|

|

|

AZ MUSEUM

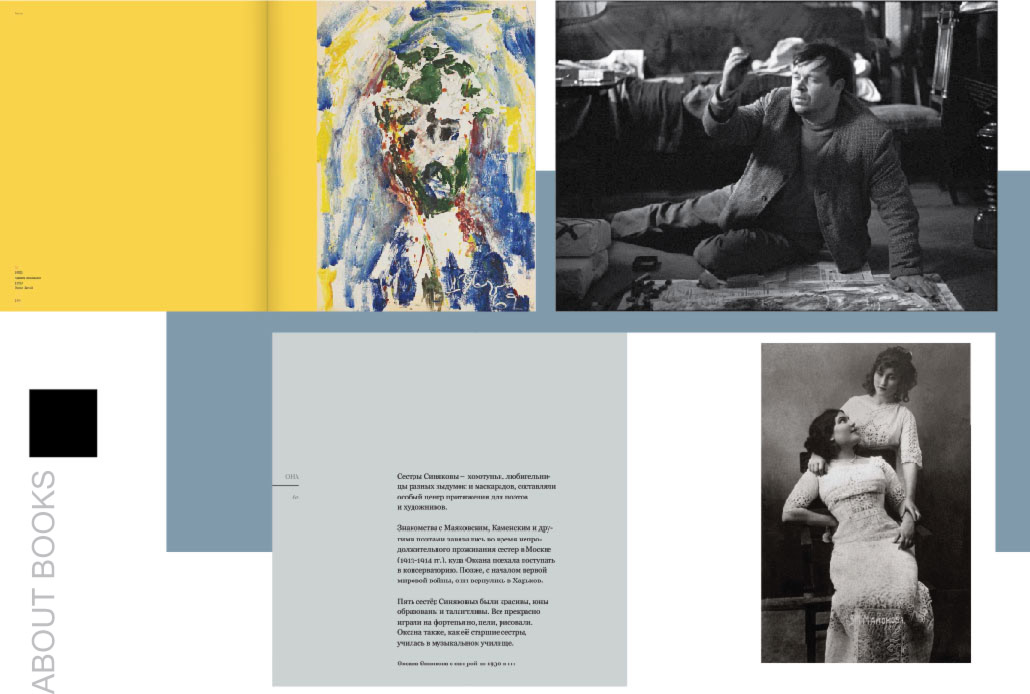

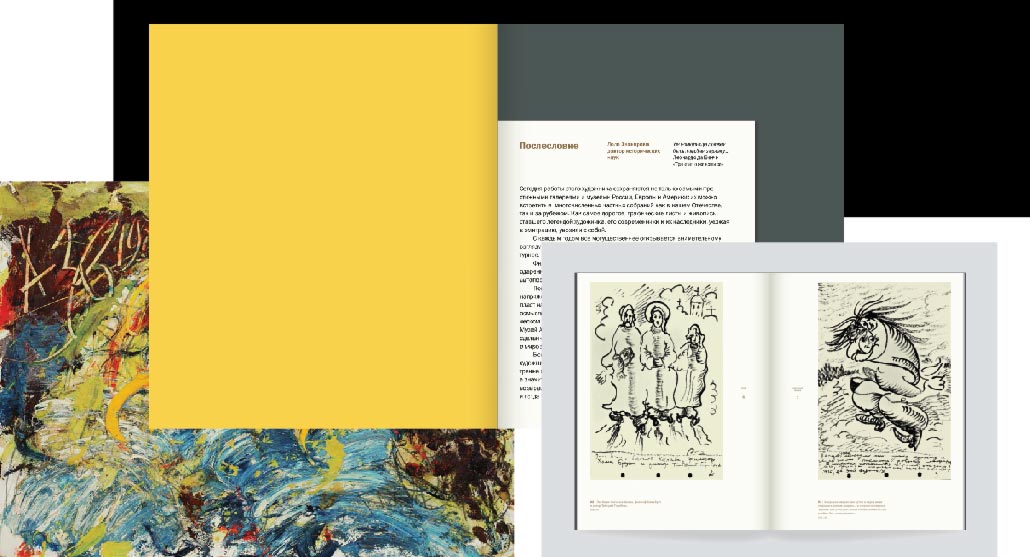

PUBLISHING PROJECT The AZ Museum is presenting unique art projects in its publications. The art books that have been published with the logotype "AZ" are more than just illustrated books. They are an artistic laboratory and a testing ground where similar problems arise as during the creation of full-fledged exhibits. It is more than just a matter of finding, selecting and interpreting rare materials connected with Anatoly Zverev's life and work. In its curatorial and design image, each book tries to imitate the inventiveness and many-sidedness of its hero. For the first publications, the editors chose those themes and subject matters of Zverev's enormous heritage that are particularly interesting for present-day viewers and the least known even to specialists.

The AZ Museum Publishing Project became yet another incarnation of Zverev as an artist and a human being, changed people's views about his work, and gave a new hold on life to Zverev in all his diversity and profundity.

|

|

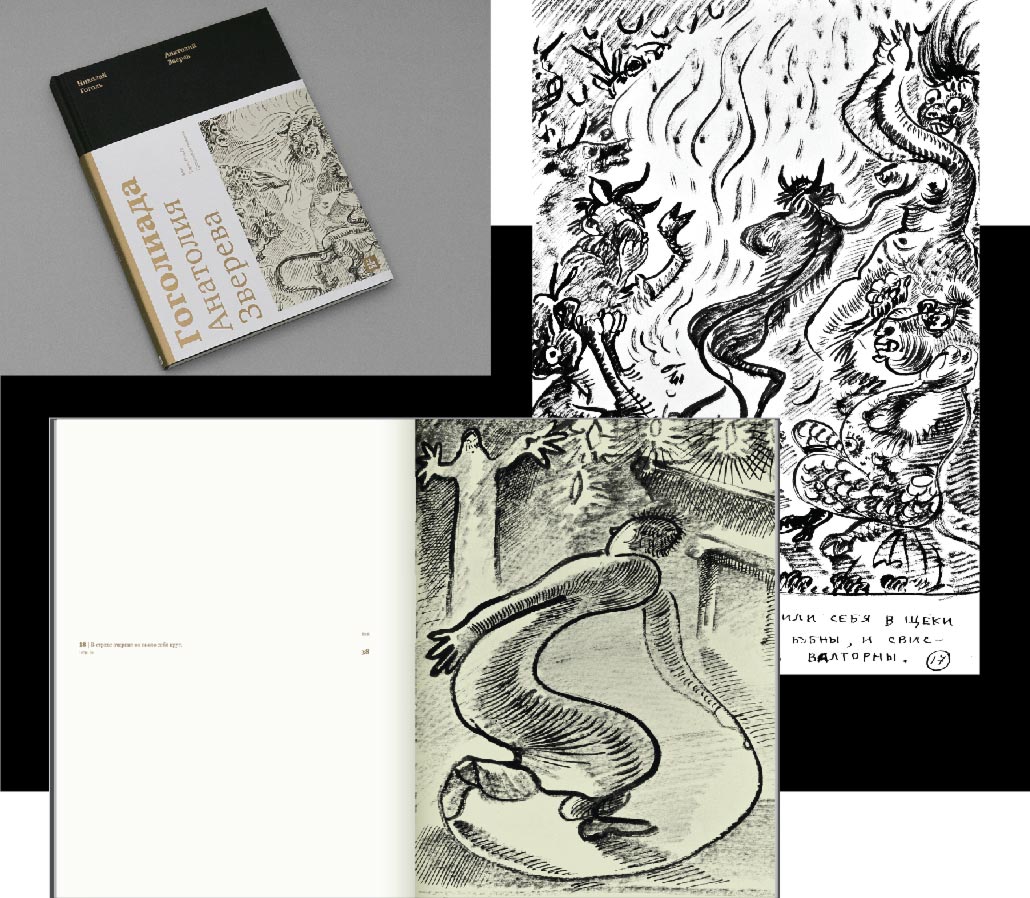

Anatoly Zverev's illustrations to Russian and foreign classical works of literature (Apuleius, Gogol and Andersen) were hidden for decades in archives and private collections. The innovation and boldness with which Zverev "exploded" the customary framework of illustration can be fully appreciated only today in the age of avant-garde perspectives and the "clip mentality".

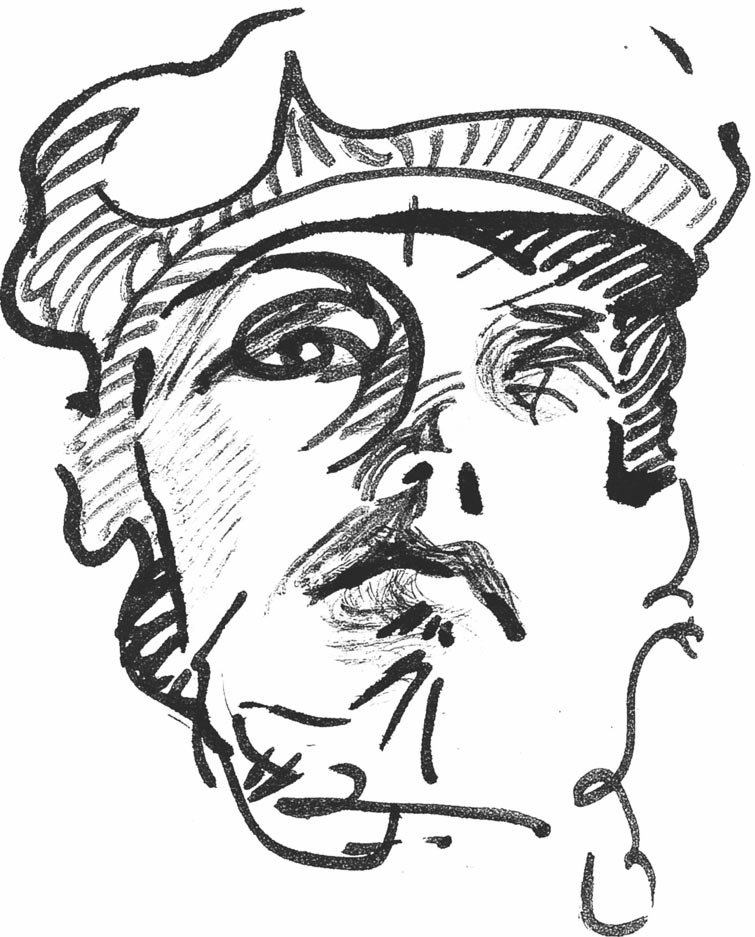

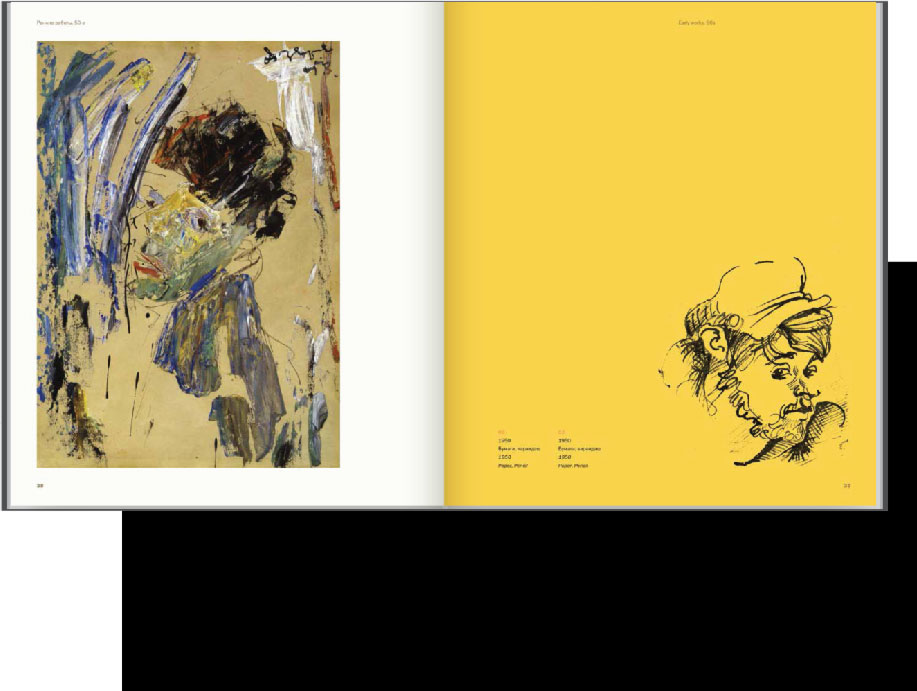

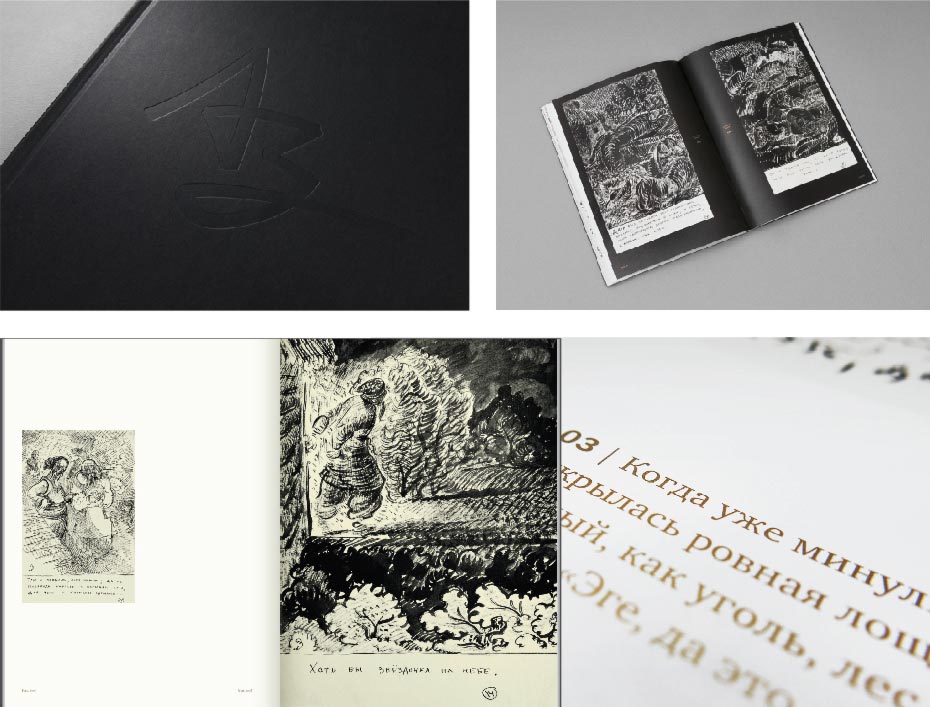

«Anatoly Zverev's Gogol Cycle»

These are the most expressive illustrations to Gogol's short stories (Viy, Taras Bulba, and The Lost Letter) in the history of Russian art. Zverev's favorite writer inspired him to make one of his most impressive cycles of drawings that was done "in a whirlwind of admiration and horror", to cite Igor Zolotussky.

|

|

|

|

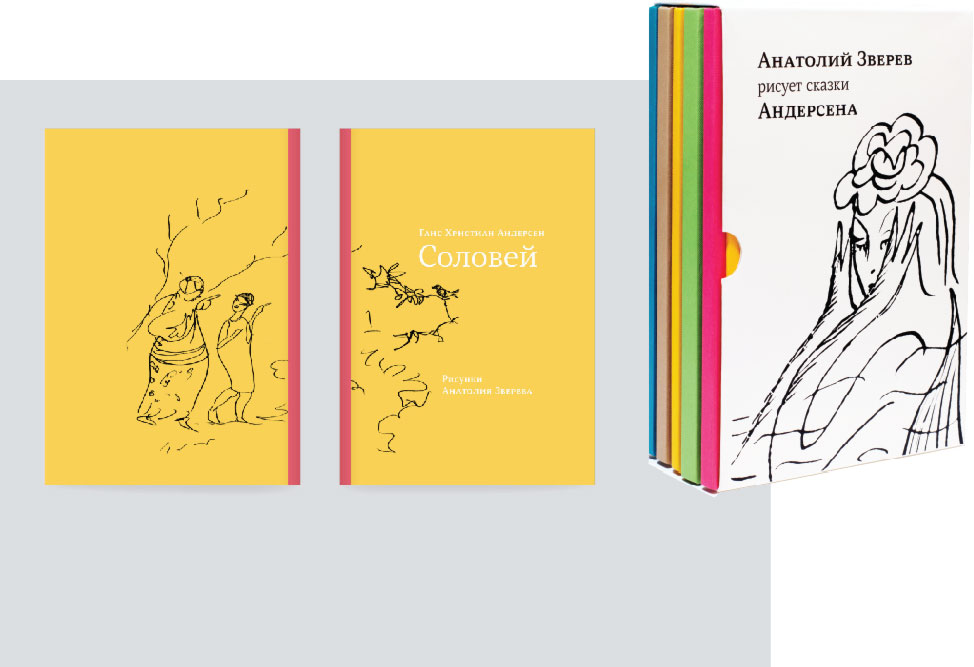

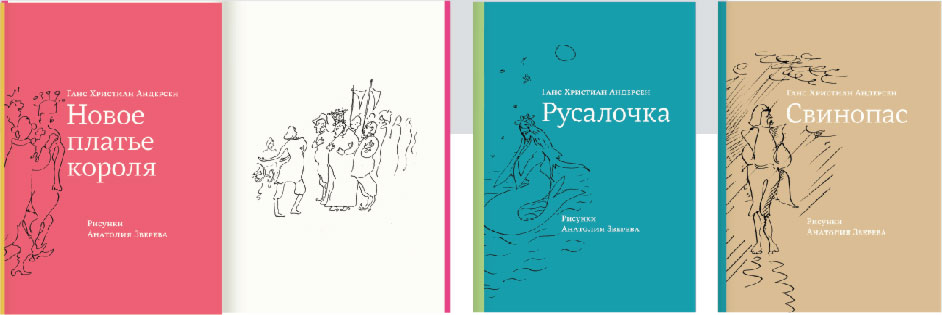

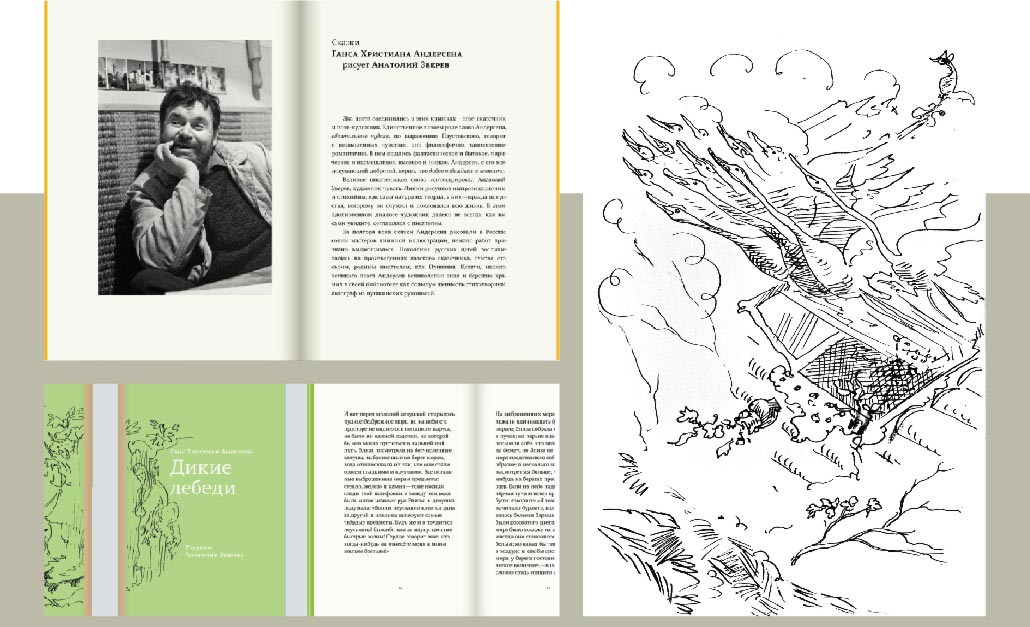

«ANATOLY ZVEREV

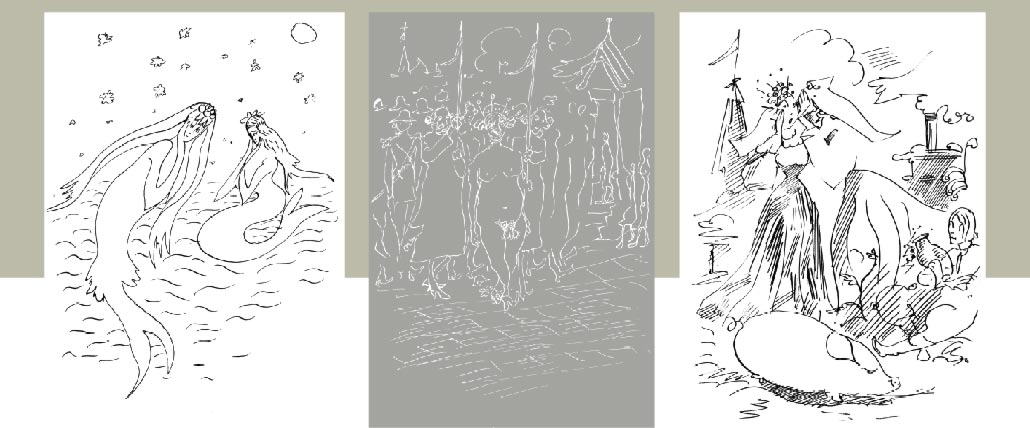

ILLUSTRATES ANDERSEN'S FAIRY TALES» Zverev's virtuoso illustrations to five Andersen fairy tales

(The Nightingale, The King's New Dress, The Swineherd, The Mermaid and Wild Geese). According to leading specialists, these drawings number among the best illustrations that have ever been made to Andersen's work. |

|

|

|

|

|

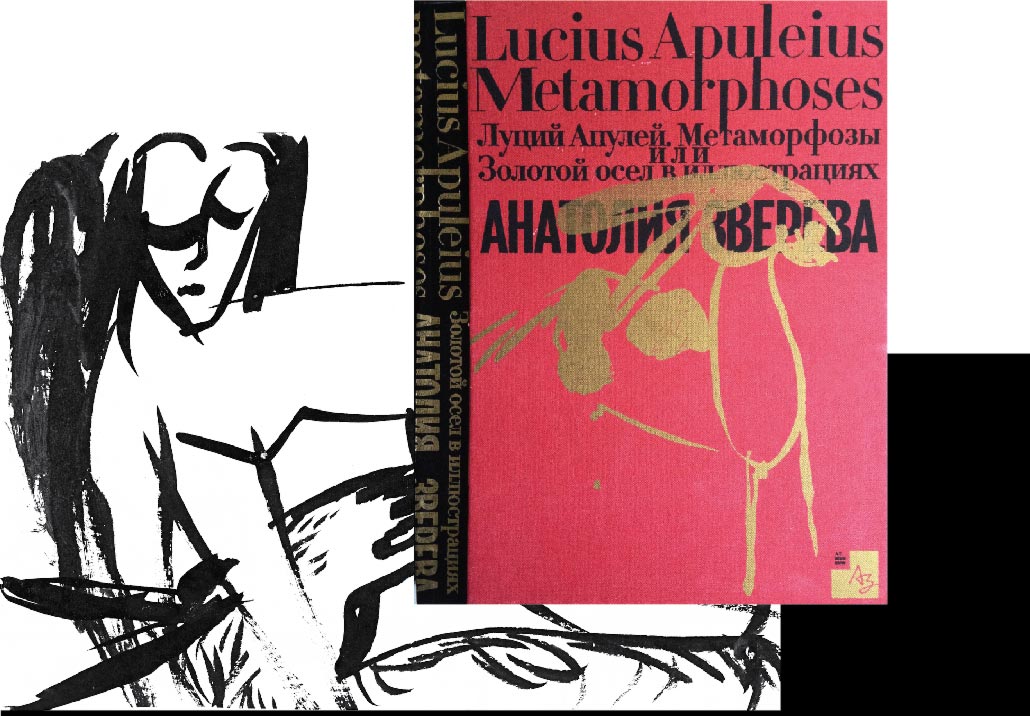

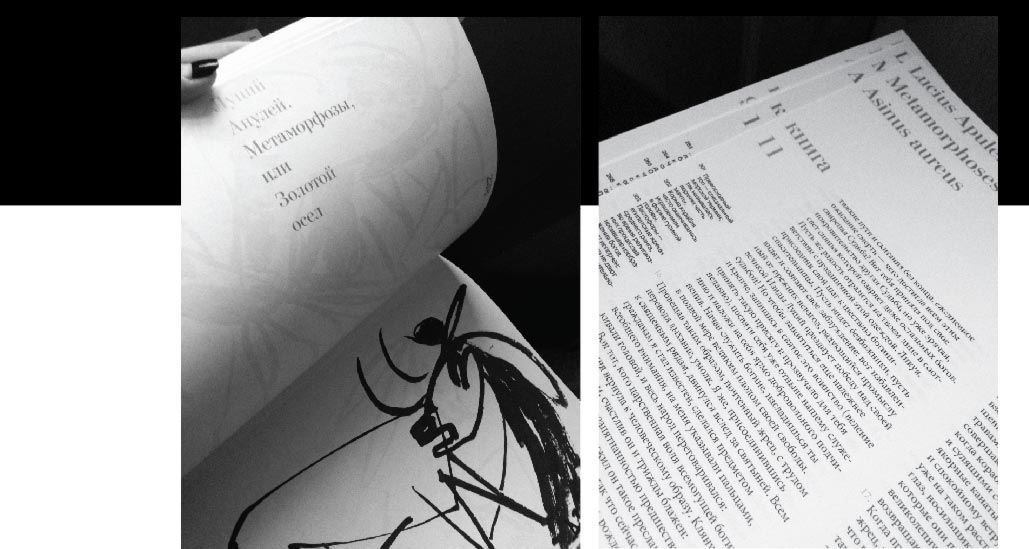

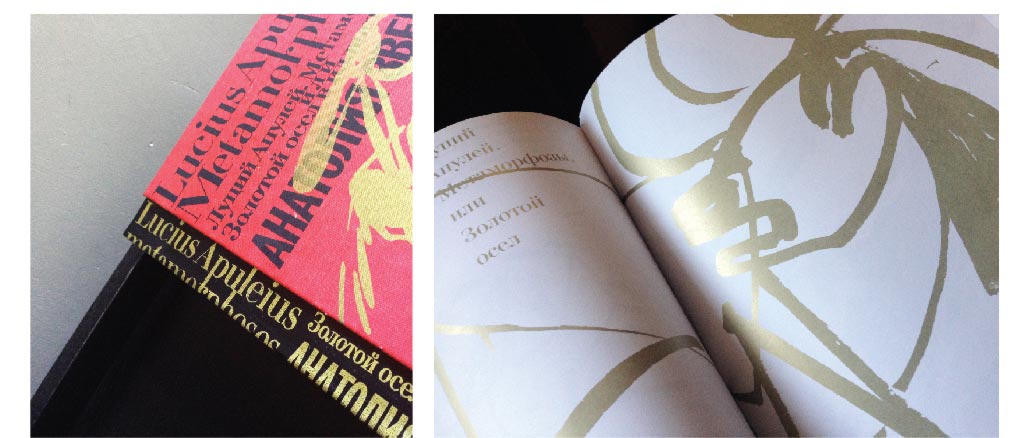

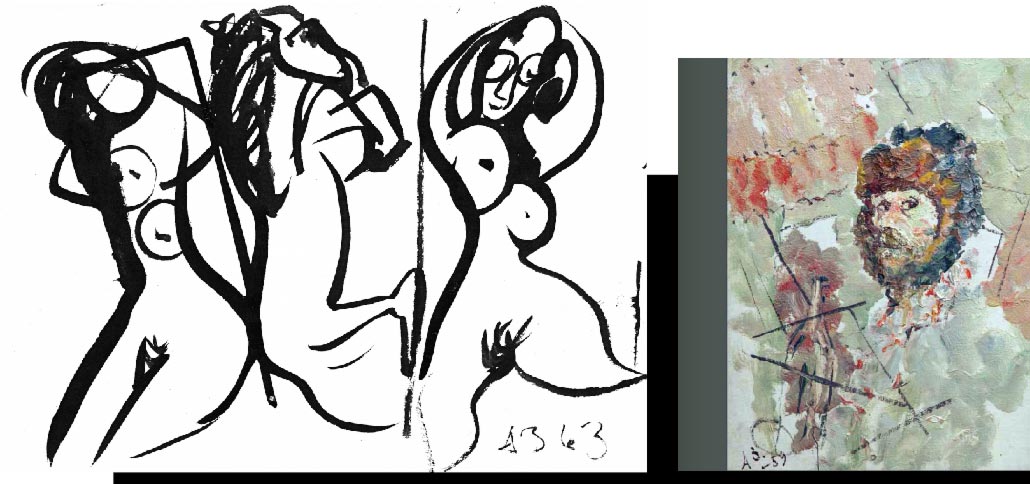

LUCIUS APULEIUS,

«METAMORPHOSES OR THE GOLDEN ASS» Zverev's illustrations to this erotic and mystic work of antiquity that has attracted virtually all 20th-century artists are provocative, elegant, profound and complex. In the comparison with the numerous Metamorphoses of Western modernists, Zverev comes out a clear winner.

|

|

|

|

|

|

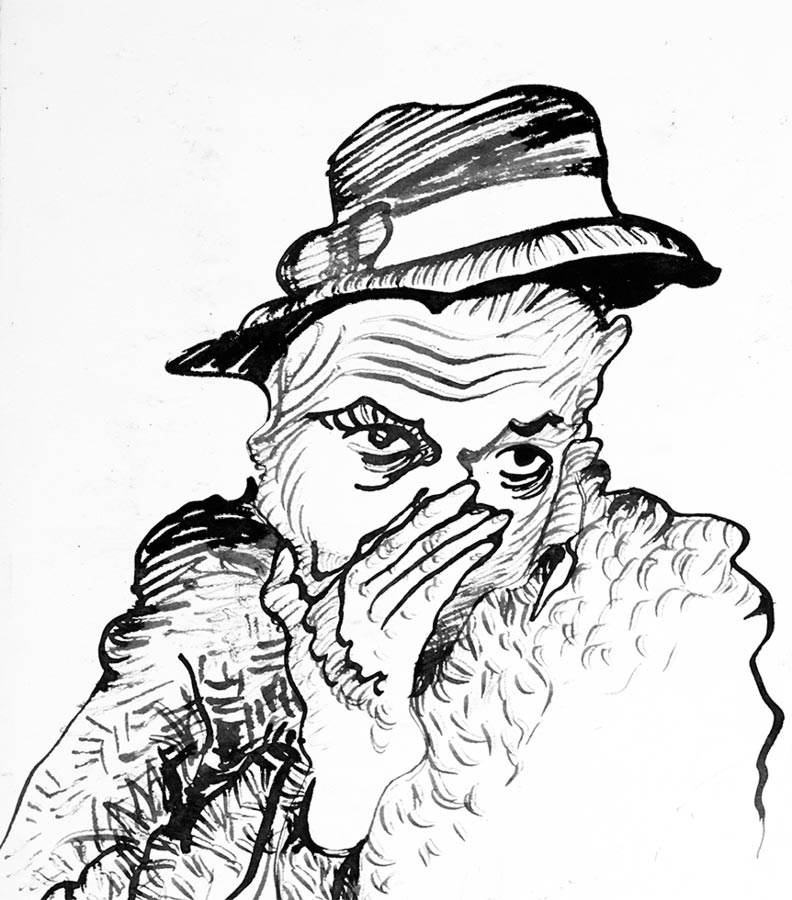

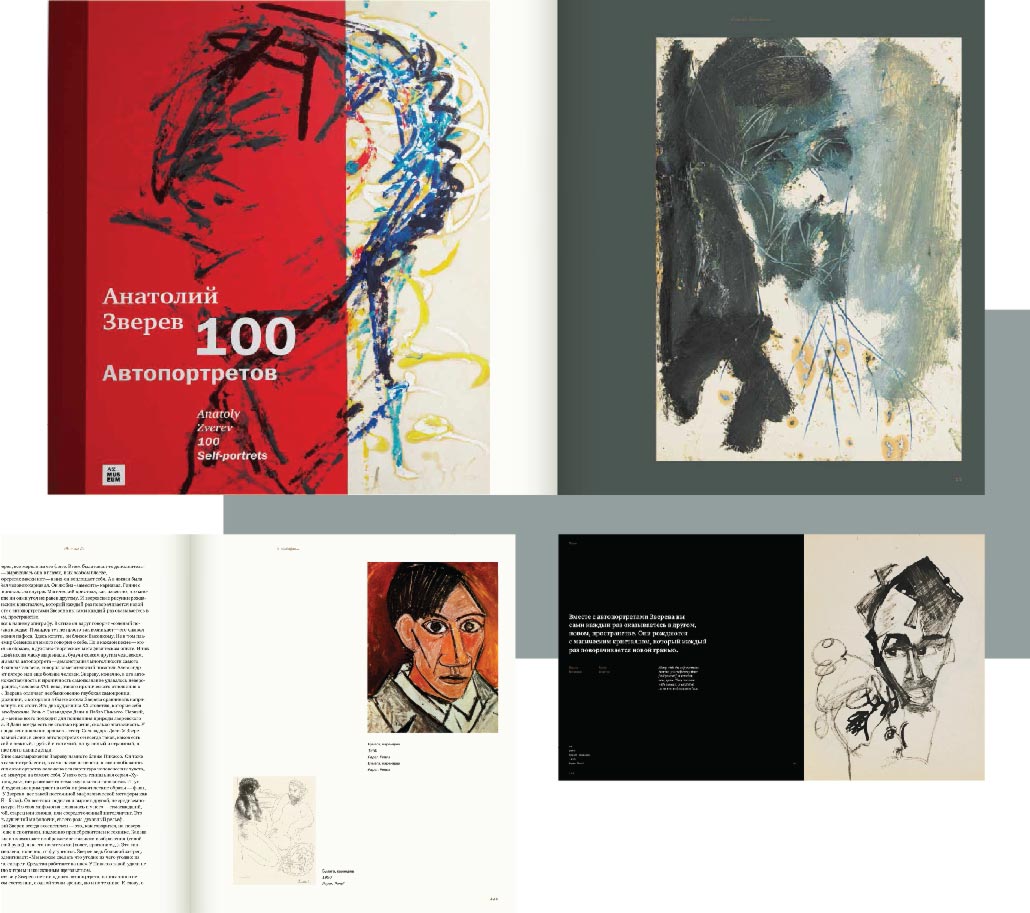

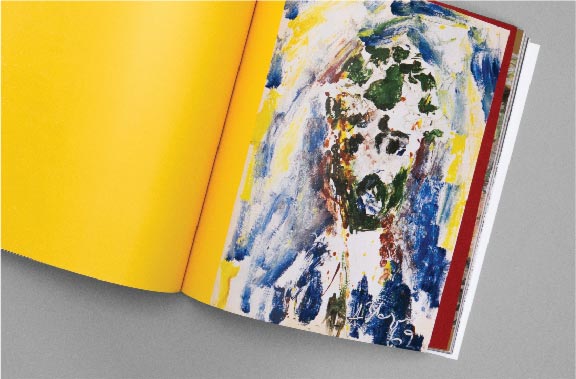

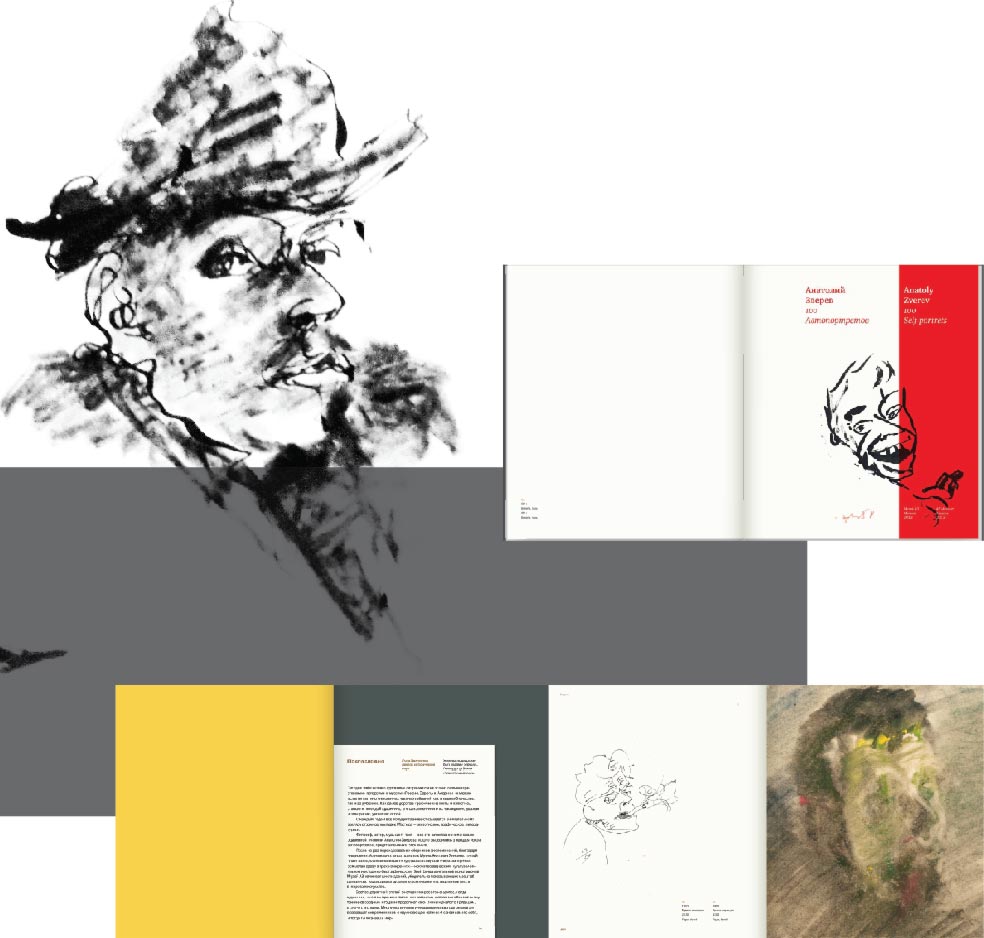

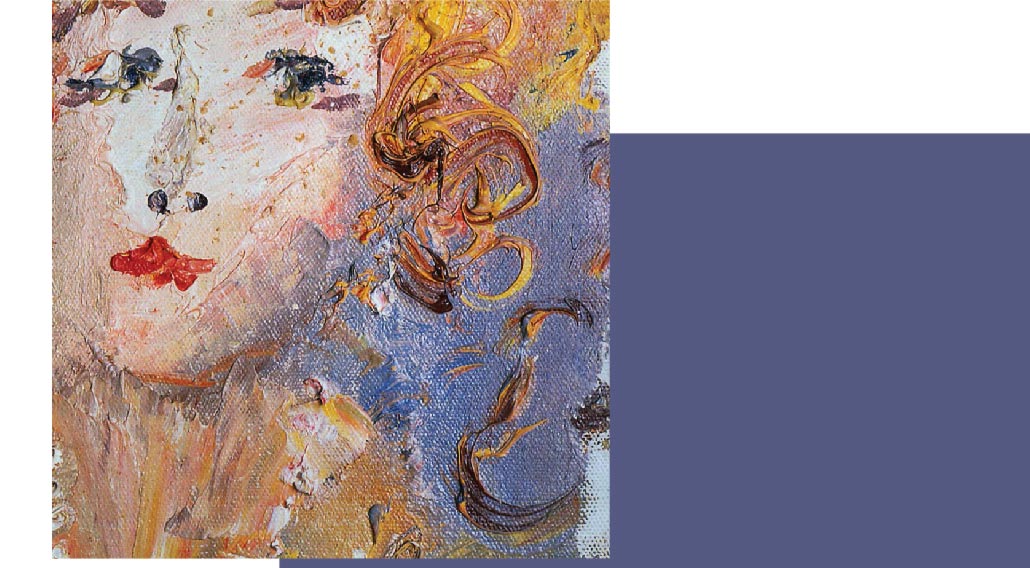

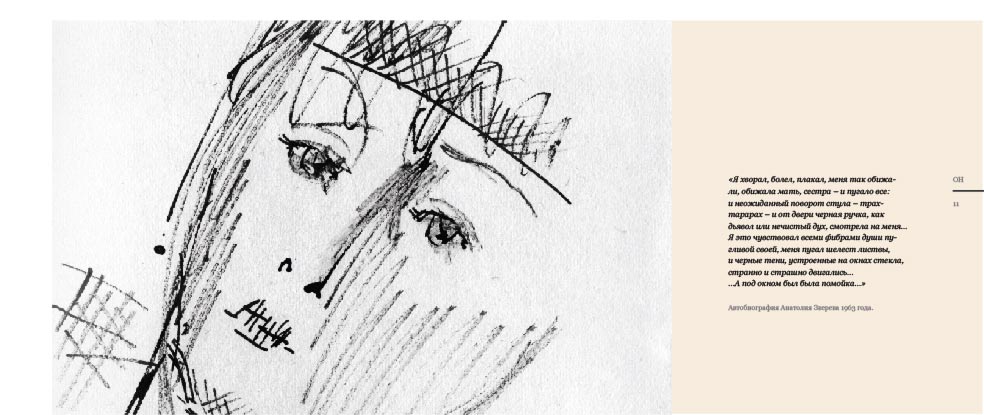

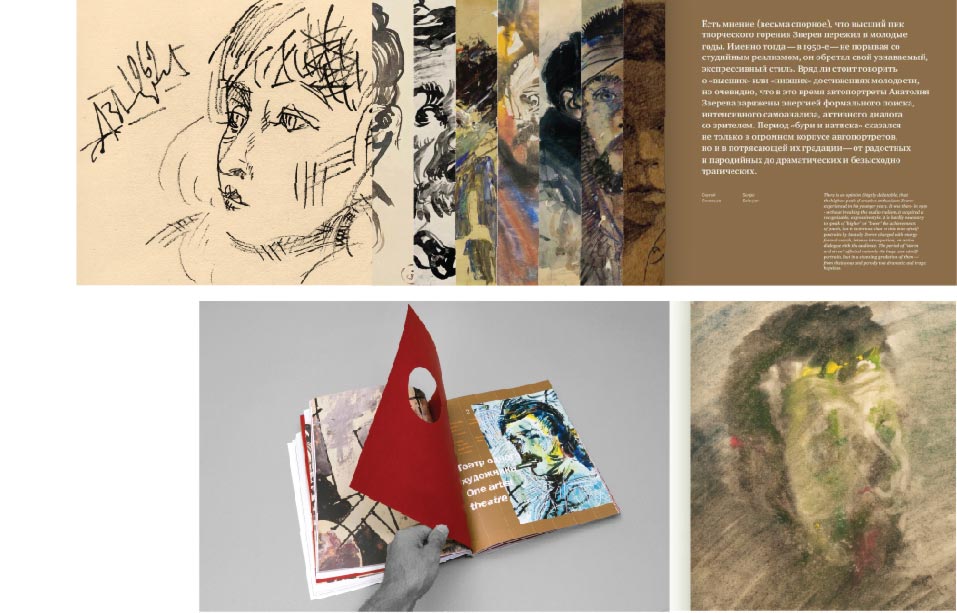

Zverev made thousands of self-portraits over his entire life up until his very last days. Taken together, they constitute the biography and confession of a 20th-century artist that is comparable with the greatest works in this genre by Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

|

|

«ANATOLY ZVEREV: 100 SELF-PORTRAITS»

This exclusive book both in design and in the selection of works (most of which have never been published before) includes everything from quick sketches to programmatic paintings and from "masks" to sublime portrayals and subtle psychological studies. In an article written especially for this book, the cultural scholar Paola Volkova puts Zverev on a par with the great artists that frayed paths in international art towards the self-study of man.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

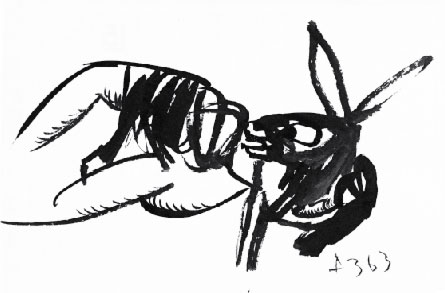

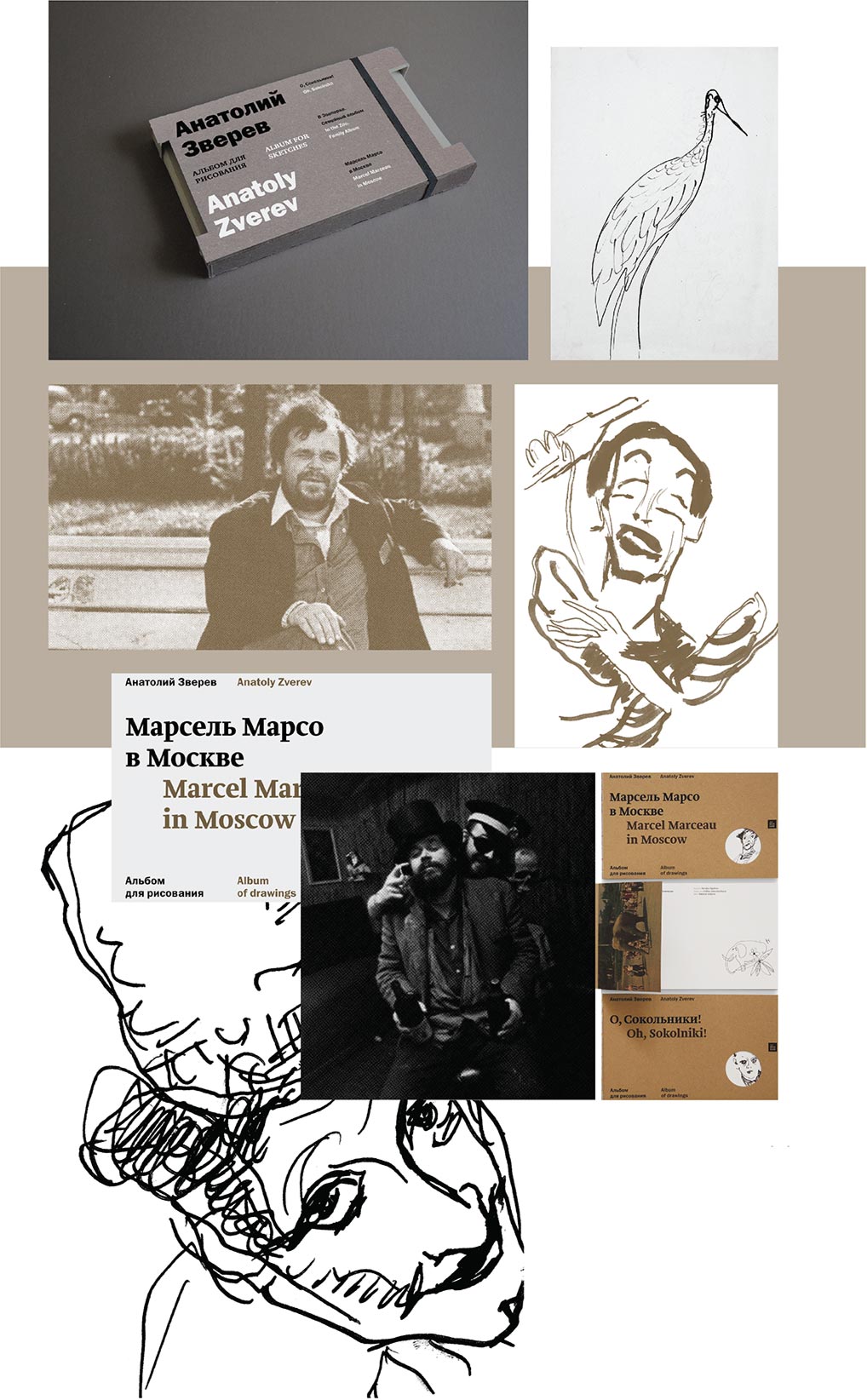

| Genre drawings based on monumental impressions of life in Sokolniki in the 1950s; an extravaganza of sketches made at a performance of the mime Marcel Marceau; and studies of animals and birds that are on par with the "zoos" of old masters.

|

|

«DRAWING BOOKS»

Each sheet by Anatoly Zverev is brilliant and valuable in its own right. However, the artist's drawing books show him improvising and offering increasingly expressive perspectives and images on each new page. They give the feeling of perfection that has always astonished Zverev's viewers.

|

|

|

Shall We

Go to the Zoo?

|

|

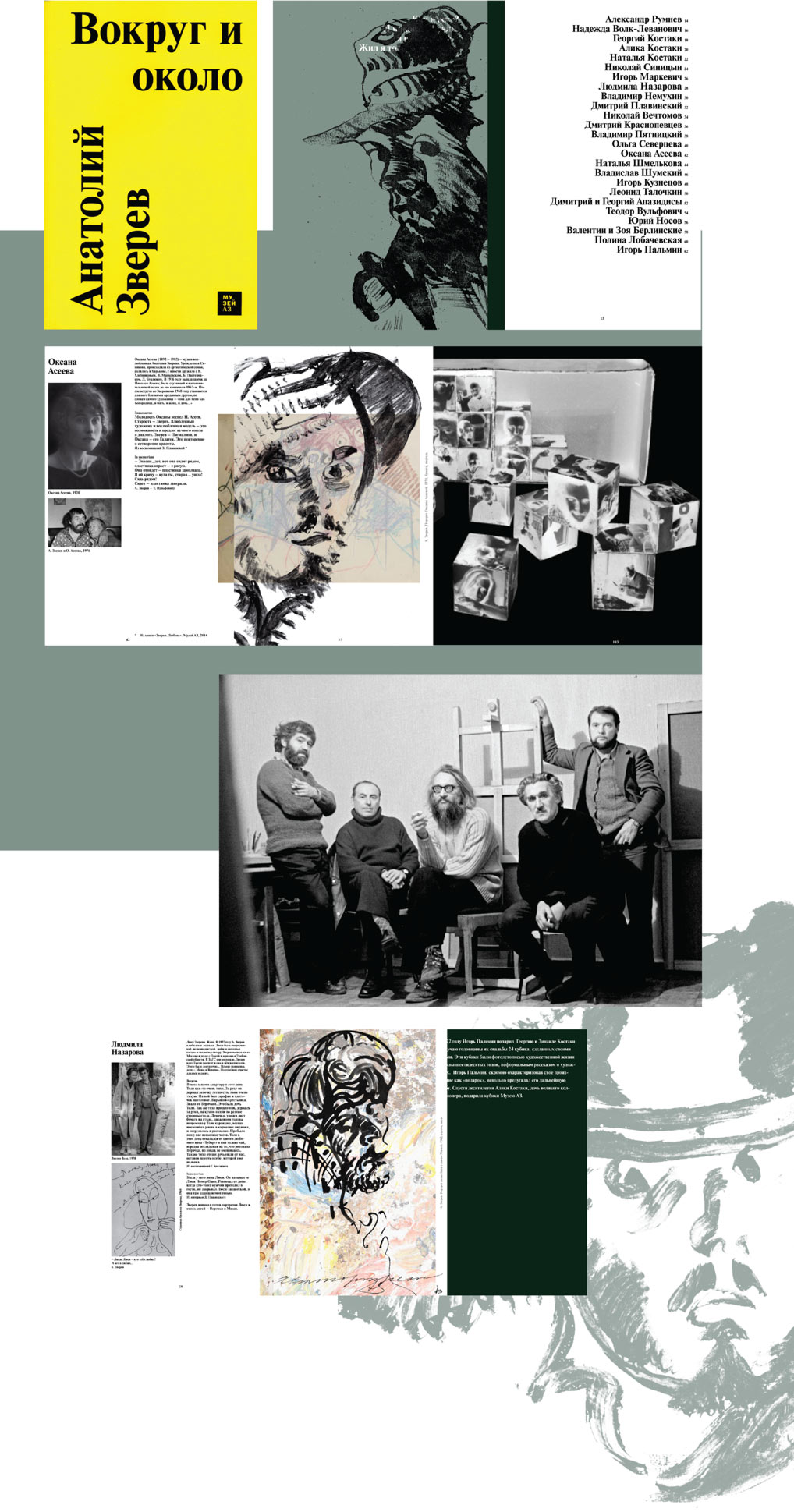

«ROUND & ABOUT»

Anatoly Zverev was more than simply an artist of his time and a member of an artistic movement. Everyone who knew him personally as well as everyone who had seen his paintings or drawings at least once unanimously recognized Zverev to be a unique phenomenon. He was an artist that existed beyond boundaries, styles, movements and conceptions."Art is you yourself!" said Zverev, advocating absolute personal and creative freedom. Dmitry Krasnopevtsev, one of the leaders of non-conformist painting, unequivocally said that Zverev was the most talented artist of all. Round & About is simultaneously a description of Moscow art life in the second half of the 20th century and an illustrated art book. Round & About describes Anatoly Zverev's artistic and human milieu and the best unofficial artists of the time, whom he painted in a gallery of virtuoso portraits. |

|

|

How did I live?

I never lived,

I existed.

I lived only

Among you…

Zverev

|

|

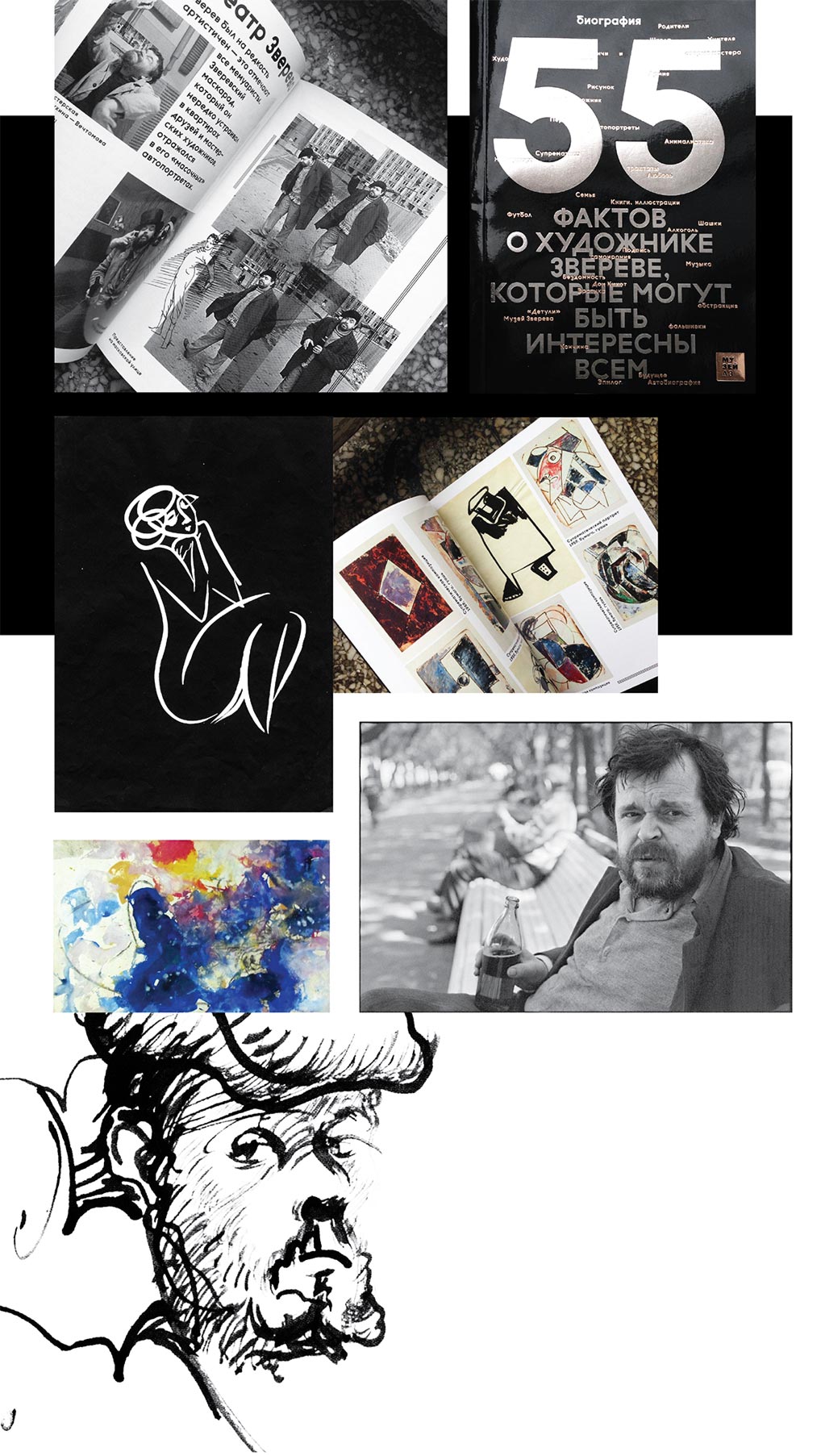

«55 FACTS ABOUT ZVEREV THE ARTIST

THAT WILL INTEREST EVERYONE» Anatoly Zverev's life and work have long become a myth: they are closely connected with his paintings, vagabond lifestyle, and image of a romantic genius. 55 years of his life and 55 facts that are essential to understanding the Zverev phenomenon are described in this new book of the AZ Museum Publishing Project.

Just as an expressive portrait or landscape crystallizes out of an apparent chaos of spots and lines in Zverev's paintings, the image of an artist that overcame earthly gravitation and soared into the future appears out of an unexpected arrangement of "facts" in this book. |

|

|

You can see and hear me in my drawings and paintings!

Zverev

|

|

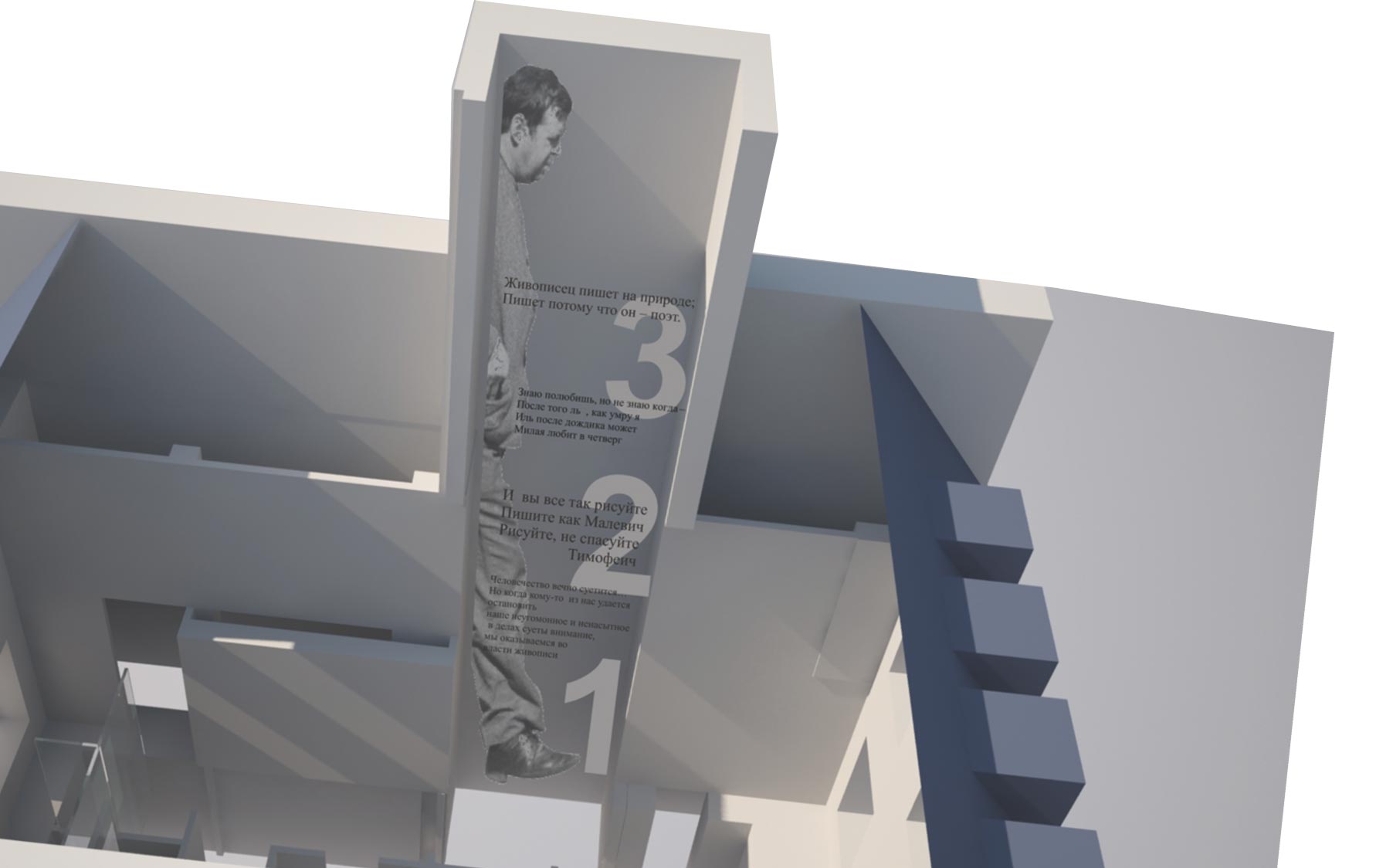

DOCUMENTARY AZ – THAT'S ME!

The AZ Museum has made a film that is dedicated to the opening of the museum and its first exhibit AZ – That's Me! The film tells about Anatoly Zverev's life and presents the exhibit concept: the artist's biography as seen through his self-portraits and the portraits of people that surrounded Zverev during his life. His friends, his beloved, his virtuoso paintings and poems, his paradoxical words and his extravagant behavior are the subject of a vivid and emotional documentary film. The film AZ – That's Me! is the first series in our "art serial" that will document the life of the museum and present Anatoly Zverev's work in all its diversity. The film was written and directed by Zoya Apostolskaya. The text is read by Alexander Filippenko, people's artist of Russia. |

|

|

The fact that every publication by the AZ Museum became a bibliographic rarity almost as soon as it was published (the first print runs were sold out) and got awards (NONFICTION Book Fair, short list of the Zhar Ptitsa Prize) and raving reviews from well-known critics demonstrates that books on Anatoly Zverev are in demand and that the work of this great artist is still topical and timely today. This shows that the AZ Museum Publishing Project should be continued. Zverev seems to give the present-day reader a wink, inviting him to follow him, and takes his famous big step, disappearing behind yet another book cover. Every page shows Zverev's living and changing world, and every book presents a totally new image of the artist. These images are inexhaustible.

|

|

|

|

«Apuleius, The Golden Ass»

«… I could compare Zverev with Picasso. Picasso also illustrated ancient works (Ovid's The Metamorphoses). Nevertheless, if we compare Zverev and Picasso, it'd be safe to say that Zverev is even better than Picasso in some ways. Zverev's lofty place in international book illustration is evident yet has not been described by anyone yet. We should take his book illustrations seriously, as they are an unfamiliar side of Zverev both for specialists and the public at large»

ANDREI SARABYANOV, art critic.

«I have never seen such illustrations to Apuleius. They are wonderful! They are totally devoid of direct eroticism that marks the work of Mir isskustva artists. No, they aren't erotic, and I don't know how Zverev managed it. That's how his hand worked, and it's a real miracle and a real mystery.».

EVGENY SIDOROV, literary critic.

«Anatoly Zverev's Gogol Cycle»

«I love Gogol. And, in the last days, I have also come to love Zverev. This is a wonderful art book that is made in a very high-quality and refined way… The Gogol Cycle is a book of free illustrations. Yet it's not a question of superficial dancing. It's more akin to the state of a person that finds himself in a whirlwind of inspiration. He comes to resemble a strange creature that doesn't have a mind but only eyes, and the world enters him through dilated pupils. Zverev was an explosive and even catastrophic talent.

«Zverev was absolutely equal to the task – in the expression of tormented passion and feeling and beauty. I believe that Zverev took out of his soul the things that oppressed, worried and perhaps frightened him and put them on paper. And he communicated his feelings to us better than any artist that has ever illustrated Gogol.»

IGOR ZOLOTUSSKY, literary critic..

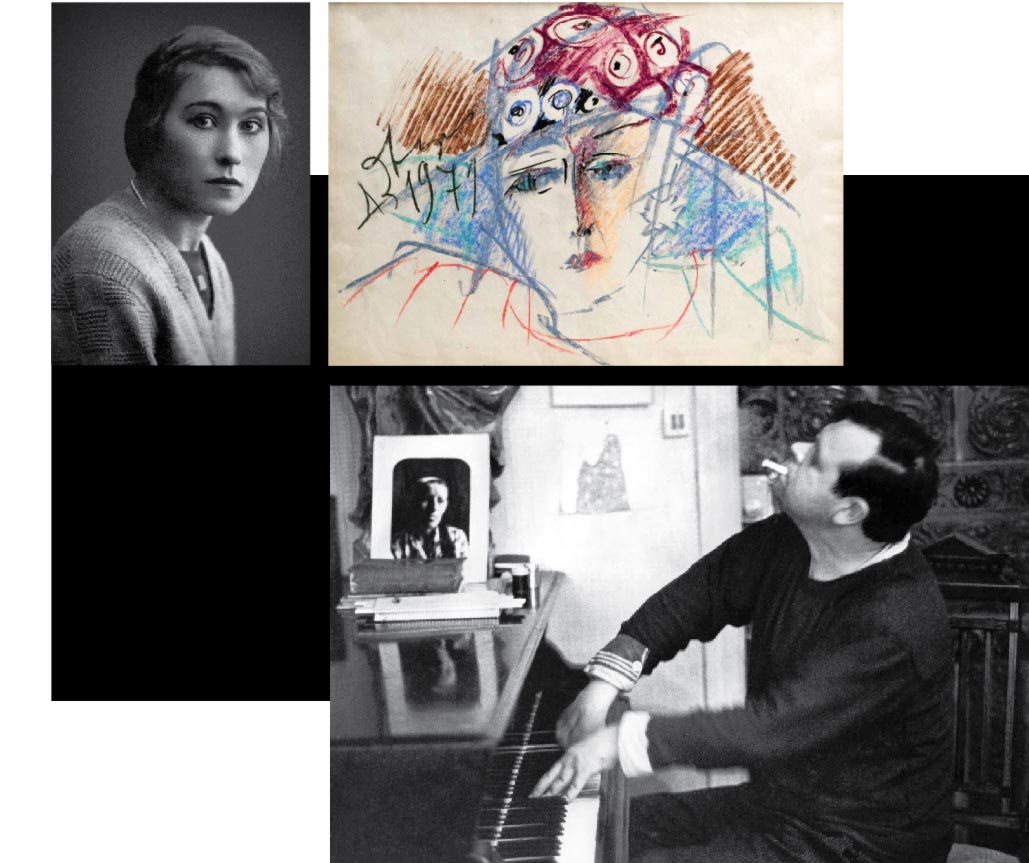

«Zverev in Love»

«The book Zverev in Love is remarkable. The book shall interest readers for all sorts of reasons – first and foremost, on account of the novelty of this love affair. Yet the book describes the latter in such a way that these feelings look pure and transparent, and you don't get the impression that there is something strange about them. You only realize once more that this was true love. The illustrations are wonderful, and I really like the brief commentaries and Zverev's poems and words.

«Thank you for this literary work. This book is valuable in itself as a poem in prose and illustrations.».

LIDIA IOVLEVA, art critic.

«Anatoly Zverev Illustrates Andersen's Fairy Tales»

The book got an award at the NON/FICTION 2013 International Book Fair.

LOLA ZVONAREVA, art critic.

«I managed to show Andersen at the Traugot Readings in Saint Petersburg. Zverev's drawings got lavish praise not only from art critics but also from Alexander Traugot himself, who had made illustrations to Andersen's works all his life. He looked through these books with such delight! We recalled how the young Traugot brought his illustrations to the publishing house, where he got the support of the great book illustrator Lebedev. Zverev had never gotten such support. His wonderful 40 drawings lay in the archives for about 50 years and have been discovered only now.» «100 Self-Portraits»

«This is not a simple book but a work of design where the text interacts with self-portraits. The word, the letter and the phrase are often independent expressive elements in Zverev's works. Here the parts interact with each other. This book is a creative work. I was interested by the fact that Zverev is being revealed for the first time to the public at large. It is impossible to neglect the fact that artist portrayed himself for many years. Is it narcissism? No, it is better described as close attention to what is happening within a person, and it is no accident that the artist chooses this genre of genres: the self-portrait. It is all about focusing on the human dimension. This is why Zverev's self-portraits are so understandable and attractive to contemporary viewers that strive to understand themselves. The genre of the self-portrait has become very popular in modern culture: people photograph themselves and post their photos in social networking services. The new technologies have given people a tool for depicting and recording themselves and the world around them. Zverev already had this instrument back then, yet he did not use it to scan things but to analyze and interpret them from his own perspective.».

ARTYOM GOLENKOV, journalist.

|

|

|

|

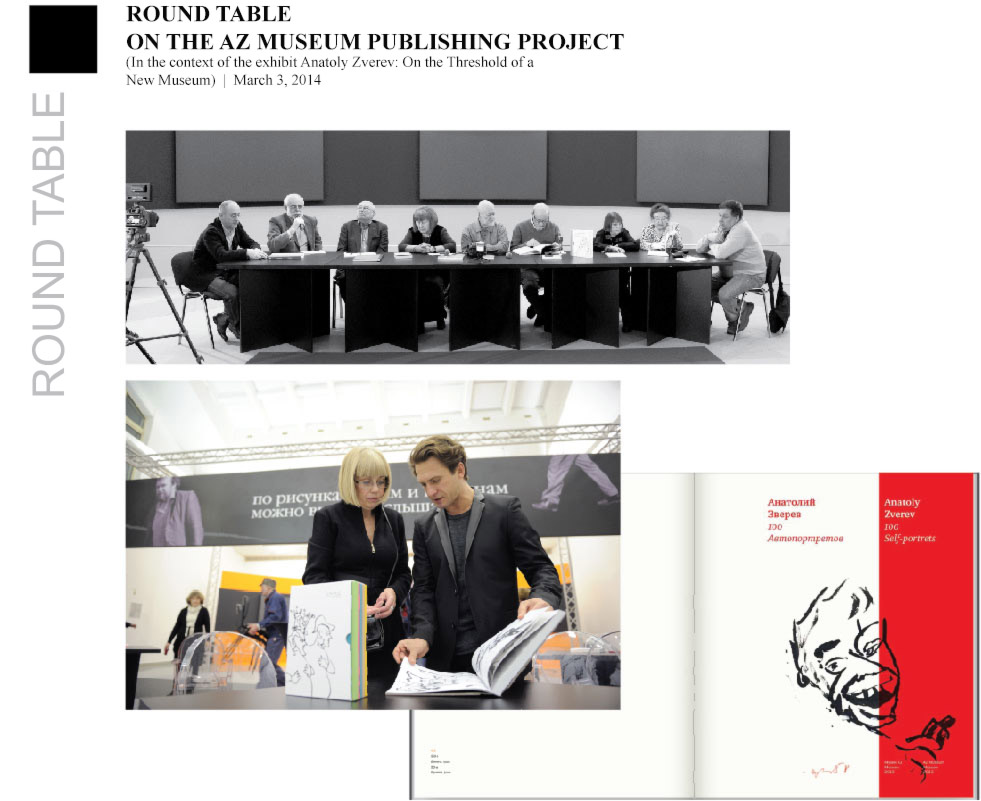

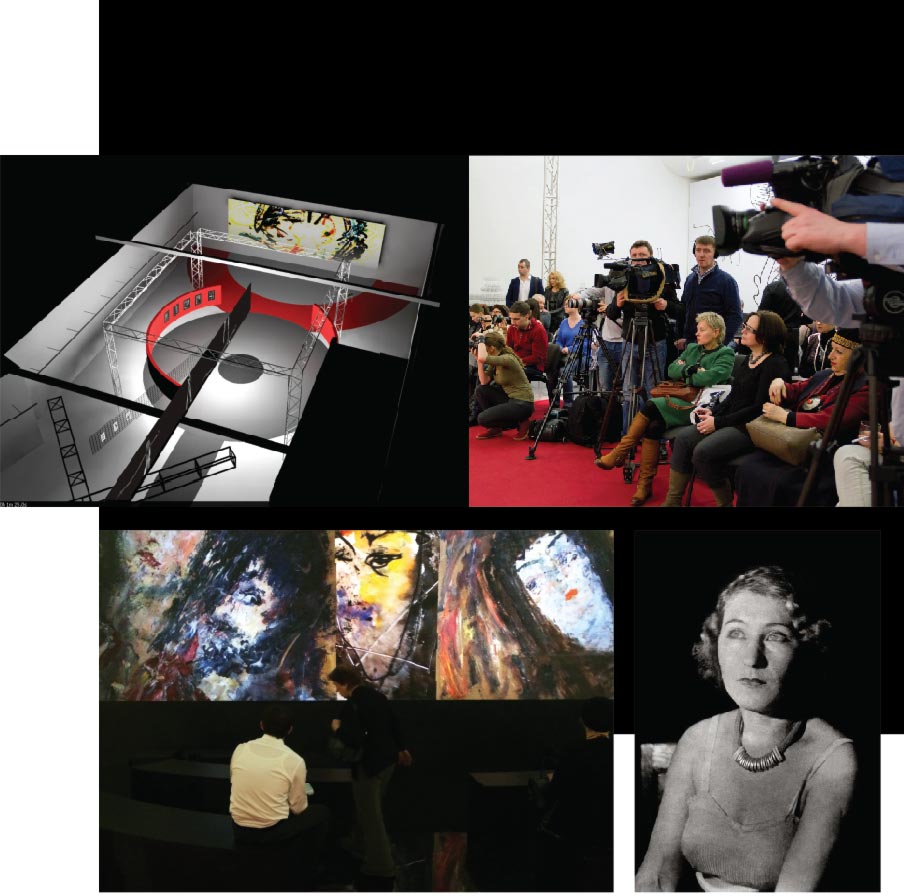

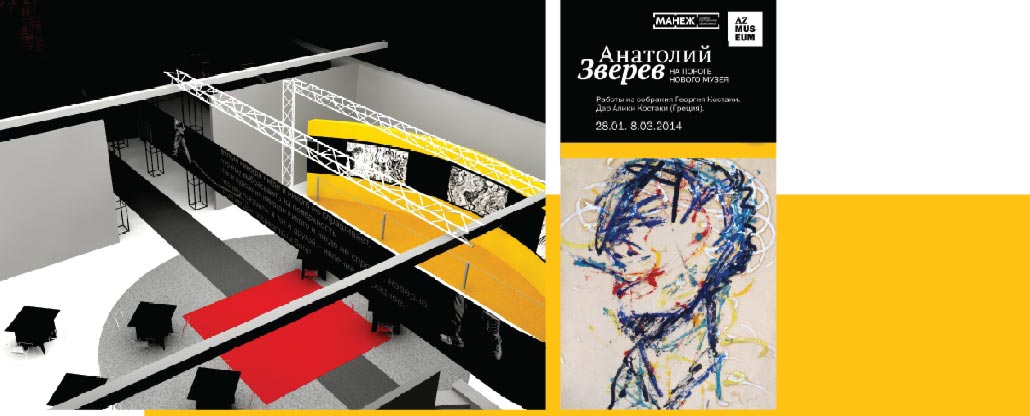

The exhibit On the Threshold of a New Museum presented the conception of the exhibition space of the future AZ Museum as well as acquainting the public at large with remarkable art books and monographs. For a whole year, the AZ Museum Publishing Project has been preparing unique books with Anatoly Zverev's works and his illustrations to world literary classics.

These books became an object of detailed and passionate discussion by art critics, literary critics, writers and publishers.

Round table participants included the leading literary critics Lev Anninsky, Igor Zolotussky and Evgeny Sidorov, the art critics Lola Zvonareva, Mikhail Kamensky, Kira Sapgir, Andrei Sarabyanov, and Lidia Iovleva, the writer Pyotr Aleshkovsky, the journalist Artyom Golenkov, and the art curator Polina Lobachevskaya, author of the Publishing Project. |

|

|

|

Aleshkovsky.

It's wonderful that we are meeting today in the rooms where Anatoly Zverev's exhibit On the Threshold of a New Museum is being held and that we are able to speak simultaneously about the publishing project and its wonderful books and about the exhibit and the paintings that are surrounding us. This exhibit made me take a totally different look at this artist. Zverev's talent was like a volcano that made its genius known everywhere and that recognized itself as such. And I understand that the aim of the people that are so courageously creating the AZ Museum is precisely to show the immense scale of the artist's talent and to bring him into the great pantheon where he deserves to be.

Lobachevskaya.

This exhibit is drawing record crowds – between a thousand and two thousand people a day. A lot of young people are among them. Their reactions are remarkably emotional. This is an unexpected breakthrough in the understanding of the artist. Over 40,000 people have attended the exhibit in less than a month, and over 15,000 people have bought our publications. These are huge figures. One gets the impression that this artist belongs not only to today but also to tomorrow. Regardless of their age and social status, visitors consider him to be a very big artist.

Aleshkovsky.

The exhibit is unique and takes a very modern approach. There are indeed a lot of young people at the exhibit, and this becomes immediately apparent. This is phenomenal. There are a dozen or so works by Anatoly Zverev at the Tretyakov Gallery. Yet this is one of the first times that we have seen an exhibition with such an extensive selection of works, such great expositional culture, such innovative conceptual solutions and such a plethora of technical means.

Kamensky.

Such exhibition rooms represent a totally new approach. This involves not only the work of curators and art critics for the selection of art but also a totally new degree of understanding of Zverev, of how one should approach his work, and how the latter should be displayed to make him regain his proper place both in the history of art and in the public eye. Zverev is the best known painter among the artists of the sixties. Unfortunately, this great renown of his stems not from his true merits but from the vulgar commercial free-market interpretation of him in the nineties. Now that we are embarking on a new cycle, it should be said that it is high time today to strip Zverev's name from all these unnecessary add-ons.

As a cultural institution and a powerful means for promoting Zverev’s work, the new museum shall bridge a gap in our knowledge of the history of contemporary art. The books, too, shall contribute to the future of the museum and of the artist. Anninsky.

Something new and incomprehensible is taking place here now. I'd like to understand what the contemporary viewer gets from Zverev's unpredictable pictures. What makes up their nutritive and satiating essence? I get the impression that today viewers are looking for something that they can't get from rebels or from consumers sprawling in everyday life. What do they see in Zverev's art? If you see a self-portrait next to a portrait, you'll notice that the hero of the latter doesn't look anywhere or doesn't want to look anywhere. As to Zverev, he's always looking at us: we always see his eyes. What do we see in his eyes? I believe that the modern viewer sees the following in his eyes: "Don't rebel, you fool, and don't sprawl in admiration. Be more intelligent that the situation. Fit into the situation, which has existed before you and will continue to exist after you." Zverev himself was able to fit easily into any situation while remaining mysteriously autonomous. Few people are able to do that.

You have to be yourself in all circumstances. People are incorrigible. Fazil Iskander used to say, "You can't make people better – you can only pacify them for some time." I was struck by the self-portrait that Zverev painted two weeks before his death. Someone held a mirror for him, and he painted himself. It expresses both happiness and tragedy. He understood that he would die soon, yet he could speak about it, because he hadn't died yet and shall never die. This quality of Zverev is mysterious and makes him one of the most interesting artists of modernity.

|

|

|

Aleshkovsky.

The new AZ Museum shall also present Zverev as the protagonist of a numerous books and as a remarkable illustrator of great works of literature from Apuleius to Gogol. Here, thanks to the discovered archival materials and the titanic work of the publishers, Zverev appears in a totally new perspective as an intelligent, subtle and profound illustrator. And Zverev is not just an illustrator but sees every author through his own perception of the latter's personality, society and time.

Zolotussky.

Zverev saw Gogol. And Zverev was absolutely equal to the task – in the expression of tormented passion and feeling and beauty.

I believe that Zverev took out of his soul the things that oppressed, worried and perhaps frightened him and put them on paper. And he communicated his feelings to us better than any artist that has ever illustrated Gogol. These illustrations may not entirely match Gogol's plots yet they match Gogol's views about the darkness that exists in the human soul. "Spiritual darkness is frightening," he wrote in his Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends. Gogol chose not to delve into this underworld, yet it frightened and stunned him.

Now that we see Zverev's Gogol cycle, it becomes clear why Zverev approached Gogol: Gogol made it possible for Zverev to express things that he hadn't express in his portraits. In the illustrations, you can see both admiration and terror – terror that is inspired not so much by Gogol as by life itself.

I love Gogol. And, in the last days, I have also come to love Zverev. The Gogol Cycle is a book of free illustrations. Yet it's not a question of superficial dancing. Zverev was an explosive and even catastrophic talent. His illustrations resemble the state of a person that finds himself in a whirlwind of inspiration. He comes to resemble a strange creature that doesn't have a mind but only eyes, and the world enters him through dilated pupils. The book is wonderful insofar as it is interspersed with Gogol's texts. The viewer and reader can read the book twice: read Gogol and then study Zverev's illustrations. It's good that the book highlights the lines that Zverev illustrated. This gives the impression not of a scholarly but of a profoundly human approach to profoundly human artworks. The content and design of these books foreshadow the future Zverev Museum. It shall be an event and an explosion, just like Zverev's talent. Iovleva.

The Gogle Cycle is remarkable, yet the book Zverev in Love is no less so. It shall interest readers for all sorts of reasons – first and foremost, on account of the novelty of this love affair. Yet the book describes the latter in such a way that these feelings look pure and transparent, and you don't get the impression that there is something strange about them. You only realize once more that true love is pure. Anatoly Zverev and Oksana Aseyeva were truly happy, and the book shows how two solitary people got rid of loneliness through this love affair. The illustrations are wonderful, and the dramaturgy of short and pithy commentaries and the arrangement of Zverev's words and poems are remarkably well done. This is not a book but a work of art. A poem in prose and illustrations.

The books issued by the AZ Museum Publishing Project show Zverev from a totally different aspect. I thought that I knew Zverev, yet I never imagined that he is such a serious, deep and independent artist. Now we see that he was not simply a great natural talent and an eccentric but also a very intelligent artist and person. Sidorov.

All the books are published in such a way that you get the impression that you are visiting several different exhibits. Even when Zverev paints with watercolors, gouache, oil or India ink, his works clearly belong in a drawing album. Such a format throws a lot of light on his art.

His book of self-portraits makes a great impression. His numerous female portraits resemble each other, yet, when you look at his self-portraits, you see only the eyes. They are always the same yet reflect totally different states of the world and the person who's looking at you. The self-portraits contain the story of the artist's life and the story of life in general. Zverev's self-portraits are full of sadness and wisdom. Zverev did not belong to any movement. He wanted to live a free life, and he wanted to be free at a time when this was impossible. He was close to the Renaissance in his spirit and in his modernist manner. He tried his hand at everything. For example, he wrote poems to his beloved, yet they were the poems of an artist that assigned a lot of important to color hues and brushstrokes. He also wrote prose and a treatise on art, just like Leonardo. He had great ambitions, although he never liked to speak about them aloud! He wanted to think about the world like Leonardo, and this also creates the impression of a big solitary artist that does not live in a herd and does not attend mass events yet passionately strives to understand the world and his role in it. I had not thought about such things until a few days ago when I first saw these books, these themes and these illustrations. I had never seen such illustrations to Ovid – they are just wonderful! They are totally devoid of the direct eroticism that marks Mir iskusstva art. It's not Somov, but it's not Picasso, either. No, they aren't erotic, and I don't know how Zverev did it. That's how his hand worked, and it's a real miracle and a real mystery. |

|

|

|

Anninsky.

I won't speak about the Gogol Cycle, about Apuleius or about Zverev in Love. I'll only say a few words about the 100 Self-Portraits. I've begun to take a close look at them, and I want to tell you about the feeling that I get from them. Take any portrait – from the early fifties, say – and you'll see that he doesn't look directly at you but averts his eyes. Nevertheless, he crosses your gaze with his eyes under some angle, and you understand that he doesn't simply look you in the eyes but that something has happened and that he has found your eyes. This is true of the early bright and realistic self-portraits. Sometimes, it seems that he's wearing a stylish cap or a crumpled Red Army hat. Yet it makes no difference: it's the voyage of the gaze that spellbinds you. There is a full-length self-portrait with nothing around him. Nothing at all. It makes no difference where you are. It's only the interaction that counts.

I recall how I visited various semi-forbidden ateliers in the sixties. At the semi-prohibited meetings of artists, a countless number of sheets were displayed without hardly any commentaries at all. I stood there and looked as these sheets were laid down. Suddenly, I felt an inner jolt and asked, "What's that?" "Zverev," answered my host without any further remarks. That's how I first heard that name. I've tried hard to recall what I saw on that sheet that struck me so much. It was a black & white drawing, and the relation of lines and spots was so special that it immediately caught your attention. You've got to be a real master to make these things interact on the sheet and give the desired effect. Later, when I saw Zverev's works with color spots, I was struck by how unexpected it was and, at the same time, how natural. How is it possible? You look at a portrait: lines, spots, you can't make anything out, yet you immediately understand where the eyes are. You see the eyes immediately. I began to understand that the eyes are the most important part. Golenkov.

Let me say something about the 100 Self-Portraits, too. This is not a simple book but a work of design where the text interacts with self-portraits. The word, the letter and the phrase are often independent expressive elements in Zverev's works. Here the parts interact with each other, and the book is a creative work. I was interested by the fact that Zverev is being revealed to the public at large for the first time. It's impossible to neglect the fact that the artist portrayed himself for many years. Is it narcissism? No, it is better described as close attention to what is happening within a person, and it's no accident that the artist chooses this genre of genres: the self-portrait. It's not about following a popular fad but about focusing on the human dimension. This is why Zverev's self-portraits are so understandable and attractive to contemporary viewers that strive to understand themselves. The genre of the self-portrait has become very popular in modern culture: people photograph themselves and post their photos in social networking services. The new technologies have given people a tool for depicting and recording themselves and the world around them. Zverev already had this instrument back then, yet he did not use it to scan things but to analyze and interpret them from his own perspective.

Zvonareva.

Without a doubt, young people like Zverev for his freedom and independence. A great event took place in my life after Lidia Kudryavtseva and I wrote a book about Andersen's illustrators – a subject on which we had worked for 14 years. Natalya Opaleva and Polina Lobachevskaya showed us the 40 illustrations that Zverev made to Andersen's fairy tales. The musicality of the lines and the perfection of each drawing were stunning. Nevertheless, the most remarkable thing was that each of the five fairy tales got a distinct Zverev interpretation.

We know that Andersen liked to compare himself with the ugly duckling. Nevertheless, in The Swineherd and The Nightingale, the only positive hero is the nightingale – the symbol of the free and independent artist who sings his song under any circumstances, provided that he is free. We see the love and tenderness with which Zverev drew this nightingale; we see Zverev's vision in this wonderful bird. In The King's New Dress, the crowd is hostile and aggressive. Zverev feels empathy for this king who is being ridiculed and trampled by the crown. For each tale, Zverev drew remarkable cover illustrations. I managed to show these books at the Traugot Readings in Saint Petersburg, where I presented not only the books but also the wonderfully designed publishing program. We can say that the new museum already has a publishing house. These drawings got lavish praise not only from art critics but also from Alexander Traugot himself, who had made illustrations to Andersen's works all his life and to Apuleius, too. Zverev's wonderful 40 drawings lay in the archives for about 50 years. Had it not been for Natalya Volkova, who found them, and Natalya Opaleva, who published them in a refined and brilliant edition, we would have never discovered Zverev's talent as an outstanding book illustrator. This master artist of the 20th century has been published in a worthy format. It is very important for the publishing program to continue: animal drawings, old Moscow and, of course, documentary biography should all appear in the future. |

|

|

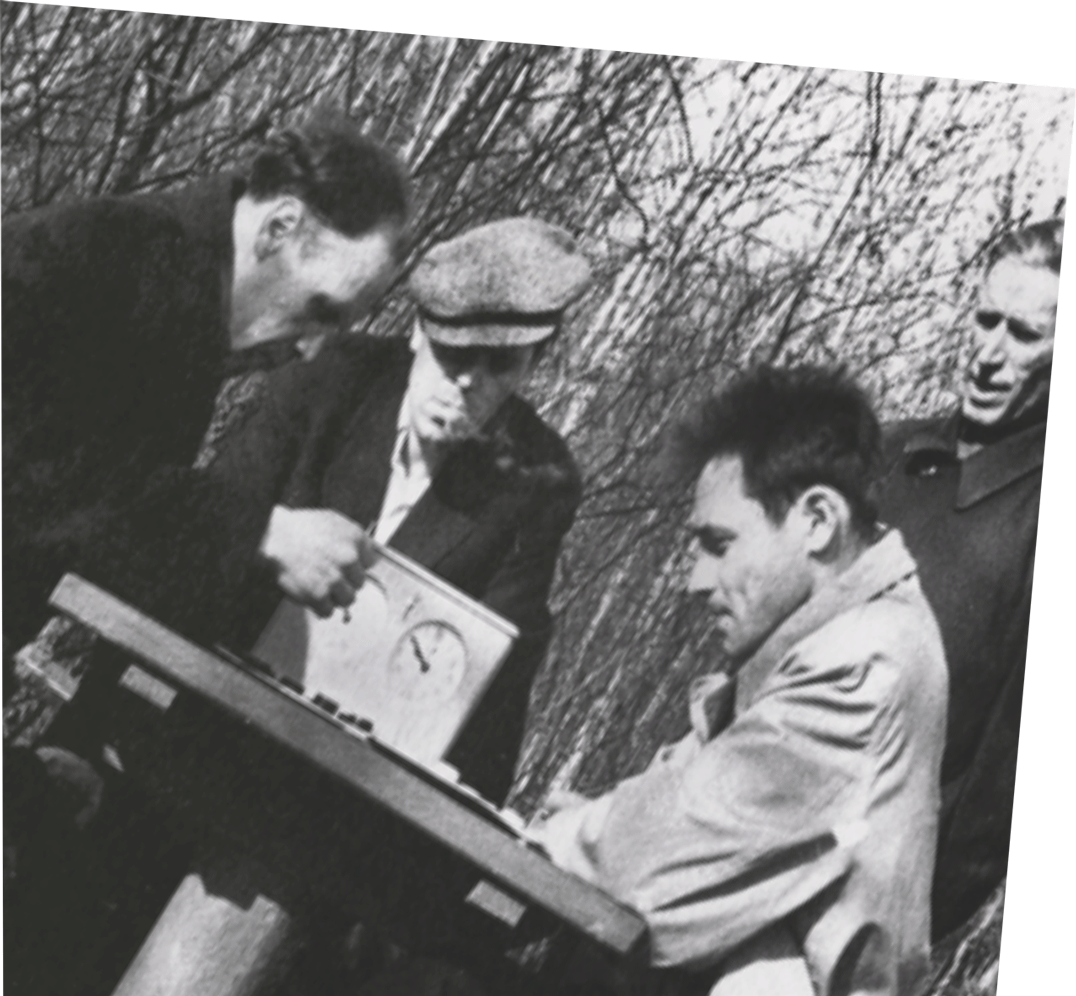

Sapgir.

Today all of us are singing Tolya Zverev's praises. I see Tolya's photographs who's walking here with the black strip in the background, in a pensive mood and with downcast eyes, and I see the self-portraits with the same eyes, except that they're sparkling. It's striking that all his portraits and even his animal drawings show sparkling eyes. You don't get the impression of museum rigidity. Everything is so alive here that I have the sense that Zverev the person has been transformed and that he has stayed and that he is here. This is a museum-person. I recall an exhibit of Dadaists at the Centre Pompidou where these brilliant hooligans were all labeled and classified, and I thought that these subverters would have been dissatisfied with the exhibit. Of course, Zverev was no subverter, and I think that he would have been very happy with this exhibit, because he would have understood that he is present here, too.

Zverev occasionally came over for a visit, and, when he left, his drawings remained. Many of them were masterpieces. I personally saw how he worked on Apuleius and how another world and another myth awoke in this everyday Muscovite. You could always recognize Zverev from a single line of his drawn on a piece of paper. This is the hallmark of a refined artist. We thought that no one would ever understand this. Suddenly, everyone realized that they would be immortalized, and Zverev was the first to be so. Sarabyanov.

Analyzing Zverev's place in Russian and Soviet illustration, I discovered several unexpected things. If we speak about Russian book illustration, we can say that this tradition stems from Mir Iskusstva and that it is realistic (it suffices to recall Dobuzhinsky and Benois). Then this tradition continued into the Soviet period, and there were excellent Soviet illustrators, too (Vereysky, Shmarinov). This line is clear and visible. Yet Zverev clearly does not belong to this tradition.

Thus the only tradition that Zverev is close to and that he continues is the tradition of Russian avant-garde and futurist books. Zverev makes drawings that are totally independent, vivid, artistic, emotional, and free with regard to tradition and with regard to the text. Larionov's drawings to Khlebnikov's texts of 1914 immediately come to mind. As an illustrator, Zverev continues this Russian tradition. On the other hand, I could compare Zverev with Picasso. Picasso also illustrated ancient works. Nevertheless, if we compare Zverev and Picasso, it'd be safe to say that Zverev is even better than Picasso in some ways. Zverev's lofty place in international book illustration is evident yet has not been described by anyone yet. We should take his book illustrations seriously, as they are an unfamiliar side of Zverev both for specialists and the public at large. |