the eyes of a new image. Light alternates with darkness, and well-preserved works are interspersed with works scorched by fire. In 1976, Costakis' dacha in Bakovka burned down, and a considerable part of his collection of sixties artists was destroyed. Zverev's pictures survived, because they were stored in folders, where they had been pressed together over time. Only the edges were scorched. They resemble a metaphor of time: black & white and color faces, figures, and landscapes seem to look out of windows in their scorched frames. Zverev himself runs over his works and the modern technical effects: a broad strip showing his words stretches through all three rooms. He also appears himself in two stages: his long gait, followed by the upper part of his body. This, too, is all about time: he is either abreast or ahead of it, and we must catch up with him. Moskovsky Komsomolets, Maria Moskvicheva: A colorful and stylish rehearsal of the future Anatoly Zverev Museum is being held at the New Manege. About 250 works by Zverev hang on the dark walls; all of them were made in 1957-1960, one of his most productive artistic periods. At that time, Zverev with his image of a drunk and disheveled vagabond suddenly emerged as the leader of Russian non-conformism and the living incarnation of free and unfettered art. The opening of the exhibition, which shall present the collection of Anatoly Zverev's works gathered by George Costakis, is a long-awaited event. After all, Zverev is a figure surrounded by many astonishing and wild myths, while his works strike the viewer with their lightness and emotionality. Vedomosti, Olga Kabanova: The new exhibit at the Manege introduces the public to the AZ or Anatoly Zverev Museum that is scheduled to open in the near future. This private museum shall stand out through the active use of stylish exposition design: the theatrical organization of space, the elegantly presented aphorisms of this sharp-tongued artist, alternating video projections of works, and effective lighting. Here visitors are also introduced to the results of the publishing program: several books about the artist, books with his illustrations and four documentaries. Naturally, one is looking forward to the opening of the AZ Museum.

Tribuna, Antonina Kryukova: "I simply depict things: I depict snow and become snow, I depict a cloud and become the cloud." These words of Anatoly Zverev explain the charm and naturalness of his unique artistic style. A solitary house with lit-up windows, a tilting birch tree, an autumn tree in the tumult of multicolored leaves, a bright church and an abandoned cemetery: all of this is familiar and dear to every person that feels himself to be part of the space depicted on Zverev's paintings. "The painter paints from nature, paints, because he's a poet." He was a subtle poet and a homeless wanderer that absorbed the surrounding world into his imagination and reflected it in paints, lines, and light brushstrokes. He fused them into tender images of falling snow, pink sunsets, large-eyed women and birds soaring in the air. He, too, was a bird that experienced the freedom of flight. Despite their bright colors, Zverev's numerous female portraits portraying different people are not as simple as they may seem. They are striking not in their similarities but in their depth and the very essence of being that is often rootless and tragic, almost desperate. Yet isn't this the real drama of life, which we should recall at least occasionally so as not to succumb to passing temptations? "Art is free; life is constrained," said Zverev, who had neither paints nor canvases nor a home and knew neither comfort nor prosperity. How Anatoly Zverev saw himself can be seen from the lines running across the monitor in the New Manege: "Awakened and gloomy, happy and tipsy, without joy, without freedom, without life and with being." Yet this self-description is far from exhaustive and is supplemented by other epithets (that can be continued, too) on another monitor: "Pensive, forgetful, lost, expended, intimidated, humiliated, exalted, diligent, papery, exuberant, and debased with a bit of the excessive, the reduced and the crazy." Literaturnaya Gazeta, Arina Abrosimova: The exhibit has several surprises in store. Few people know that Zverev worked in the genre of suprematism and wrote poetry. His recently found graphic illustrations are also a discovery. The AZ Museum Publishing Project presents books of Russian and world classical literature illustrated by Anatoly Zverev: The Gogol Cycle (Viy, Taras Bulba, and The Lost Letter), H.C. Andersen's fairy tales (The Nightingale, The King's New Dress, The Swineherd, The Mermaid, and Wild Swans), and Lucius Apuleius' Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass. The 100 Self-Portraits has also been published as a separate book ("Try to depict yourself in different positions and moods, and this will also nourish your philosophy"), along with Zverev in Love, a very unusual book in portraits, photos and poems that tell about the seventeen-year relations between the artist and his muse Oksana Aseyeva, who was the poet Nikolai Aseyev's widow, the former beloved of Velimir Khlebnikov and a friend of Mayakovsky, Burlyuk and Pasternak from her youth. The exhibit, which consists of 15 sections, will also delight visitors with a video installation that brings the master's work to life. You've just got to sit down and enjoy: "Mankind is always bustling… Yet when one of us manages to freeze our attention that is bustling so restlessly and insatiably in vain things, we find ourselves in the domain of painting." Artguide: Anatoly Zverev is the incarnation of the image of a true contemporary artist that does not evoke the resentment of the public at large. A homeless alcoholic, charismatic and madman, Zverev painted on anything that was at hand. His tragic fate made his genius indisputable for history. There appeared volunteers that initiated the creation of his museum: the curator Polina Lobachevskaya and the collector Natalya Opaleva. The exhibit at the New Manege is a rehearsal of the new museum's exposition. Zverev's works are brought together in a multimedia installation in order to show a Zverev "that no one has ever seen" (although this is dubious praise, given the large number of forgeries): "non-hackneyed, anti-museum, and extremely avant-garde". Vash Dosug, Sergei Solovyov: Any (even the tiniest) work by Zverev can be magnified by a factor of 100, cropped and "animated"… His works are full of interactivity and the energy of motion. All of this suggests that one should expose them in a totally new and unusual manner. Polina Lobachevskaya together with the designers Gennady Sinev and Anatoly Golyshev managed to employ the Zverev impulse to the utmost extent. | |

FROM VISITORS' BOOKS (1958-2014):

Tolya!

POSTHUMOUS EXHIBITS

I'm delighted that the inhabitants of Leningrad could finally see and appreciate this exhibit. I have known his work for a long time, and I've always regretted that such a unique talent with a very subtle worldview and psychologism is uninteresting to many people. All-pervading energy, power and magnetic appeal emanate from his paintings. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

A. Zverev is a genius. One sees this in his diffuse and simultaneously concrete world, in his vehemence and simultaneous inner peace, and in his frenzied tenderness.

A great Russian artist. "We don't cherish what we have yet cry when we lose it…" What a shame for the country: we've killed an artist with a very big heart.

It's now clear why Zverev was prohibited. His works are sermons of purity and freedom.

Such an exhibit should become permanent, and one should take young artists to see it. It should be mandatory for anyone who wants to become an artist. |

|

| «SIT DOWN, KID, I'LL IMMORTALIZE YOU!»

P. LOBACHEVSKAYA GALLERY AND CHEKHOV HOUSE EXHIBITION HALL, 2009 A major event in Russian cultural life… A tragic fate and such talent! When will Russia finally begin to appreciate talented people during their lifetimes…?! Thank you for the exhibit, for the atmosphere of the sixties and seventies and for the preservation of the culture of that time. Yet one wants more: such important elements of our culture should be studied, transmitted and stored… For example, that a Zverev museum should be established in Moscow. Thank you that you reminded us of our humanity through your exhibit. Meetings with Zverev are so rare! And thus each one is priceless. Yet your exhibit is unique: I sit here, look, listen… and I don't want to leave. Thank you for having invented and implemented something that is worthy of his genius. Thank you very much for such a striking and emotional exhibit! A great artist with an extraordinary artistic temperament! I got a lot of pleasure from your project and hope that there will be a sequel. «ZVEREV IN FLAMES» NEW MANEGE, 2012 For anyone who doesn't know Zverev's name, it will be totally clear that he's a genius. Everyone that knew his name will now want (after such an exhibit!) that a Zverev museum open in Moscow! I came to the exhibit with my 11-year-old granddaughter. I told her, "If you don't see Zverev now, you'll never see him again!" This exhibit is wonderful! One rarely gets to see something of the sort. Zverev is, of course, a genius and a great artist that we still probably don’t understand very well. He deserves respect, admiration, books, monographs, exhibits… and a MUSEUM. G. Mednikova and I. Yashina A Zverev museum should be established in Sviblovo, where he lived! Vladimir Volkov That's right! One must open a museum and a monument to Zverev in the center of Moscow! What a genius! A great artist and human being! Your exhibit, Polina Lobachevskaya, is a priceless cultural phenomenon and a great gift to our inner worlds and to the love and faith in each of us. We hope to see the Zverev Museum as soon as possible, as it is essential to the life of our Culture. Irina Myaskovskaya, art critic |

|